By Jodie Peeler

As NASA committed to its manned spaceflights taking place in the open before the eyes of the world, there came the problem of how to cover each mission’s end. The earliest flights took place before commercial TV satellites were a reality, and the best the networks could do was station a reporter aboard the recovery ship to provide voice reports; later, film or videotape of the splashdown and recovery would be shown by the networks. Live reports had to make do with voice reports, supported by something like this slide from NBC’s coverage of Gus Grissom’s Mercury-Redstone 4 mission in July 1961:

This changed in late 1965 when the networks, with the help of COMSAT and ITT, finally had the capability to beam live television from the recovery ship via Early Bird. The system was ready to go for the planned October 1965 flight of Gemini 6, and a large satellite dish was temporarily mounted on the flight deck of the prime recovery ship, the aircraft carrier USS Wasp. Gemini 6 was postponed, however, when its rendezvous target vehicle was lost after launch. Instead, NASA decided to launch Gemini 7 in December 1965 and send Gemini 6A to meet up with it, the first rendezvous by two manned American spacecraft and an important step on the way to the Moon. With USS Wasp still selected as prime recovery ship, the seagoing earth station got a spectacular debut: Gemini 6’s return on December 16, and Gemini 7’s two days later. Both splashdowns were carried live by the networks, with pool coverage from Dallas Townsend and Bernard Eismann.

Below are some pictures of the Gemini 6A/7 recovery. Note, among other things, the camera position high on the island near the gun director (which became a favored location for cameras aboard these ships during recovery missions), and the massive earth station on the flight deck.

Tampa’s CBS affiliate WTVT often lent a hand on space shots that concluded with an Atlantic splashdown. Prior to Gemini 6A/Gemini 7, WTVT-TV’s unit and crew had been on a couple of recovery deployments to videotape the recovery efforts and microwave the pictures back once within range. Here’s the mobile unit at Mayport, Florida with the carrier Randolph in the background, there either for Gus Grissom’s 1961 Mercury flight or John Glenn’s 1962 Mercury flight.

And it was WTVT that was aboard Wasp for the first recoveries televised via satellite. Here’s WTVT cameraman Jim Benedict with his TK11/31 aboard Wasp during this historic deployment. There’s more on this at our friend Mike Clark’s Big 13 site.

Although there were technical problems still to be resolved, and although the picture was lost at a few points, the first live “splashcast” demonstrated it could be done, and it soon became a staple of spaceflight coverage.

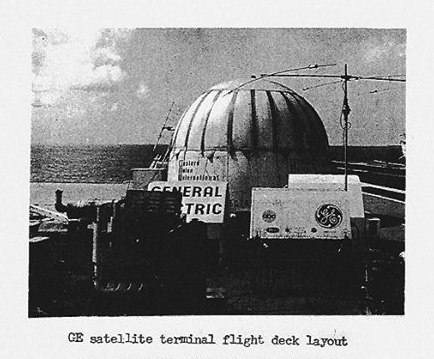

Live color transmission from the recovery ship finally became a reality in October 1968, with live pictures of the Apollo 7 recovery from the recovery carrier USS Essex. Part of what made it possible is in the picture above. See that big white dome just above the “7” spelled out on deck? Underneath that inflatable dome was a new portable earth station developed by General Electric and Western Union International. It was designed to fold and unfold like an umbrella. Once unfolded, it was protected by that big 22-foot inflatable radome. It stayed locked on the satellite via a beacon signal system that allowed instantaneous corrections. That big white dome became a familiar sight on recovery ships throughout the days of Apollo.

This Western Union International commercial, which aired during the Apollo 11 mission, gives a brief overview of how the system worked.

