- Home

- TV History

- Network Studios History

- Cameras

- Archives

- Viewseum

- About / Comments

Skip to content

Search Results for: kinescope

October 4, 1956…’Playhouse 90′ Debuts on CBS

On October 4, 2014

- TV History, Viewseum

October 4, 1956…’Playhouse 90′ Debuts on CBS

Thursday nights at 9:30 eastern, television’s most distinguished dramatic anthology series was anxiously awaited in most American living rooms. Below is a full episode of the show that you will want to see...it’s full of RCA TK11s and many Television City studio shots all the way through. This is “The Comedian” starring Mickey Rooney and Mel Torme. It was written by Rod Serling and directed by the great John Frankenheimer and live ran on February 14, 1957. This is a kinescope copy of Season 1’s, Episode 20.

From it’s inception in 1956, everyone knew that this 90 minute weekly presentation was a big bite for any production schedule…even the new CBS Television City facility. So, that first year, three out of four episodes were done live with every fourth episode being done on film at another location.

Remember, the worldwide debut of video tape was in April of 1956 and it took nearly a year to get some machines built and in use, but soon after CBS TVC got theirs, they began to experiment with using them on ‘Playhouse 90’. Although the were live to tape, with no editing, having this ability helped a lot, and in early ’57, the show moved completely to videotape.

The move to tape allowed the show to keep it’s live look and best of all, it allowed them to break the 90 minute show into segments and gave them the ability to retake scenes and move sets without the urgency of the live clock against them.

In the final ’59 – ’60 season, the pressures and cost of this truly ambitious effort proved overwhelming and ‘Playhouse 90’ cut back to alternate weeks and rotated with ‘The Big Party’, which was a 90 minute celebrity talk and variety show. Enjoy and Share! -Bobby Ellerbee

October 1, 1952…’This Is Your Life’ Debuts On NBC

On October 1, 2014

- TV History

October 1, 1952…’This Is Your Life’ Debuts On NBC

‘This Is Your Life’ had its genesis in radio as a good natured gesture on the ‘Truth or Consequences’ show in 1946. General Omar Bradley asked Ralph Edwards to do something to help returning World War II veterans, especially paraplegics. He said they were depressed and reluctant to see anyone, including their families. Ralph’s ingenious solution was to profile a returning hero on his radio program, which created a “voice” for all veterans. Lawrence Tranter was selected as the first honoree. His story was told by surprising him with people from his past – family, friends, school teachers, and others in an emotion-filled episode. Knowing Tranter had ambitions to be a watch repair technician, the show arranged for him to attend the Bulova School of Watchmaking in New York.

‘This Is Your Life’ began its official TV run on October 1, 1952 with the life of Laura Stone Marr, mother of actor Milburn Stone who we best remember as “Doc” on Gunsmoke. An instant hit on NBC, the show virtually stopped America in its tracks every Wednesday night and ran till 1961.

This was among the first NBC series to originate from California, so in order to get this on the air in the east in early prime time the show had to start in late afternoon with a kinescope broadcast for the west coast. The reason the east rarely ran a kine was that most of the nation’s population was there…the most viewers got the best quality.

