- Home

- TV History

- Network Studios History

- Cameras

- Archives

- Viewseum

- About / Comments

Skip to content

Search Results for: kinescope

April 6, 1948…Oldest Known Howdy Doody Kinescope Footage: Exclusive

On April 6, 2017

- Viewseum

THE ORIGINAL HOWDY PUPPET ON ONE OF THE EARLIEST SHOWS RECORDED!

This kinescope is only 21 minutes long, and most likely was done as a test of the new kinescope system introduced by RCA and Kodak in September 1947. Sometime in April of 1948, the month this was shot, three new RCA TK30 cameras replaced the three big silver RCA A500 Iconoscope cameras in Studio 3H where this was done. This could either be one of the last Iconoscope shows or one of the first Image Orthicon shows. Given the many dub generations this is away from the original, it is hard to tell what cameras may have been in use, but it looks like Iconoscope to me, as the TK30 was more crisp.

The actual date of this show is not known, but is most likely from Tuesday, April 6, 1948, which would be the first Tuesday show after the birth of David Eisenhower on March 31, who’s birth is featured in the newsreel. The baseball score is from a spring training game as the regular season did not start until April 20, 1948.

At this link, you will find the “Early History Of Howdy Doody”, that Burt Dubrow helped me write a couple of years ago, and it is packed with information you will not find anywhere else.

http://eyesofageneration.com/the-early-history-howdy-doody-televisions-first-hit-show/

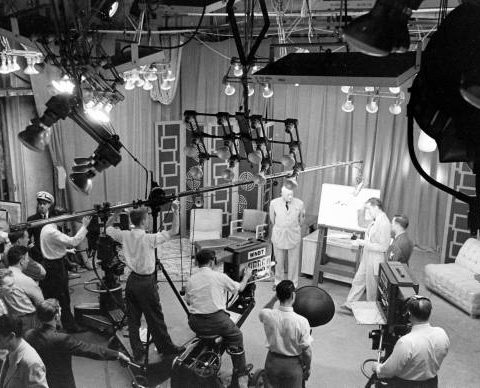

A few notes to help you “see” the history in this. (1) When the show started, it ran only on Saturday afternoon from 5 till 6, but after about 6 weeks, the show began a Tuesday-Thursday-Saturday schedule from 5 till 6. On the 11th show, Howdy announced he was going to run for President of the Kids of the USA. (2) The show was originally called, “Puppet Playhouse” featuring Frank Paris’ “Toby At The Circus” puppet troupe, and on the first show, which Bob Smith was the host and MC for, there was no Howdy puppet, as there was no time to make him, but Howdy was heard! He was in a desk drawer and to bashful to come out.

I mention these points because the first thing I noticed was the opening title is now “Howdy Doody Time”, which is finally proof that the name changed long before many other sources say it did. It probably happened when the show went to 3 days a week, which would be about the second or third week of February 1948…possibly February 10th or 17th. Also, the Howdy for President banner is up. By the way, this would be the first show of the day, as only a test pattern preceded the show, and when it ended at 6, there was not another show until 7:15, so there was another hour and fifteen minuets of test pattern.

When the show starts, notice not only the look of the first Howdy (built by Frank Pairs), but also how different the voice Bob uses for Howdy is. Remember, the voice was developed for the original “Triple B Ranch” radio character named Elmer, who became Howdy Doody after the kids started calling him that because of his greeting of “Well, howdy doody everybody”.

Notice also that the kids are seated in a way that they can only see Bob and Howdy on the monitors, and not at the desk…since Bob was not a ventriloquist, he moved is lips when he voiced Howdy, so it was best to hide that as much as possible. That kind of set up, with his back to the kids when Howdy was talking, continued for the life of the show.

At 13:45, when they go to what would later become the “peanut gallery” the kids are sitting on two, four seat “horses” which were brought over from the place Howdy was born, “The Triple B Ranch” radio show. It was a kids quiz show and the contestants sat on these glorified sawhorses…when one of the kids got a wrong answer, they were “bucked off” the horse.

At 15:03, there is a really special moment! A clown comes in with peanuts for the kids, which seems to catch Bob off guard as he says “Who you?” and then, recovers after a second or two and says thanks “Robbie”. This is most likely the first time assistant stage manager Robert “Bob” Keeshan (Clarabell) had ever worn anything other than street clothes on the set while handing things to Bob Smith. Before the Clarabell costume, it is known that Director Roger Muir had gone to NBC’s wardrobe department for something to dress Keeshan in, and this classic operatic style clown suit was probably their first try.

Many thanks again to Burt Dubrow for letting us see this rare and historic clip from his collection. I hope you enjoyed this very special few moments with the original Howdy on this, the 69th Anniversay of what would later become America’s first daily television program, and the world’s first daily color television program. It was also the first program to log over 1,000 episodes. Since this is the only place to see this video, please share it! -Bobby Ellerbee

NBC Color Kinescopes Continued…Surprises & Rare Footage

On January 15, 2017

- TV History

NBC Color Kinescopes Continued…Surprises & Rare Footage

Yesterday, we discussed the RCA/Eastman Lenticular Color Kinescope process here, and from that we have gained more insight as well as two interesting new color kinescopes.

First, a few surprises. Surprise 1. It seems that one reason there are so few early kinescopes left is because the unions objected to more than one showing of the programs and demanded they be destroyed. The primary opposing force was the Musician’s Union, but others joined in too, claiming that, in an era when there was no such thing as residual payments, it was an unfair financial situation.

Surprise 2. NBC, the major innovator in kinescope use did not object to this…much. Yes, it was an expensive process for them to create and distribute the kines to affiliates not able to get live feeds yet, BUT…by it kept new live programming in demand. Dependency on them for content was important to the bottom line. It also kept the stations without live linkage from turning to outside film sources or local programming.

Surprise 3. It is not a surprise to say that color television was a lot more expensive than black and white, but the lengths to which RCA/NBC went to entice advertisers into becoming color sponsors was. Which helps explain the color kinescopes we are seeing here today.

These two color kinescopes we will see today, were more than likely created as pitch tools for the NBC ad sales department. The same is probably true of the Kovacs color kine we saw yesterday.

To be clear, Kovacs, the Perry Como and Arthur Murray color kinescopes were shot with regular 16mm Eastman color film and not on the lenticular Eastman film. The lenticular color process was used solely for the purpose of time shifting…so that Burbank could record live color feeds from NY, and develop the film in a 3 hour window to air in the west.