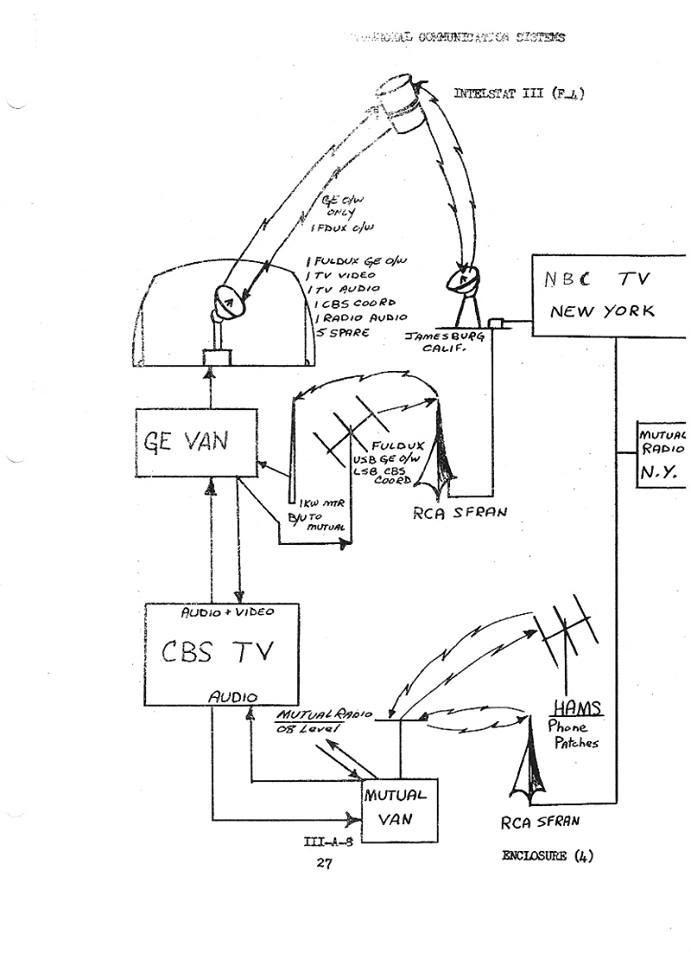

Apollo 7’s splashdown in the Atlantic, where most Gemini flights had ended, gave the new system its first trial in familiar territory, but the recovery of Apollo 8 in December 1968 provided the challenge of getting pictures from far off in the Pacific Ocean, where all the lunar flights would come back. This diagram from the Apollo 12 recovery will give you an idea of the logistics involved in getting audio and video back to the United States from the middle of the Pacific.

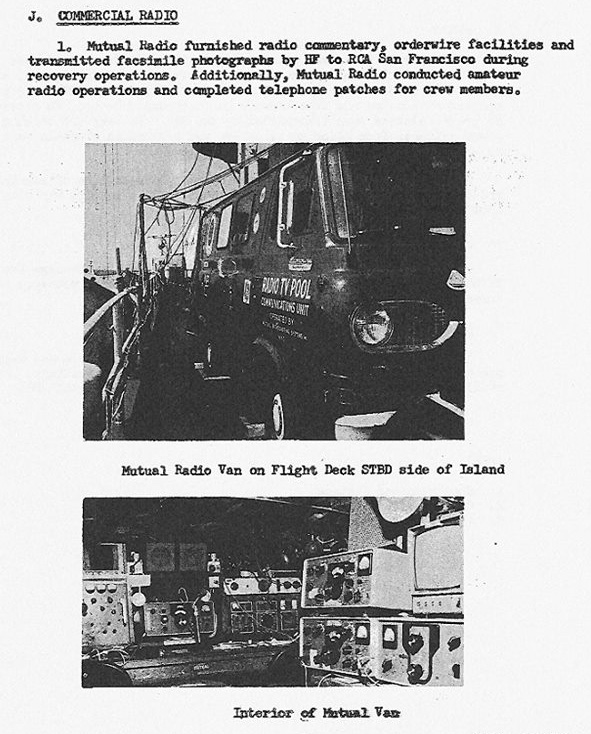

Note the “Mutual Van” in the above diagram. This common sight aboard recovery carriers was the Mutual Broadcasting System’s unit, a green 1965 Ford Econoline van. You can see it inside the circle here:

The little green van provided radio support for the press pool on board, and was beloved by the ship’s company because its operator, Jim O’Connor, provided patches for them to call back home.