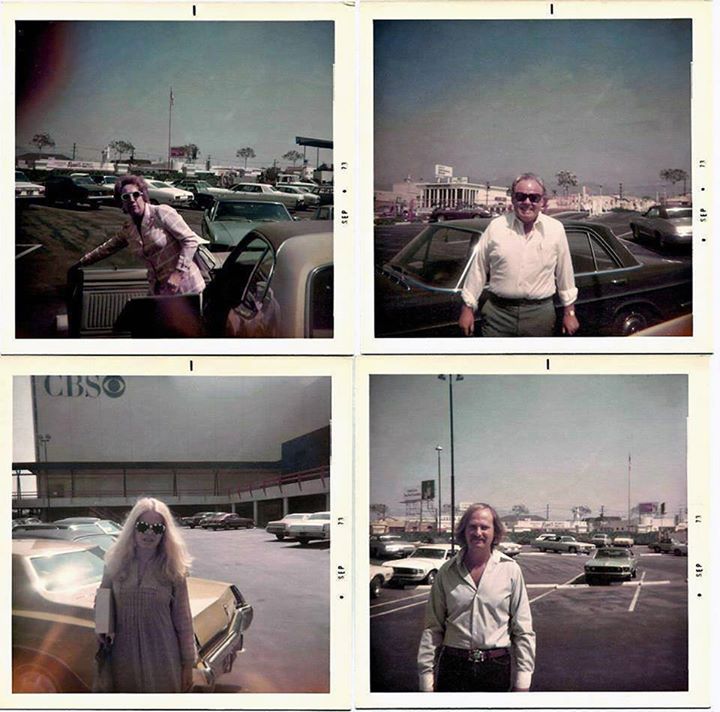

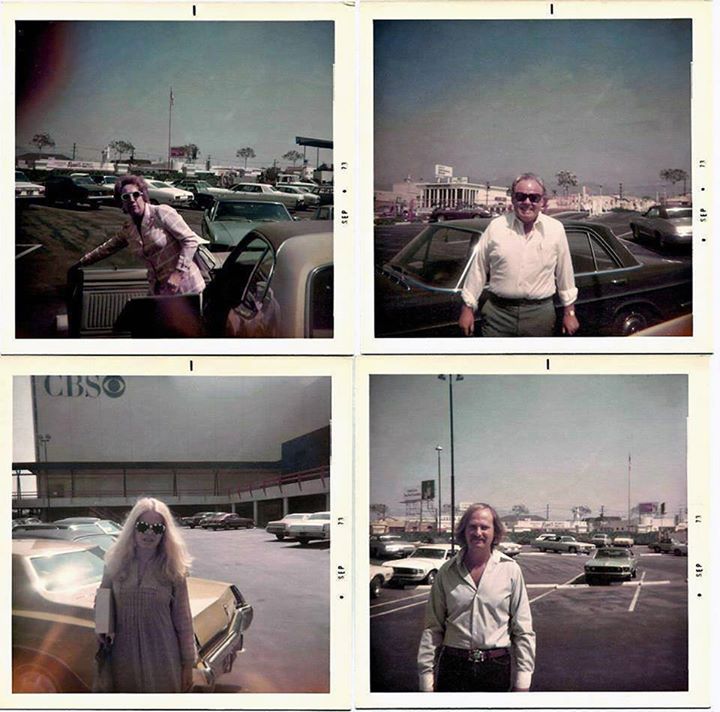

The photos below are from the 1958 Francis Farmer episode and were taken by the father of Jim Early. Thanks to Jim for sharing them with us as these are the only known color photos of the show. Enjoy and share! – Bobby Ellerbee

Ever See The Gemini System In Action?

On September 29, 2014

- Archives, TV History

Dumont was first with this video/film hybrid system which they called the Electronicam, and it debuted just before it was used on ‘The Honeymooners’ Classic 39 film episodes in 1954.

This Gemini System from UK optics company Rank (as in Rank, Taylor, Hobson) came out around 1957, and as the Broadcasting Magazine article states, would eliminate the need for Kinescopes. The problem for Rank was that videotape had just debuted too, but there was a need and use for this…especially when it came to commercial production.

Soon after videotape went into service at the networks, national sponsors began asking for their spots on tape. In order to avoid having to shoot the spots twice, once of film cameras and once for television cameras – or to avoid having a kine print, the Gemini came in handy for shooting both at the same time.

Even into the early 60s, many local stations only had one or two of the expensive video tape machines and still had to run spot from film via telecine chains. Thanks to John Schipp for the article. Enjoy and share! -Bobby Ellerbee