Since there was no urgency on the kinescopes made to show (via projector) at client meetings, they were done a different way, but they are indeed color kinescope recordings. Because of the difference in TV’s fields per second and film’s frames per second, only a kinescope camera could shoot this, as opposed to a regular motion picture camera.

Although the Kovacs, Como and Murray shows were live color broadcasts from NY, all three of these were most likely recorded at NBC Burbank on a modified kine machine there. All of these 3 videos fall within the time window that we believe the lenticular color kine system was in use at Burbank.

It is known that Burbank began experimenting with the RCA TRT-1 color video tape machine April 27, 1958 and that the new color capable Ampex VR1000 debuted at the April ’58 NAB convention, which Burbank had shortly after.

What we do not know, and never can know is this…are these recordings shot from the live feed from NY, or are these recordings of the lenticular playbacks on the west coast?

If they are the playbacks, they are not too shabby. If they are images of the live feed, still not too shabby and remind us how great the RCA TK41 was. What do you think?

Enjoy and share! -Bobby Ellerbee

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=DBZgR8DHwM0 Perry Como

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=TGoEXINk76Y Murray/Cooke

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=lEBg6ansaJA Ernie Kovacs

Thanks to Troy Walters in Australia for the Como, Murray clips!

This is an ultra rare colour kinescope recording of the Perry Como Show which aired in living colour on NBC on 12th April 1958. Colour kinescope film recordi…

NBC’s Color Kinescopes…The Lenticular Color Film Process

On January 14, 2017

- TV History

NBC’s Color Kinescopes…The Lenticular Color Film Process

First, this Ernie Kovacs color clip is most likely NOT a lenticular color kinescope, but…it could be, and we will discuss that.

This is a segment from the Ernie Kovacs “Saturday Color Carnival” show dated January 19th, 1957. It was also used in the NBC 50th Anniversay Special in 1976. The “Saturday Color Carnival” shows were all done from NBC’s Colonial Theater in New York.

This Kovacs color film has been widely discussed and displayed as a lenticular kine, but it is a 16mm recording on standard color film of the time. The RCA/Eastman lenticular process used 35mm film, and no lenticular color transfers of any kind are known to exist.

The only way this could be an actual capture of the lenticular system is, if it was a recording of a live playback of the lenticular show for the west coast, or an internal playback sometime afterward.

I have read many discussions on this clip, and several describe this as an NBC color kinescope film made for limited distribution to sponsors with a modified kine, which I think may be right.

It would be a simple process to use a regular kinescope camera (with their special shutter speed needed to record live television), loaded with color film to shoot a 5″ color monitor, instead of the usual B/W monitor. Burbank probably had a modified kine machine like this they used for sponsor requests and also lenticular comparison tests.

That simple process would seem to be an elegant solution to time shifting…that is delaying an east coast live show for rebroadcast in the west, BUT! The problem was that color film could not be processed in the 3 hour window the network had to turn it around, however…black and white film could be. That is where the lenticular process comes in.

On page 40 and at the top of page 41 is a description of how the process worked from the book “Jump Cut” by video editing pioneer Art Schneider.

From the November 17, 1956 issue of “Broadcasting” here is the article on the press demonstration at NBC Burbank.

In the comment section, I have included a couple of images that show close up views of what the lenticular film surface would have looked like.

Unless the NBC engineer who recorded this pops up and let’s us in on how and when this clip was captured, we will never know if this is an off air color film capture of the live feed from New York, or a capture of the west coast lenticular playback. Either way though, this does approximate what a color film image might have looked like on the very few color screens available across the western United States in those days before color videotape, which debuted in October of 1958.

As mentioned, no lenticular color transfers of those early programs are known to exist and any example of the results of the process are presumed to be lost forever. It is possible that one or more of the original 3 strip (R,B,G) masters survived, but so far, none have surfaced.

Eastman’s “Embossed Kine Recording Film, reversal panchromatic black and white” was the special film stock used and it was discontinued in 1958. NBC’s special lenticular kine machines are long gone. -Bobby Ellerbee

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=lEBg6ansaJA

An excerpt of Ernie Kovacs “Silent Show” from 1957. This is a very rare 50s colour kinescope film recording of a colour program using the lenticular process….

The First Kinescope Images…”Colored Television”, 1933

On December 26, 2016

- TV History

The First Kinescope Images…”Colored Television”, 1933

Earlier this week, I posted a story on RCA/NBC’s first TV transmissions from the new Empire State Building tower, and mentioned an interesting side story was to come later…here it is.

RCA/NBC’s 85th floor transmitters in the Empire State Building began experimental television transmissions from there on December 22, 1931. Separate transmitters for visual and aural transmissions were used with the call letters W2XF and W2XK respectively.

These two transmitters were operated concurrently with another NBC television transmitter already located at the New Amsterdam Theater studio on 42nd Street. This earlier station carried the call letters W2XBS (later transferred to the Empire State transmitter) and operated on approximately 2 MHz with 60-line, mechanically scanned picture signals, and received on mechanical scan receivers.

The first experimental transmission from the Empire State Building were 120-line pictures using mechanical scanning of both film and live subjects, BUT…these are believed to be the first high-power, high-frequency transmissions received and monitored by means of the kinescope, or cathode-ray picture tube.

At that time, the tubes had green fluorescent screens, since the white phosphor later used for black-and-white television had not yet been developed. The Empire State tests, even though at a line rate twice that of the W2XBS 60-line tests indicated that greater resolution would be required for a satisfactory public television service.

“It’s Not Easy Being Green” -Kermit

The CRT’s back then used the P1 phosphor as oscilloscope CRT’s did. Once they started using the P4 phosphor which was a silvery/white, the entire look changed, but the process for making P4 phosphor was not developed until a few years later.

The CRT numbers showed the type of phosphor used in each, for example…a common 21 inch monochrome CRT with the number 21FBP4 used the silver phosphor (P4). A common oscilloscope CRT was a 5UP1 (using the P1 phosphor…green). P22 was used in color CRT’s, for example a common color CRT was a 21FJP22. The last 2 to 3 digits indicated the type phosphor. P3 Phosphor was orange and P7 with a blue glow was used for radar. -Bobby Ellerbee

Vladimir Zworykin: The Iconoscope and the Kinescope

On December 20, 2016

- TV History

December 20,1938…Vladimir Zworykin Patented The Iconoscope

Although there was controversy over a lot of patents and inventions in electronic television between Philo Farnsworth and Zworykin and RCA, there is no contention over the development of the Iconoscope.