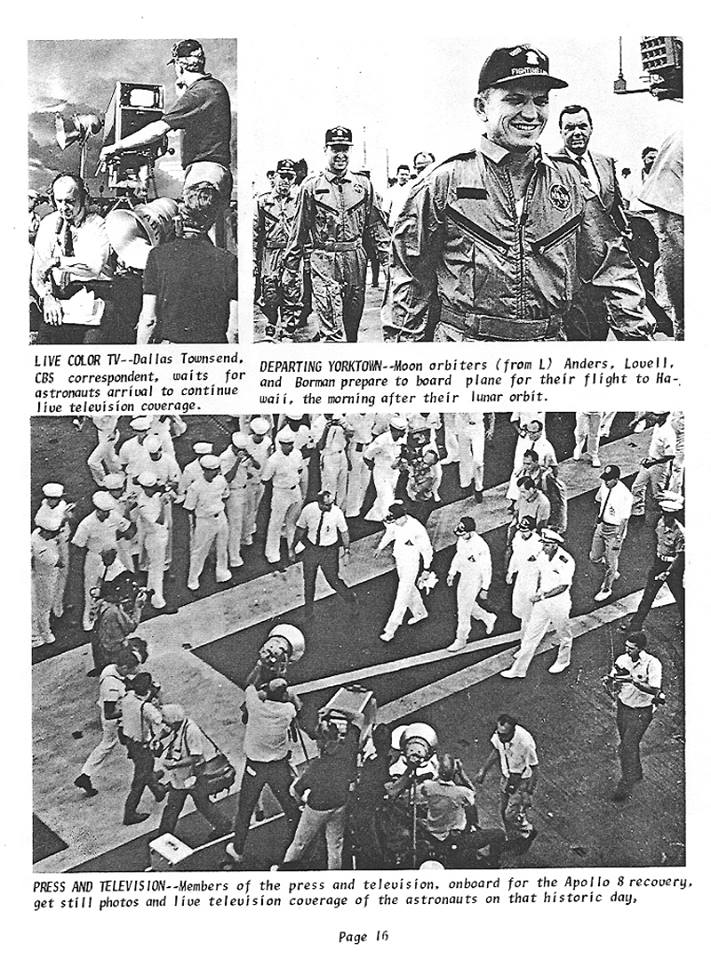

Some difficulties were encountered early in the Apollo 8 splashdown coverage – the ship’s powerful radar units didn’t get along with some radio and satellite equipment, and the signal was lost a few times – but on December 27, 1968 viewers were able to watch live as the Apollo 8 astronauts ended man’s first flight around the Moon as they emerged from the recovery helicopter aboard USS Yorktown. Portable cameras allowed viewers a close-up look as the astronauts went from the flight deck to the hangar deck below.