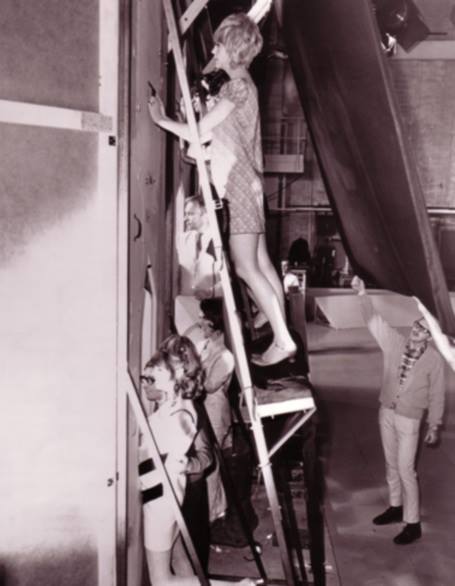

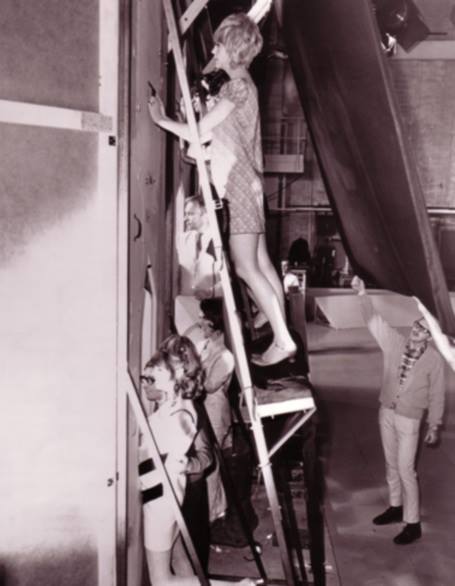

A-MAZE-ING: Live Television

On September 26, 2014

- TV History

This NYC shot is a stark contrast to the way live production changed once bigger studios, like the ones at Television City, allowed horizontal staging…sets, all in a row that allowed crews and cameras to move side to side on the stage.

This photo could possibly be from the newly converted CBS Studio 50, which is now home to David Letterman. It was converted from radio to television in 1950 and this shot from the catwalk shows three RCA TK10s within 6 feet of each other ready to shoot three different scenes on this maze like set. The production is the 1950 “Studio One’ presentation of ‘The Scarlet Letter’. In 1950, ‘Studio One’ won an Emmy for Best Kinescope.

Notice the low camera in the top left is shooting into the rear of a fireplace opening and soon, will give us an image of one of the characters putting wood on the fire from inside the fireplace, but first the camera on the other side of the wall has to move. Enjoy and share! -Bobby Ellerbee

September 21, 1957…’Perry Mason’ Debuts On CBS

On September 21, 2014

- TV History

September 21, 1957…’Perry Mason’ Debuts On CBS

I have two rare videos to share with you on ‘Perry Mason’.

The first one (linked above) is Raymond Burr’s screentest for the lead role. This looks like a video tape, but could be a kinescope which was most likely shot at the CBS Television City.

Next up is a rare interview with Raymond Burr on the set, conducted by the well known Scottish born, Canadian journalist Jack Webster in 1963 when the show was in it’s seventh season. The original series would run for nine seasons and ended in 1966 after 271 episodes…one of which was shot in color. “Tale Of The Twice Told Twist” was the color episode and aired near the last of the final season in February of 1966. I think CBS ordered it as it considered extending the show for another few seasons.

The first ever episode of ‘Perry Mason’ that aired 57 years ago today was “The Case Of The Wrestles Redhead”.

To this day, ‘Perry Mason’ is still one of my all-time favorite shows. It was smart and well done. To me, the only thing that dates the show is the lack of cell phones…how many times could Perry and Paul have saved the day earlier by not having to stop at pay phone or call Della for messages? Enjoy and share! -Bobby Ellerbee

Seemingly born to play ‘Perry Mason’, Raymond Burr did have to test for the role. The woman playing ‘Della Street’ is a bit too provocative for the character…

A Special 4 Star Whammy…Carson And Three Top Cartoon Voices

On August 31, 2014

- TV History

A Special 4 Star Whammy…Carson And Three Top Cartoon Voices

First off, the lead segment of this 1955 kinescope of ‘The Johnny Carson Show’ on CBS is some of the best quality I’ve ever seen. The last part with Johnny as a reporter is more typical of kine quality, or lack there off.

Johnny’s wife is played by the great June Foray who as we all know by now was most famous for her roles as Rocky and Natasha on ‘The Adventures Of Rocky And Bullwinkle’.