While working as an engineer at Westinghouse in 1923, Zworykin had presented his idea to the company, but they were not interested. That year he submitted his patent, but because the design was incomplete, the patent was not approved. By 1933 he had achieved a working model and with more modifications to his application in 1935, the patent was finally granted in 1938.

At the 1936 Berlin Olympic games, Telefunken’s two cameras were using the Iconoscope, and the single Fernseh camera there was using the Image Dissector from Farnsworth.

Vladimir Zworykin may not have liked modern TV programming, but he can be proud of the remarkable system that he helped create. It truly changed the world!! Learn more about it here!

1948: NBC Puts Kinescopes In Use

On September 15, 2016

- Archives

NBC announces the first use of kinescoped recording on its network, June 27, 1948.

1949: First West-East Kinescope

On September 15, 2016

- Archives

A 1949 NBC press release notes the first transmission of a West Coast kinescope to the East Coast.

September 13, 1947…The RCA Kinescope Machine Debuts

On September 13, 2016

- TV History

September 13, 1947…The RCA Kinescope Machine Debuts

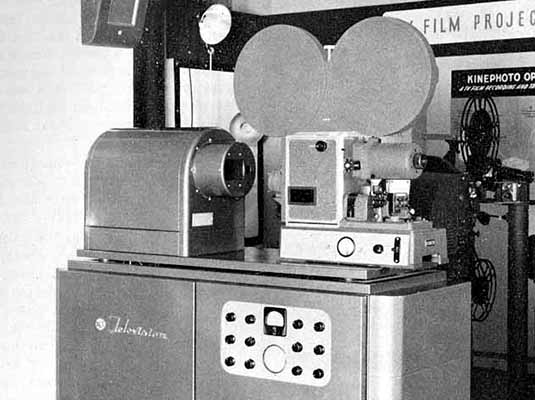

In association with Dumont, Kodak and RCA announced the developed a special film camera to shoot directly off a TV screen. This was the first “time shifting” technology to come to television. Nine years later, video tape would become the second.

Officially titled, the “Eastman Kodak Television Recording Camera”, a Kinescope recorder was basically a special 16mm film camera mounted in a large box aimed at a high quality monochrome video monitor. All things considered the Kinescope made high quality, and respectable TV recordings.

The Kinescope was quite the clever device. It’s film camera ran at a speed of 24 fps. Because the TV image repeated at 60 fields interlaced (30 fps) the film had to move intermittently between video frames and then be rock steady during exposure.

The pull-down period for the film frame was during the vertical interval of less than 2 mili seconds, which was something no mechanical contraption could do at the time.

Together, Dumont, RCA and Eastman Kodak found various ways around the problem by creating a novel shutter system that used an extra six frames of the 30 frame video signal to move the film. This action integrated the video half-images into what seemed like smooth 24 fps film pictures.

Of course, the kines were played back on air using film chains running at 24 fps, so the conversion to film was complete and seamless. Until videotape recorders made their debut, the Kinescope was the only way to transmit delayed television programs that were produced live.

June 21, 1948…First TV Network Pool Event & Debut Of RCA Kinescope

On June 21, 2016

- TV History

June 21, 1948…First TV Network Pool Event & Debut Of RCA Kinescope

The first official use of kinescope recording would come on June 21 at the Republican National Convention in Philadelphia, but it was not used in the way we generally think of kinescopes, which is recording programs to film and expressing them to affiliates not able to connect to the network live. Here’s the story…

This event was also the first ever pooling of equipment, and lines by the television networks including NBC, CBS, Dumont and ABC.

There were four pool cameras (RCA TK30s) in the hall, and one at a quieter spot for representatives from each network to do a 15 minute per hour commentary. The 4 hall cameras were on the main line out, and the single commentary camera was on a second line out. Only NBC had the ability to record their commentary and insert it at a more opportune time, rather than interrupt a major speech on the floor, when their 15 minute live slot came up.

All together, the pooled convention coverage was shown live on 18 stations in 9 cities, which included New York, New Haven, Newark (ABC), Boston, Albany-Schenectady, Baltimore, Washington and Richmond.

In July, The Democratic National Convention was held at the same arena, and the same pooling process was used by the networks again. At this link is Harry Truman’s acceptance speech, and as you can tell by the haloing on the mikes, this is a recorded video signal, and not film, so you can see how good the results were on this kinescope from NBC.

NBC Chief Engineer O. B. Hanson said in the June 17 press release (included below), that the system had been used for testing a few weeks before this. At the link, is perhaps the first kinescope recording of a major NBC program…”Puppet Playhouse”, with Howdy Doody, from July 2, 1948. However, I have seen private Doody kinescopes from as early at February of 1948, so I know they were testing much earlier.

NBC’s engineering department was quite busy that spring of 1948. They debuted not only the new Studio 6B (for television), but that same night, debuted “The Texaco Star Theater” there on June 8, 1948.

Just months before, NBC Television added Studio 8G, 3A and 3B, and around May of ’48, converted Studio 3H (Howdy Doody) from Iconoscope cameras to TK30 Image Orthicon cameras. All the while, preparations were being made for the Republican National Convention which was a historic first for television all around, with over one million viewers watching on the biggest nights of the convention on about 340,000 sets in those 9 cities. TV set manufacturers had ramped up production in the two months before the June convention to 45,000 a month and never backed off to a lesser volume. TV was on it’s way! Enjoy and share! -Bobby Ellerbee

Via Kinescope…A Trip Back To April 1956 With Milton Berle

On April 21, 2016

- TV History

Via Kinescope…A Trip Back To April 1956 With Milton Berle

Above, we go to the live “Milton Berle Show”, from the USS Hancock in San Diego. Here’s the whole show with Elvis Presley debting “Blue Suede Shoes”, Esther Williams, Harry James and Buddy Rich filling out the bill, with Arnold Stang joining Milton for bit.

This was a color presentation, and that is why the kinescope looks a bit soft. The first five minutes of this are really fun and the Elvis intro comes around the 17 minute mark. After “Heartbreak Hotel” and “Blue Suede Shoes”, Milton becomes Presley’s twin brother, Melvin and possibly sets the stage for The Who’s, Pete Townsend by smashing his guitar. -Bobby Ellerbee

A Brief History Of The Kinescope…Historic Images & The Machine

On April 21, 2016

- TV History, Viewseum

A Brief History Of The Kinescope…Historic Images & The Machine

The first official use of the RCA Kinescope process was the week of June 21, 1948, at the Republican National Convention in Philadelphia. NBC affiliates not connected via coaxial cable or microwave would would receive the film, the next day via Rail Express.

