December 24,1951…Behind The Scenes Inside NBC Studio 8H

December 24,1951…Behind The Scenes Inside NBC Studio 8H

1st “Hallmark Hall Of Fame”…1st “Amahl And The Night Visitors”

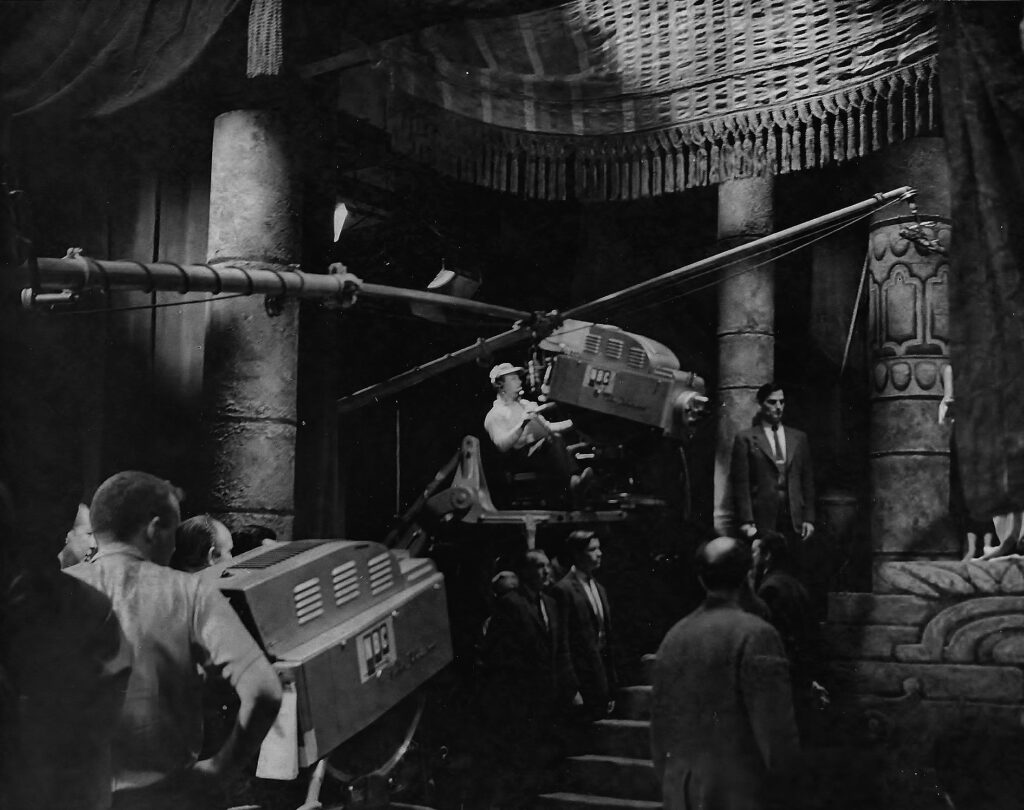

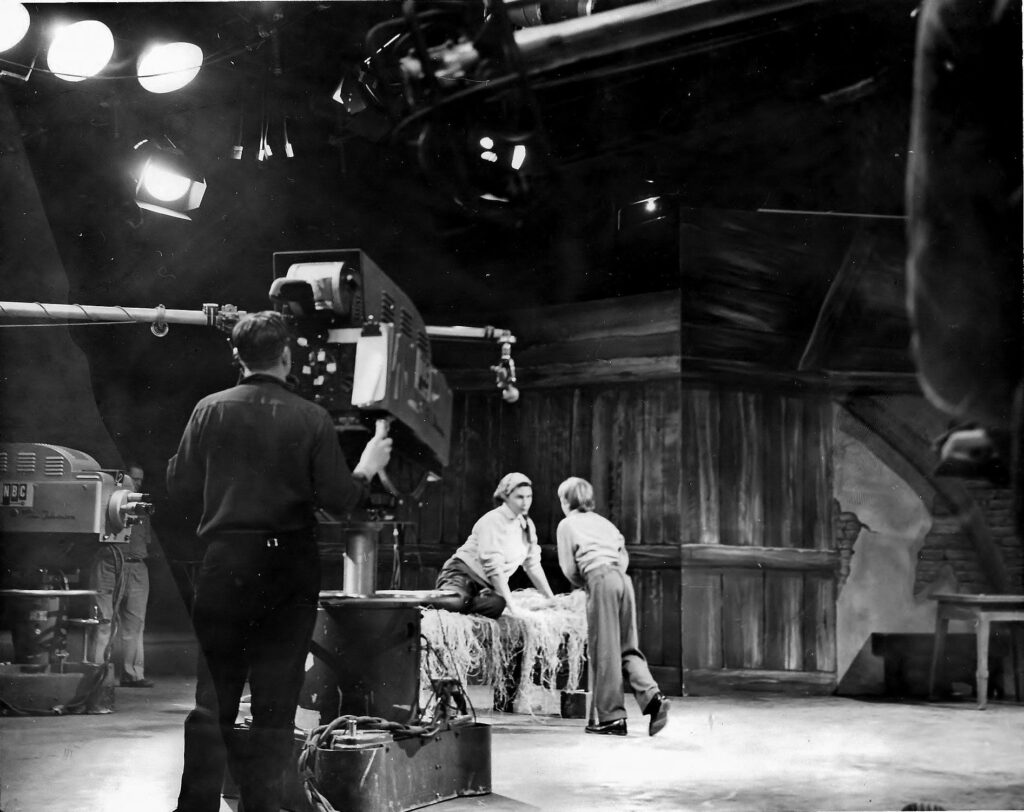

This story has two parts. Below the 3 photos of the RCA TK41s shooting this production at NBC Brooklyn, is an interesting first hand account from a TV magazine writer who was there, pointing out the production obstacles they needed to overcome to present the debut of what would become two enduring programs.