In the clip’s Bonus Footage section, we get to see Sara Berner as the older lady in the French sketch. Among other things, she was the voice of Andy Panda, Chilly Willie and Jerry The Mouse who was Fred Astaire’s animated dancing partner in ‘Anchors Aweigh’. Like June Foray, she did hundreds of other voices in MGM and Warner Brothers cartoons.

John Stephenson plays a news man here, and is probably best known as Fred Flintstone’s boss…Mr. Slate. He also did a lot of voices on ‘Scooby Doo’ and ‘Johnny Quest’. Stevenson also shared the narration duties on ‘Dragnet’ with George Fenneman. Enjoy and share! – Bobby Ellerbee

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ZDd1TU-Paa0

June Foray making a rare on-screen appearance on the Johnny Carson show on CBS some time around September 1955 and sounding very much like Rocky the Flying S…

A Tribute To ‘Captain Kangaroo’ You’ll Want To Read, HEAR

On August 26, 2014

- TV History

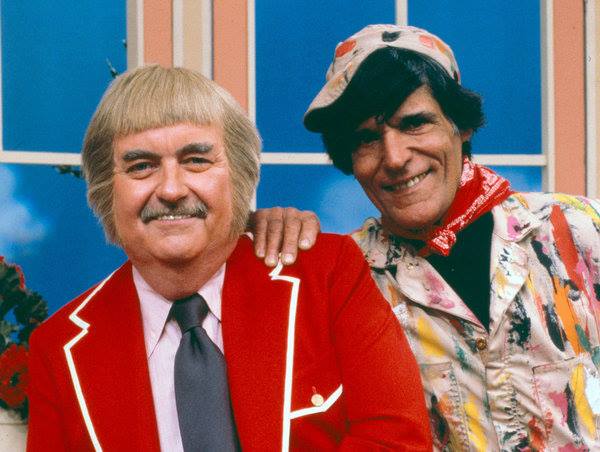

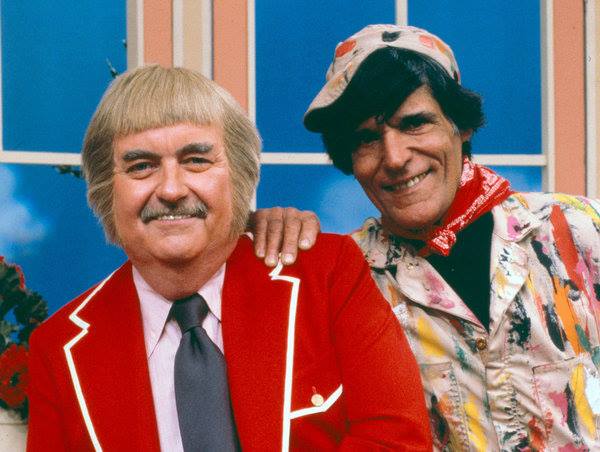

A Tribute To ‘Captain Kangaroo’ You’ll Want To Read, HEAR And Share!

Today is the first time I ever knew the name of this show’s famous theme song, much less, heard the full 2:43 version of “Puffin Billy”.

At this link is the original full version. The ‘Captain Kangaroo’ theme we heard on television was an edited version that repeated the first two verses over and over, but never allowed us to hear the bridge and nice half step up into the final verses that come around 1:08.

“Puffin Billy” was an instrumental, written by Edward G. White in 1934. The track was from a British stock music production library known as the Chappell Recorded Music Library which was sold through a New York agency called Emil Ascher. The tune’s original title referred to a British steam locomotive which is now on display in Melbourne, Australia.

You’ll never guess who the man in the photo is…even if I told you his name…Cosmo Allegretti. He was on the show every day, but we never saw him. Cosmo was the puppet master of the show! He did Bunny Rabbit, Grandfather Clock, Dancing Bear and more.

By the way, I just read yesterday that before videotape came along, Bob Keeshan and company did this two hour show live twice in a row, six days a week with only a :40 second break between the live east coast broadcast and the live west coast broadcast. There was no time for a Kinescope and they did this for three years from 1955 till 1958. Amazing! Enjoy and SHARE THIS! – Bobby Ellerbee

The Photo And The COLOR Video…’Hallmark Hall Of Fame’

On August 18, 2014

- TV History

Ultra Rare! The Photo And The COLOR Video…’Hallmark Hall Of Fame’

On October 18, 1964, Hallmark’s production of the popular Broadway musical “The Fantasticks” came to television. At the link above, the video is cued to start at the head of this scene in the photo that shows John Davidson speaking to his father, who is played by Bert Lahr.