As you will see in this video from NBC’s KNBH in Hollywood, testing had been done as early as 1938. I think this report was probably done in early 1949.

Also seen here, the kine recordings of the first broadcast using the RCA TK30 Image Orthicon cameras in June, 1946 at the Joe Lewis – Billy Conn rematch at Yankee Stadium. Near the end, we’ll get a look at RCA’s latest Kine in action. Videotape couldn’t come soon enough. – Bobby Ellerbee

By Request…Historic Kinescope Footage & The Machine Itself

On January 24, 2015

- TV History

By Request…Historic Kinescope Footage & The Machine Itself

Several people asked to see more on the kinescope process, so here from NBC’s KNBH in Hollywood, is a look at some early kine images starting with some of the first Iconoscope images from 1938. I think this report was probably done in early 1949.

Also seen here, the kine recordings of the first broadcast using the RCA TK30 Image Orthicon cameras in June of 1946 at the Joe Lewis – Billy Conn rematch at Yankee Stadium. Near the end, we’ll get a look at RCA’s latest Kine in action. Videotape couldn’t come soon enough. Enjoy and share! – Bobby Ellerbee

https://www.youtube.com/watch?feature=player_embedded&v=0HbODxTSDmM

‘Peter Pan’…ULTRA RARE! Two 1955 & One ’56 Kinescope Scenes!

On November 11, 2014

- TV History

‘Peter Pan’…ULTRA RARE! Two 1955 & One ’56 Kinescope Scenes!

Make sure you open this article to see it all and the links to all three clips! I didn’t know any parts survived till now, so this was a big surprise and a real treat!

On March 7, 1955, NBC did the first live broadcast of ‘Peter Pan’ in a ‘Producer’s Showcase’ color special from NBC Brooklyn. It was such a hit that they did it again live on January 9, 1956. Like the first, it too was in color from Brooklyn with the entire Broadway cast returning for the television adaptation, starring Mary Martin as Peter Pan, Cyril Richard as Captain Hook and Sondra Lee as the incongruously blonde Indian princess Tiger Lily.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=wb66Sw0C9Ss

This is the first of two rare clips and is the closing scene of the original 1955 broadcast. This has part of “I’m Flying” and Mary Martin’s closing tag and the credits, which you can barely see.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=s_UV1CA5FUU

This is the 1955 production with Sondra Lee as the indian princes in the “Ugg-a-Wugg” number.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=_i5jzQDyXLI

This is the 1956 show open, cast credits and VO and also shows us the ending with the entire “I’m Flying” scene.

This was done in both studios…I and II (this is the way NBC memos always referred to them, not at 1 and 2, but I and II). I was the larger studio with 11,000 square feet, but it only had a 24 foot clearance from the floor to the grid. Studio II was the taller and had a 39 foot clearance and 9,700 square feet. I think the “I’m Flying” bedroom scenes were all (’55, ’56 and ”60) done in Studio II with it’s higher clearance. Enjoy and SHARE! -Bobby Ellerbee

Peter Pan – Mary’s “Thank You” Tag

This clip is a kinescope of the last few minutes of the LIVE broadcast from 1955, with an “enhancement” created by me!

In Case You Missed It…Color Video Tape Comparison To Kinescope

On September 28, 2014

- TV History

In Case You Missed It…Color Video Tape Comparison To Kinescope

Obviously color makes a big difference, but so does the quality of videotape over kine. This is the “laughing cameraman” sketch that I posted yesterday in a side by side comparison with some neat special effects inserts.

Thanks to Joao Antônio Franz dos Santos for sharing this, but most importantly, thanks to David Crosthwait at DC Video in Los Angeles for making this after transferring the show from a 2″ quad, low band videotape to a digital format for the Lewis family archives. Enjoy and share! -Bobby Ellerbee