The above the photos story starts here with some notes on the historic aspects of what was about to happen.

At 9:30 PM on December 24, 1951, in NBC Studio 8-H, the first opera ever written expressly for television went live on the air. The sponsor for the NBC holiday spectacular was Hallmark Cards. This was their first venture into television and this lead to the development of the now famous “Hallmark Hall Of Fame” series.

Above is the kinescope recording of the original 1951 production. The show was done live each year for many years till video tape came along. In 1954 it was done in color at NBC Brooklyn, and in ’63, finally recorded on color video tape at the Brooklyn facility. In the photo at the top of this page, we see one of the four monochrome cameras used on the show in 8H shooting the child lead, Chet Allen. The cameraman is NBC’s first studio cameraman, Albert Protzman who was hired in 1936.

Below is a description of that night in 8H from TV Party Magazine by Mitchel Hadley. The full article is at this link. -Bobby Ellerbee http://www.tvparty.com/xmas-amahl.html

_____________________________________________________

Christmas Eve in Studio 8H

The scene was a dramatic one – and, par for the course for early television, far from ideal. For one thing, although 8-H was the largest television studio in America, it wasn’t nearly large enough for the cast, crew, and musicians. The result, among other things, was that singers and orchestra would have no direct contact with each other. The orchestra was located in Studio 8G…the conductor could see the action on the set via the monitors while the singers would hear the music piped in through speakers in the studio.

Up in the control room would be Director Kurt Browning. At his disposal were four cameras – three inside the “hut” where Amahl and his mother lived, and one outside – and three boom microphones, one between each camera. His “control” was far from absolute, however; union rules of the era prevented the director from speaking directly to the cameramen, requiring him to go through the technical director to communicate his instructions. Such an arrangement was a recipe for disaster, especially for a live broadcast. Menotti was no stranger to the challenges of television, though, and he and Browning worked closely on the camera script, ensuring that there would be no spare gesture, no extraneous movement that would throw an actor out of frame.

The cumbersome equipment of the time would also prove to be a challenge, as Browning recalled in a 1994 interview. “As I remember, I had pedestal cameras which weighed four to five hundred pounds and a dolly camera that weighed another seven to eight hundred pounds. Movement was limited, however, for “once you got over a 90mm lens, you couldn’t move the camera because the movement registered on the camera and you would lose focus almost immediately.”

On the set itself the cast, after a month of preparation and anticipation (but only four actual days in the studio), was ready.

When the camera light winked on at 9:30, viewers saw a blurred image of church bells, followed by a title card announcing that the following program was presented by Hallmark. It is often stated that the actress Sarah Churchill hosted that first broadcast, since she subsequently served as host of Hall of Fame for the first couple of years, but in fact it was Nelson Case, host of NBC’s Armstrong Circle Theater, who greeted the audience. (Amahl was, in fact, being presented in Armstrong’s regular Tuesday night time slot.) After a solemn, if overlong, introduction, Case presented Menotti, who stood on a set in front of a fake fireplace decorated with garland, the Bosch painting hanging over the mantle.

Speaking from notes and in Italian-accented English, Menotti said he hoped that parents had allowed their children to stay up late for the broadcast, since the opera had been written for them and “I don’t want you to be like those awful parents who insist on playing with their children’s toys.” He then introduced the people who had helped make Amahl possible, asking them to join him on camera since the audience “won’t see [them] while the opera goes on”: Browning, who “photographed this opera the way I saw it in the windows of my imagination,” Schippers, who “captured the sounds of my childhood,” and set designer Eugene Berman, “who designed the sets that come straight out of my own heart.”

As a series of handwritten slides (taking a moment to come into focus) introduced the cast and crew, the overture began in the background – a tender, moving melody that soon gave way to the sound of a pipe. The camera dissolved to a star high in the sky, and then slowly panned down to a young boy playing the pipe. Amahl and the Night Visitors had begun.

Here it is worth noting that the broadcast features a fascinating attempt at a primitive “special effect.” Menotti wanted the approach of the Kings to suggest a journey of a great distance. The entrance of the Kings began, therefore, with only their voices being heard. While Amahl and his mother lie sleeping, the camera zoomed in on a close up of Rosemary Kuhlmann. Then, using her back as a movie screen, a pre recorded film of the Kings’ entry was projected.

Browning then cut to a shot of Kuhlmann from a different angle, while the lyrics “the shepherd dreams inside the fold” were sung – suggesting, subtly, that the Kings might be nothing more than a dream. It was a complex effect, sophisticated for the time, especially for live television. It’s not known how many times this effect was used in subsequent broadcasts of Amahl; by 1955 it had been replaced by a simple cut from the inside of the hut to the outdoor set.

~ Thank-you for posting-sharing. Wonderful. ~ The very best filmed version of “Les Miserable” was an ITC production for the “Hall of Fame” on CBS in 1978 starring Richard Jordan, Anthony Perkins, Cyril Cusack, John Gielgud, Ian Holm, Caroline Langrishe, & Angela Pleasence as Fantine. I feel fortunate to own a DVD copy.

Talk about back problems! Worse than a 76 on the shoulder.

I remember watching it!

Remember this show.

Not pictured: Floor manager Fred Rogers. Yes, THAT Fred Rogers.