This was done live to tape at NBC Brooklyn. Although videotape could be edited then, it was still done manually by splicing so the prefered method was still to go live in the east and tape for the west, just like in the kinescope days.

‘The Hallmark Hall of Fame’ debuted on Christmas Eve 1951, with the world premiere of “Amahl and the Night Visitors” on NBC TV. Until 1955, the production schedule was near frantic with an average of 40 new presentations a year. In 1954, the show began color broadcasts and in 1956, it went to a bi monthly format with six or seven shows a year.

The Hallmark anthology series was one of the highest rated and most awarded in television history. For nearly three decades the series was broadcast by NBC, but the network cancelled it in late 1978 due to declining ratings. Since then, the series has been televised by CBS from 1979 to 1989, then on ABC from 1989 to 1995, then CBS again from 1995 until 2011, when that network cancelled the series due to low ratings. As of 2014, the series has earned 80 Emmys, 9 Golden Globes, 11 Peabody Awards and many others.

Thanks to Paul Duca for finding the video. Enjoy and share!

– Bobby Ellerbee

Remembering Lauren Bacall…Her Television Debut

On August 13, 2014

- TV History

Remembering Lauren Bacall…Her Television Debut

This photo of Bacall, Fonda and Bogart was taken at NBC Burbank on May 30, 1955 during the dress rehearsal of a ‘Producer’s Showcase’ presentation of “Petrified Forest”…this was Lauren Bacall’s first appearance in a live television drama.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=riylfh_9ir8

At the link is a rare kinescope of that performance. This, the only known copy, was given to The Paley Center For Media by Bacall herself in 1990.

‘Producer’s Showcase’ was NBC’s vehicle for their celebrated 90 minute color “spectaculars” which included 37 productions from 1954 till 1957. The most famous of these would be ‘Peter Pan’. This was the eleventh edition of this monthly series and may have been the first one done from the west coast.

It was directed by Delbert Mann and starred Bacall, Henry Fonda and Humphrey Bogart in what would also be his first appearance in a live television drama. Jack Klugman, Richard Jaeckel, and Jack Warden played supporting roles.

If you’ve ever seen “Key Largo”, you’ll instantly recognize the similarity of the story lines of escaped convicts taking over, in this case, a dessert dinner as opposed to a Florida Keys hotel. Enjoy and share. – Bobby Ellerbee

‘Your Hit Parade’…The Original, Music Countdown Show

On August 6, 2014

- TV History

‘Your Hit Parade’…The Original, Music Countdown Show

Long before the Casey Kasem or American Bandstand countdowns, there was ‘Your Hit Parade’ which started on radio in 1935 and ran there till 1955. The television version started on NBC in 1950 and ran there till ’58 when it went to CBS for a year.

In the great photo below, we see one of the show’s biggest stars, Dorothy Collins singing before the cameras at NBC’s Ziegfeld Theater, in color. The show started July 10, 1950 in NBC’s brand new Studio 6A which was converted May 29, 1950.

The show needed more floor space for the 10 song scene sets and the next year it moved to NBC’s brand new 8H which was converted January 30, 1950. The show was done in color occasionally from The Colonial Theater, but went all color in 1956 when it moved to Perry Como’s new home at the Ziegfeld Theater.

You can tell from the look of this video clip that this was a color broadcast captured on black and white kinescope film. It shows Dorothy Collins singing “I Get A Kick Out Of You” from the Ziegfeld. When the show moved to CBS, it went back to black and white. Enjoy and share!

Behind The ‘Laugh In’ Joke Wall, Photo & Video

On July 14, 2014

- TV History

Ultra Rare…Behind The ‘Laugh In’ Joke Wall, Photo & Video

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=cFksUB9gWyk

First, there is an “extra special” blooper at the 1:30 mark of this great ‘Laugh In’ joke wall blooper reel. By the way, the first person you see is Producer George Schlatter, with the bead.