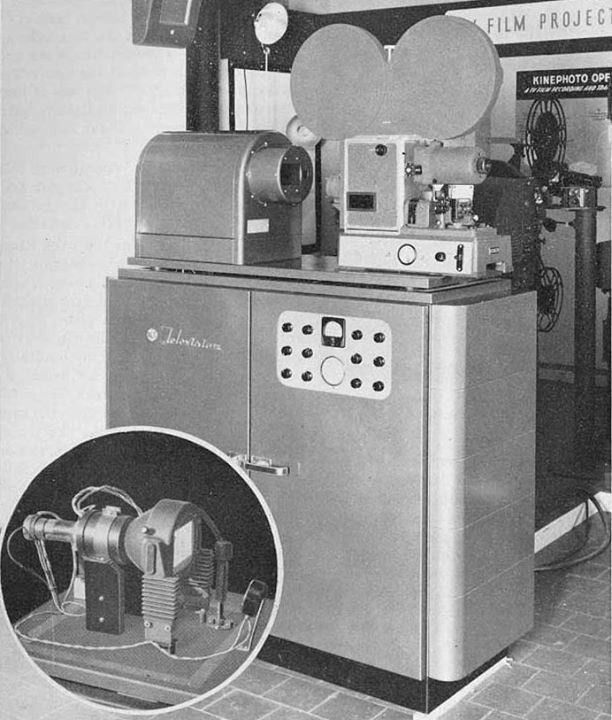

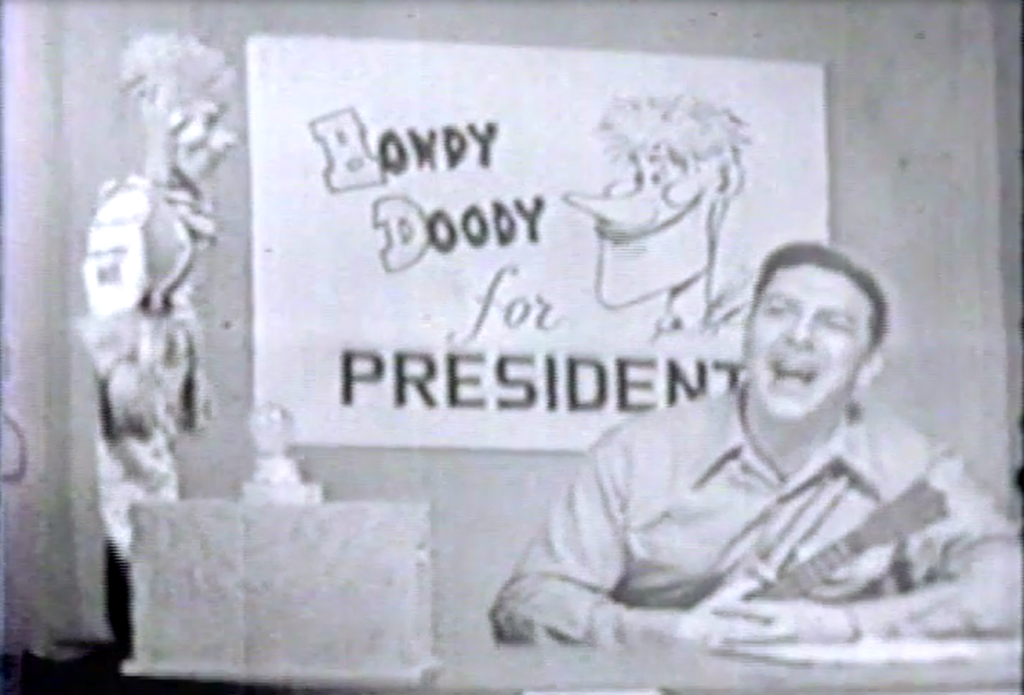

Dumont Kinescope Machines

On September 26, 2014

- TV History

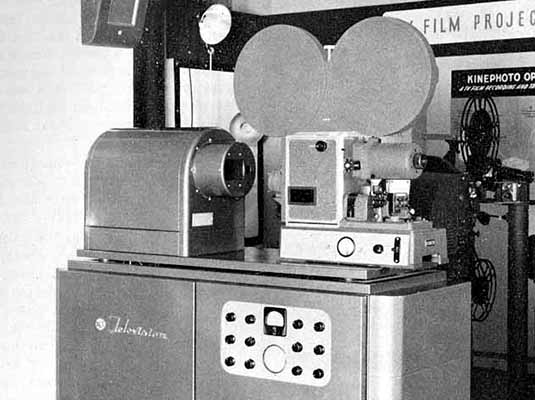

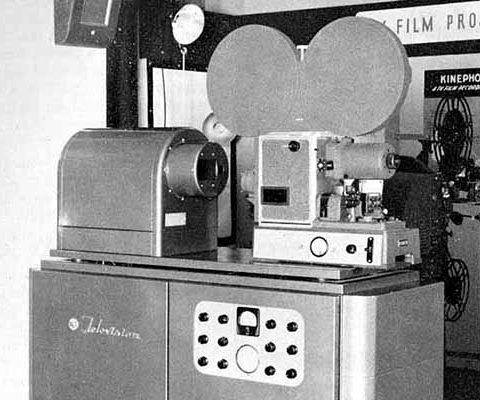

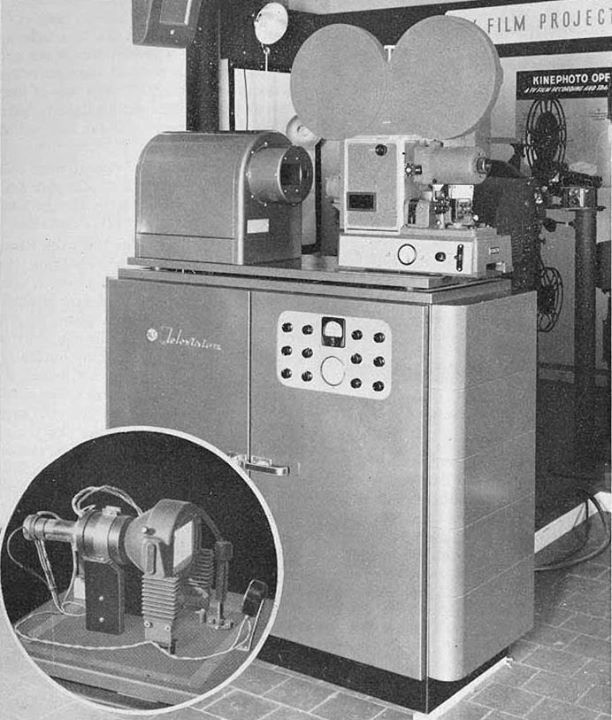

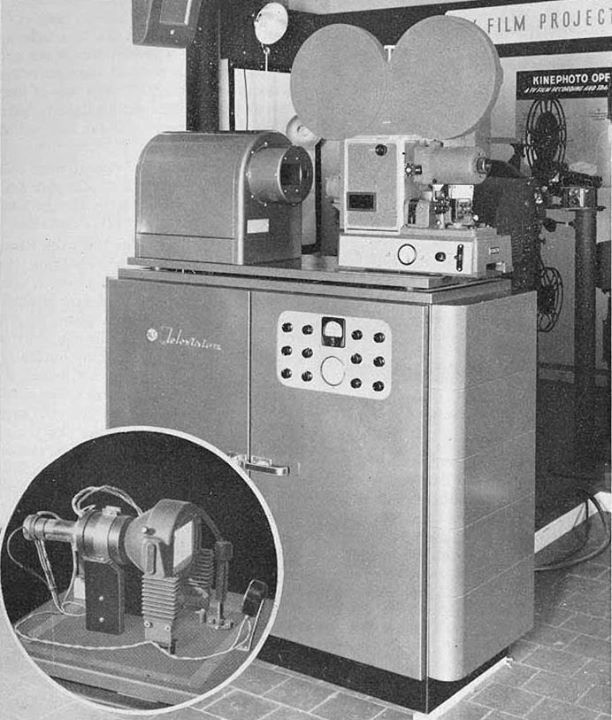

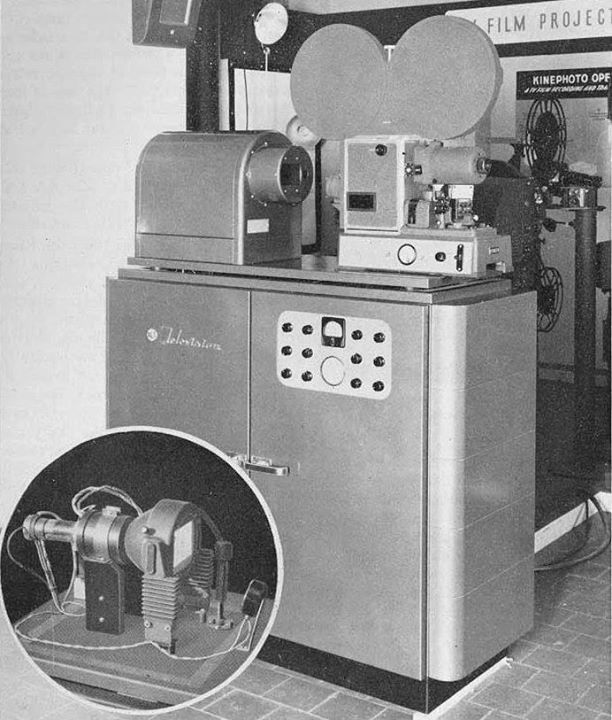

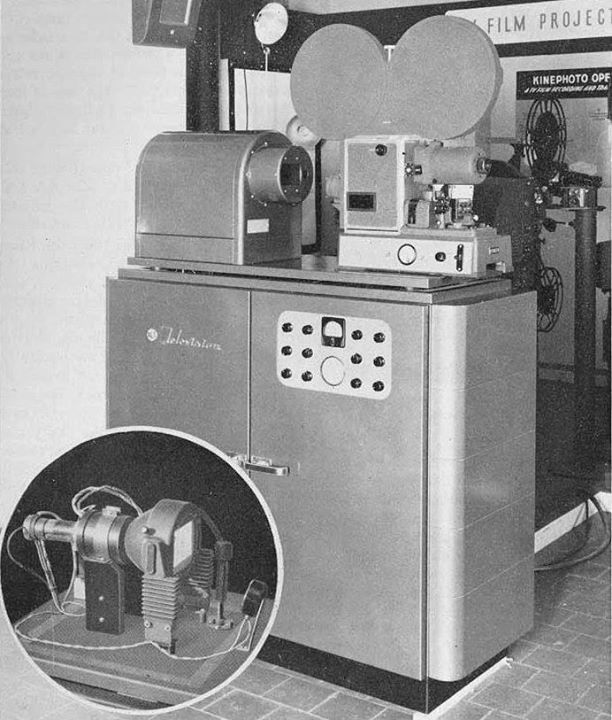

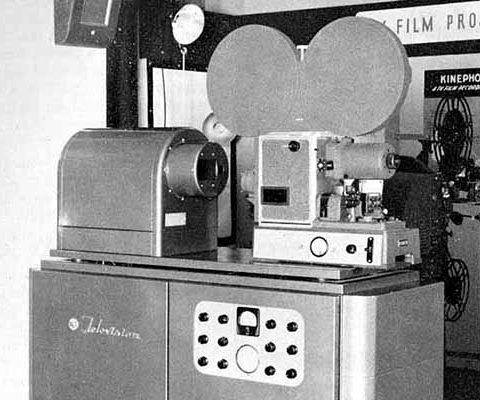

Dumont Kinescope Machines: Quite a rare photo

Before there was video tape, tele transcription was done via the kinescope process. Inside the cabinet, behind the panel door there is a cathode ray, or picture tube pointing up so the image can be seen via the mirror box. The image is then recorded by a small film camera as seen here with the film magazine above it. The operator can adjust the picture quality and audio with the oscilloscope and control panels shown here.

From Kinescopes to Digital Cinema

On September 15, 2014

- TV History

The Latest Article From Richard Wirth…”From Kinescopes To Digital”

Television’s main technical challenge has always been, how to deliver the best image. That has not been easy given the need for time delays in the broadcast world and in this article, Richard does a fine job of bringing us through the many steps that have lead us to where we are now. Enjoy and share! -Bobby Ellerbee

http://provideocoalition.com/pvcexclusive/story/from-kinescopes-to-digital-cinema

From Kinescopes to Digital Cinema

Last time, we charted early efforts to project TV signals on theater screens. This time, we look at the camera side – electronic acquisition. In the end, digital firsts in BOTH projection and acquisition came down to one movie in a place nowhere near Hollywood. But I’m getting ahead…

NBC Introduces Kinescope Recording…June 1948 Press Release

On March 25, 2014

- TV History

NBC Introduces Kinescope Recording…June 1948 Press Release

The Kinescope dominated TV recording for time delay in the early 1950’s. A Kinescope recorder was basically a special 16mm or 35mm film camera mounted in a large box aimed at a high quality monochrome video CRT. All things considered the Kinescope made high quality and respectable TV recordings. Most engineers called the process (“kine”) pronounced “kinney” for short.