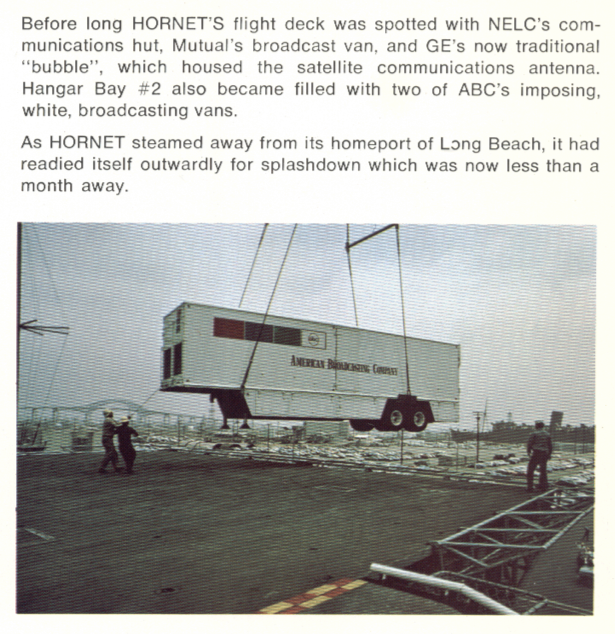

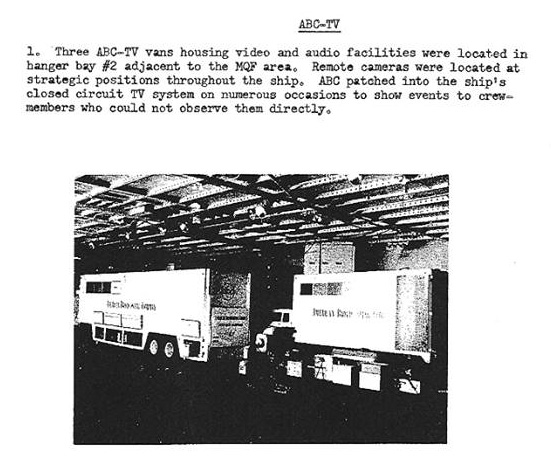

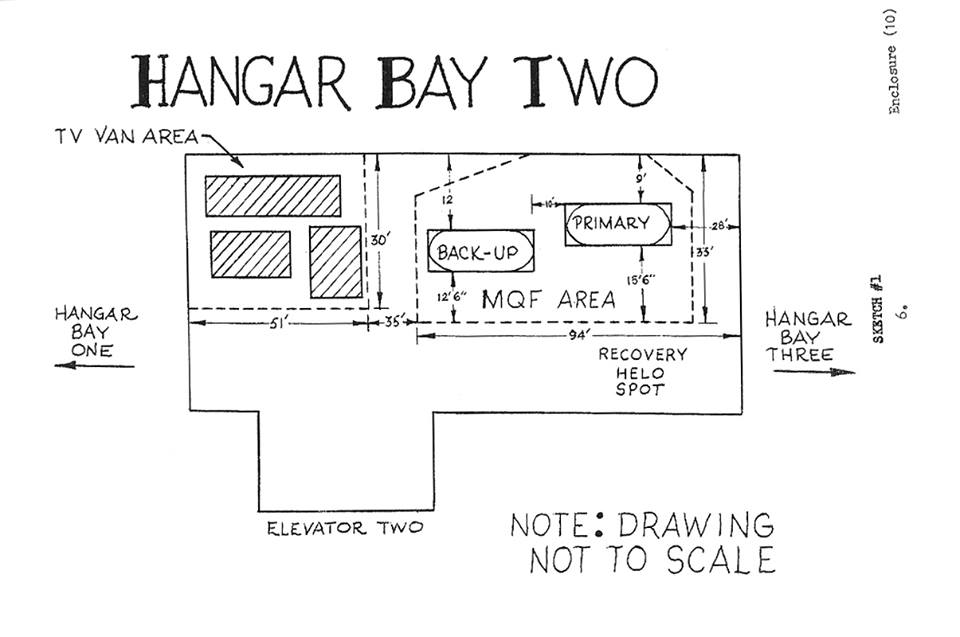

With Apollo 8’s lessons learned, and further refinements during the Apollo 9 and Apollo 10 recovery efforts, all was in place for the historic Apollo 11 recovery by USS Hornet on July 24, 1969. The networks rotated responsibility for the television pool, and ABC had the duty for Apollo 11.

Increased cooperation among the Navy, GE/WUI, and the networks meant coverage went better and with minimal technical glitches. Viewers were able to watch live pictures from Hornet: the recovery efforts, the astronauts landing aboard and going into their quarantine van, and the welcome-home ceremony in which President Nixon, aboard the ship to witness the historic moment, gave the astronauts an official welcome.