The Kinescope was quite the clever device. It’s film camera ran at a speed of 24 fps. Because the TV image repeated at 60 fields interlaced (30 fps) the film had to move intermittently between video frames and then be rock steady during exposure. The pull-down period for the film frame was during the vertical interval of less than 2ms, something no mechanical contraption could do at the time.

Several manufacturers like RCA, Acme, General Precision, and Eastman Kodak found various ways around the problem by creating a novel shutter system that used an extra six frames of the 30 frame video signal to move the film. This action integrated the video half-images into what seemed like smooth 24fps film pictures. Of course, the kines were played back on air using RCA film chains running at 24fps so the conversion to film was complete and seamless.

Until videotape recorders made their debut in 1956, the Kinescope was the only way to transmit delayed television programs which were all shot on film.

The RCA Kinescope Machine

On October 2, 2012

- TV History

The RCA Kinescope Machine

September 13, 1947 — Kodak and NBC develop ‘kinescopes’, which use special film cameras to shoot directly off a TV screen. This permits the recording and later distribution of live shows for sale, or archiving.

The Kinescope dominated TV recording for time delay in the early 1950’s. A Kinescope recorder was basically a special 16mm or 35mm film camera mounted in a large box aimed at a high quality monochrome video monitor. All things considered the Kinescope made high quality and respectable TV recordings.

The Kinescope was quite the clever device. It’s film camera ran at a speed of 24 fps. Because the TV image repeated at 60 fields interlaced (30 fps) the film had to move intermittantly between video frames and then be rock steady during exposure. The pull-down period for the film frame was during the vertical interval of less than 2ms, which was something no mechanical contraption could do at the time. Several manufacturers like RCA, Acme, General Precision, and Eastman Kodak found various ways around the problem by creating a novel shutter system that used an extra six frames of the 30 frame video signal to move the film. This action integrated the video half-images into what seemed like smooth 24fps film pictures. Of course, the kines were played back on air using film chains running at 24fps so the conversion to film was complete and seamless. Until videotape recorders made their debut, the Kinescope was the only way to transmit delayed television programs that were produced live.

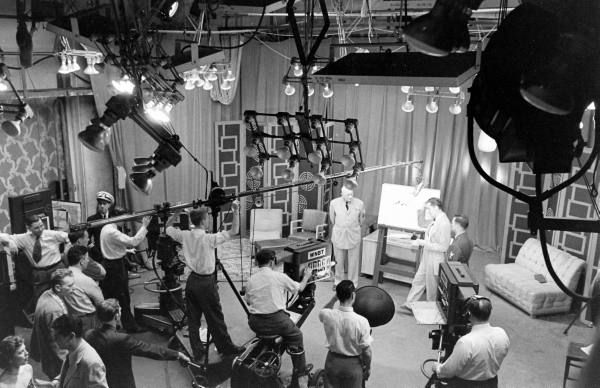

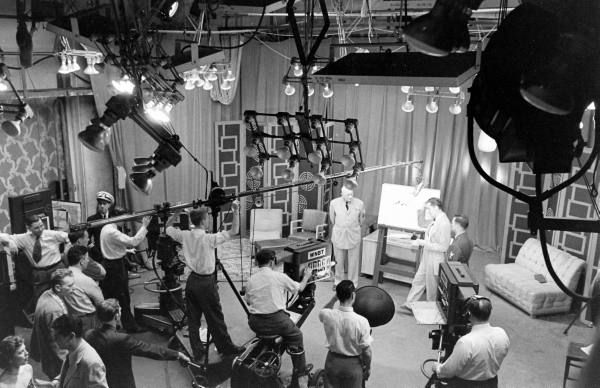

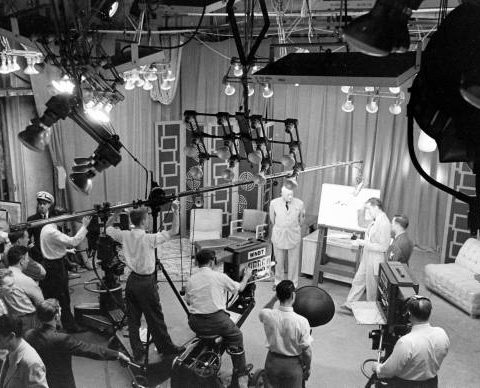

Ultra Rare…Inside NBC’s New York Studios 1950

On September 20, 2023

- TV History, Viewseum

As TV was taking off in 1950, NBC and others struggled to find studio space in New York. This rare film shows us, in more detail than we have ever seen, the course those efforts with a look inside not only the “Radio City” 30 Rock building, but also the International, Center and Hudson Theaters and thankfully, the “missing link” is shown here too…NBC’s Uptown Studios at 106th Street. There is a lot more here, including film of the NBC Kinescope department, the renovation of Studio 8H for TV, a new Master Control and much more. This film has been out of sight for decades but has now resurfaced, complete with narration by NBC’s first television news anchorman John Cameron Swayze.

A huge thanks to TV historian Alec Cumming and Ken Aymong at SNL for locating and preserving this fabulous NBC Studio history archive! -Bobby Ellerbee

Shooting Live TV Shows On Film By Karl Freund; “I Love Lucy” Director of Photography

On May 31, 2021

- Archives

Below this 1953 SMPTE article written by Karl Freund is a copy of his biography by IMBD writer John Hopwood. In the article Freund tells how he shot I Love Lucy and describes how he overcame unique new problems.

Karl Freund was born in Germany in 1890; by age 15 was working as a projectionist and by age 17, he had become a newsreel photographer. By 1926, he had earned a reputation for his skills in cinematography and his work on the classic Metropolis was his last job there before leaving for America.

Now possessing an international reputation, Freund emigrated to the U.S. in 1929, where he was employed by the Technicolor Co. to help perfect its color process. Subsequently, he was hired as a cinematographer and director by Universal Studios, where he cut his teeth, uncredited, as a cinematographer on the great anti-war classic All Quiet on the Western Front (1930), Universal’s first Oscar winner as Best Picture.

Universal’s bread and butter in the early 1930s were its horror films, and Freund was involved in the production of several classics. Among his Universal assignments, Freund shot Dracula (1931) and Murders in the Rue Morgue (1932), and directed The Mummy (1932). The Mummy (1932) was Freund’s first directorial effort, and co-star Zita Johann, who disliked Freund, claimed he was incompetent, which is unfair, seeing as how the film is now considered a classic of its genre. The film uses the undead sorcerer Imhotep’s pool with which he can impose his will over the living by spreading some tana leaves on the water, as a visual metaphor for the subconscious. The film is arresting visually due to Freund’s cinematic eye that created a sense of “otherness.” The film is infused with a dream-like state that seems rooted in the subconscious mind. Freund’s other directorial efforts at Universal proved less satisfying.

MGM wanted Freund for his genius at camera work. He shot the rooftop numbers for The Great Ziegfeld (1936), another Best Picture Oscar winner, and worked with William H. Daniels, Garbo’s favorite cameraman, on “Camille” (1936). He shot Greta Garbo’s Conquest (1937) solo, though he never worked with Garbo again. That same year, he was the director of photography on The Good Earth (1937), for which he won an Academy Award for Best Cinematography.

Other major MGM pictures he shot were Pride and Prejudice (1940), for which he received an Academy Award nomination, Tortilla Flat (1942), and A Guy Named Joe (1943). He also worked for other studios, shooting Golden Boy (1939) for Columbia. In 1942, he pulled off a rare double: he was nominated for Best Cinematography in both the black and white and color categories, for The Chocolate Soldier (1941) and Blossoms in the Dust (1941), respectively.

One of the last films he shot for MGM was Two Smart People (1946), starring Lucille Ball. In 1947, he moved on to Warner Bros, where he shot the classic Key Largo (1948) for John Huston. His last film as a director of photography was Michael Curtiz’ Montana (1950), which starred Gary Cooper.

Always the technical innovator, Freund founded the Photo Research Corp. in 1944, a laboratory for the development of new cinematographic techniques and equipment. His technical work culminated in his receipt of a Class II Technical Award in 1955 from the Motion Pictures Arts & Sciences for the design of a direct-reading light meter which is seen in the PDF article on this page. That same year, he had the honor of representing his adopted country at the International Conference on Illumination in Zurich, Switzerland.