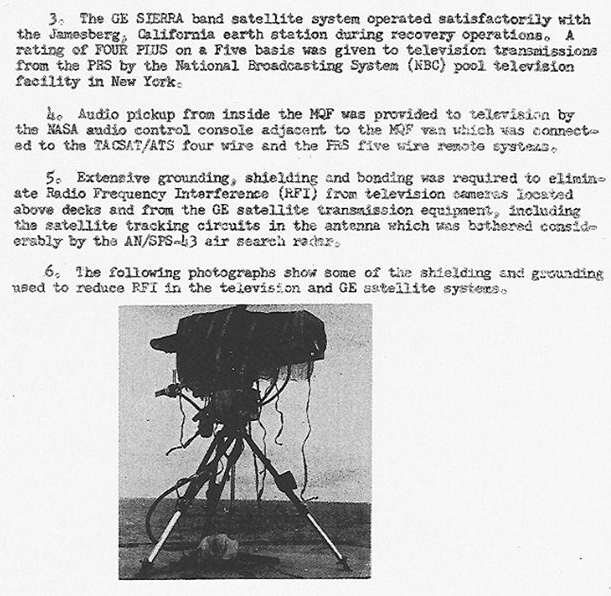

As television professionals and the Navy built experience with televised recoveries, solutions came along that made coverage that much better. For instance, it was found that draping cameras in mumetal helped protect them from the interference from carriers’ powerful air-search radar.

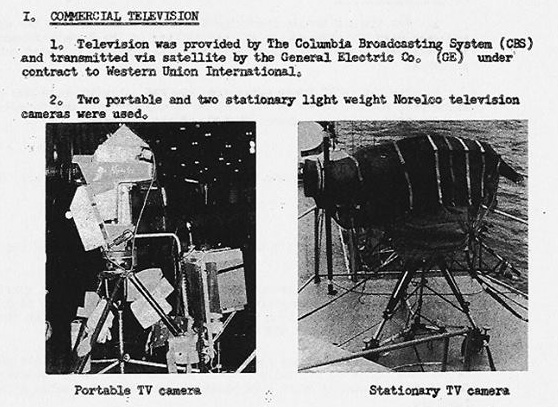

Above are pictures of Norelco PC 70s and a PCP 70 used on the Apollo 12 recovery. Note the mumetal protection around the PC 70s.

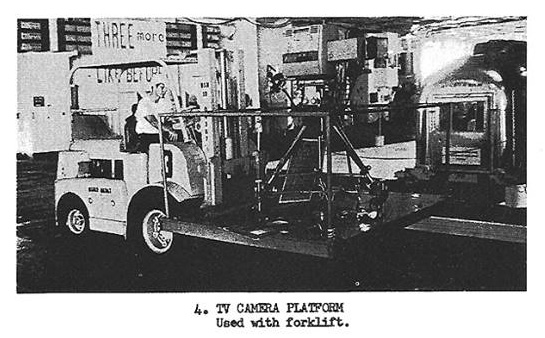

The Navy also worked with the networks in other ways. Here’s a Navy forklift that served as a mobile platform for a Norelco on the Apollo 12 recovery.

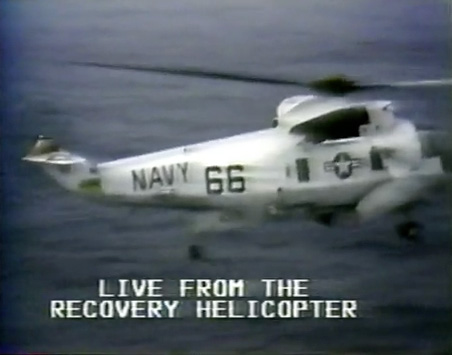

And the Apollo 13 recovery brought another innovation: live television direct from the recovery scene via the nearby photo helicopter.

Although live coverage from the recovery ships continued through the remainder of the Apollo program, interest peaked with Apollo 11 and steadily dwindled, with the dramatic return of Apollo 13 the exception. Apollo became an old story, and the networks cut back on their coverage. By 1972 CBS News president Dick Salant was balking at the $200,000 or so it would cost to carry live coverage of the splashdown of Apollo 17, the final lunar mission (and in spite of his protest, CBS did carry the splashdown live). Still, the historic moments of Apollo had been carried from start to finish, and the world had been able to see its lunar explorers return home safely.