It was perhaps inevitable that the technical and innovation-minded Freund would get to work for a brand new visual medium, television. Lucille Ball, whom he had photographed when she was a contract player at MGM, became his boss when he was hired as the director of photography at Desilu Productions, owned by Ball and her husband, Desi Arnaz. Desilu hired the great Freund as its owners were determined to shoot the show I Love Lucy (1951) on film rather than produce the show live, as was standard in the early 1950s. Most shows were shot live, while a film of the program was simultaneously shot from a monitor, a process that created a “kinescope.” The kinescope would be shown in other time zones on the network’s affiliates. Desilu’s owners disliked the quality of kinescopes, and needed Freund to come up with a solution to their problem of how to maintain the intimacy of a live show on film.

Freund agreed that the show should be shot on film rather than live, as film enabled thorough planning and allowed for cutting, which was impossible with live TV. Freud knew that film would allow Desilu to eliminate the fluffs which were a staple of early television, and would allow the producers to re-shoot scenes to improve the show, if needed.

I Love Lucy had to be filmed before an audience to retain the immediacy of a live TV show, which meant that the traditional, time-consuming methods of studio production with one camera would not work. Freund decided to shoot I Love Lucy with three 35mm Mitchell BNC cameras, one of each to simultaneously shoot long shots, medium shots and close-ups. Thus, the editor would have adequate coverage to create the 22 minutes of footage needed for a half-hour commercial network show.

The then-innovative, now-standard technique of simultaneously shooting a situation comedy with three 35mm cameras cut the production time needed to produce a 22-minute program to one-hour. The cameras were mounted on dollies, with the center camera outfitted with a 40mm wide-angle lens, and the side cameras outfitted with 3- and 4-inch lenses. The resulting shots were edited on a Movieola. A script girl in a booth overlooking the stage cued the camera operators. Due to extensive rehearsal time before the show was shot live, the camera operators had floor marks to guide them, but Freund’s system was enabled by the script girl overseeing their actions via a 2-way intercom. The system made the shooting, breaking-down, and setting-up process for the next scenes on the three sets of the I Love Lucy (1951) stage very economical in terms of time, averaging one and one-half minutes between shots.

Freund worked out the lighting during the rehearsal period. Almost all of the lighting was overhead, except for portable fill lights mounted above the matte box on each camera. In Freund’s system, there were no lighting changes during shooting, other than the use of a dimming board. Since the lighting was mounted overhead on catwalks, power cables were kept off the floor, which facilitated the dollying that was essential for making the system work fluidly.

Freund’s solution to the problem of shooting a show on film economically was to make lighting as uniform as possible, taking advantage of adding highlights whenever possible, since a comedy show required high-key illumination. Due to the high contrast of the tubes in the image pickup systems at the television stations, contrast was a potential problem, as any contrast in the film would be exaggerated upon transmission of the film. To keep the film contrast to what Freund called a “fine medium,” the sets were painted in various shades of gray. Props and costumes also were gray to promote a uniformity of color and tone that would not defeat Freund’s carefully devised illumination scheme.

In a typical workweek, the I Love Lucy (1951) company engaged in pre-production planning and rehearsals on Monday through Thursday. I Love Lucy (1951) was filmed before a live audience at 8:00 o’clock PM on Friday evenings, and Freund’s camera crew worked only on that Friday and the preceding Thursday. Freund, however, attended the Wednesday afternoon rehearsal of the cast to study the movements of the players around the sets, noting the blocking and their entrances and exits, in order to plan his lighting and camera work. Thursday morning at 8:00 o’clock AM, Freund and the gaffers would begin lighting the sets, which typically would be done by noon, the time the camera crew was required to report on set to be briefed on camera movements. Then, Freund would rehearse the camera action in order to make necessary changes in the lighting and the dollying of the cameras.

It was during the Thursday full-crew rehearsal that the cues for the dimmer operator were set, and the floor was marked to indicate the cameras’ positions for various shots. For each shot, the focus was pre-measured and noted for each camera position with chalk marks on the stage floor. Another rehearsal was held at 4:30 PM with the full production crew. Though a full-dress rehearsal was held at 7:30 PM, with the attendance of the full crew, the cameras were not brought onto the set. The director would take the opportunity to discuss the plan of the show and solicit input from the cast and crew on how to tighten the show and improve its pacing.

The next call for the entire company was at 1:00 PM on Friday to discuss any major changes that were discussed the previous night. After this meeting, the cameras would be brought out onto the stage, and at 4:30 PM, there would be a final dress rehearsal during which Freund would check his lighting and make any required changes.

After a dinner break, the cast and production crew would hold a “talk through” of the show to solicit further suggestions and solve any remaining problems. At 8:00 PM, the cast and production crew were ready to start filming the show before a live audience. Before shooting, one of the cast or a member of the company had briefed the audience on the filming procedure, emphasizing the need for the audience’s reactions to be spontaneous and natural.

Shooting was over in about an hour due to the rapid set-ups and break-downs of the crew, which shot the show in chronological order. Due to the thorough planning and rehearsals, retakes were seldom necessary. Camera operators in Freund’s system had to make each take the right way the first time, every time, to keep the system working smoothly, and they did. An average of 7,500 feet of film was shot for each show at a cost that was significantly less than a comparable major studio production.

Freund also served as the cinematographer on the TV series Our Miss Brooks (1952), which was shot at Desilu Studios, and Desilu’s own December Bride (1954). It was no accident that Desilu productions turned to Karl Freund to realize their dream of creating a high-quality show on film. Freund had the broadest experience of any cameraman of his stature, starting in silent pictures, and then excelling in both B&W and color in the sound era. With his penchant for technical innovation, he was the ideal man to develop solutions for filming a television show. Freund met the challenge of creating high quality filmed images in a young medium still handicapped by its primitive technology.

Freund became the dean of cinematographers in a new medium, with Desilu’s I Love Lucy and its other shows recognized as the gold standard for TV production. His work ensured the fortunes of Desilu Productions, and the personal fortunes of Desilu owners Desi Arnaz and Lucille Ball, as he provided them with quality films of each show that could be easily syndicated into perpetuity, whereas the live shows filmed secondarily off of flickering TV monitors as kinescopes could not.

After retiring as a cinematographer, Freund continued his research at the Photo Research Corp. He died on May 3, 1969.

– IMDb Mini Biography By: Jon C. Hopwood