This is the only known photo of this famous ending portion of the show that gives us a look at how it was staged. I think ‘Laugh In’ came from NBC Burbank Studio 3, but over the years, could have been done in more than one location there.

Although this was a color show, notice the blooper reel is in black and white and here’s why. This was one of the first weekly shows to be shot and edited on color videotape, but it was still a hand splicing task back then. The best way to edit the show was to also make a kinescope of the live taping and first, edit the kine film. The cuts were very fast and it took the editors about five or six weeks to get each episode ready for air. Enjoy and share!

The NBC 8G Studio Cameras…One Of Television’s Rarities

On July 12, 2014

- TV History

The NBC 8G Studio Cameras…One Of Television’s Rarities

NBC’s official grand opening date for 8G, their second ever studio at 30 Rockefeller Plaza is listed as April 22, 1948. Actually, television had been coming from 8G long before that while it was still designated a radio studio.

The first show ever to come from 8G was also television’s first variety show…’Hourglass’, which debuted May 9, 1946. Later that year, ‘Let’s Celebrate’ was done here as a one time show on December 15, 1946 with Yankee’s announcer Mel Allen as host.

‘The Swift Show’ (a Swift Company sponsored game show), and ‘Americana’ (a game show about American history) started here in 1947.

With the RCA TK30 planned release date of late 1946, I have often wondered why the NBC engineers built these cameras to use in 8G but recent research put a new face on this and answers a few big questions.

NBC knew television had to grow fast after WW II, but there were still war related shortages, like phosphorus for kinescope screens and military embargos on technology like the Image Orthicon which was used in guidance systems. Believing that new cameras would come more slowly than RCA was planning on delivery, NBC engineers knew they had to have more than the cameras in 3H to work with. On the sly, the got four RCA Image Orthicons and four seven inch kinescopes for the VF and started to work building a camera I call the NBC ND-8G. The ND was an NBC engineering code that stood for New Development.

I think these cameras were actually ready for use by the spring of 1946. ‘Hourglass’ debuted from 8G on May 9, 1946 which was six months before the TK30 scheduled release in October. NBC got their first four TK30s in late June, just in time for the Billy Conn – Joe Louis rematch at Yankee Stadium.

I don’t think 8G, as a radio studio, had built in audience seating like 6A, 6B and 8H, but it was thankfully three times the size of NBC’s only other television studio, 3H. “Radio Age” states that 8G could handle four consecutive shows, which meant the often fifteen minute and half hour shows, with only one small set, could be staged one after the other from different walls of the studio.

Below we see the cameras in action on ‘The Philco Television Playhouse’ which originated in 8G beginning in October of 1948. Notice the camera peephole in the wall covered by a painting. Enjoy and share!

The 14 City NBC Television Network…1949

On July 9, 2014

- TV History

The 14 City NBC Television Network…1949

From the ‘Howdy Doody Show’, we get some interesting information on the status of NBC’s coverage of the country via the AT&T links for live television. This show was kinescoped and mailed to most of the other major metro areas not covered by the growing network.

My home town of Atlanta was added on October 4, 1950, just 27 days before I was born.

Here’s A Rare Sight & Great DGA Article…’I Love Lucy’

On June 30, 2014

- Archives, TV History

This is a fascinating article from Ted Elrick in “The Director’s Guild Of America Quarterly” on how the show was done. There is a lot of information there you won’t read anywhere else. The whole article is copied below.

http://www.dga.org/Craft/DGAQ/All-Articles/0307-July-2003/I-Love-Lucy.aspx

In the photo, we see Desi Arnaz with Jess Oppenheimer looking at a control booth under construction at General Services studio just before the show started production. This is probably around August of 1951.

Now this is really more of an audio and intercom center than anything else, because as you remember the show was shot on film, but coordination was still a key factor in the production. All the camera, dolly and boom people wore headphones. I would think there was an assistant director in the booth reminding them of cues and the DOP and director would be on the studio floor. Enjoy and share!

I Love Lucy

Directing the first multi-camera film sitcom before a live audience.

BY TED ELRICK

Desi Arnaz and Lucille Ball in I Love Lucy

On October 15, 1951, television broadcast history was made when the first episode of I Love Lucy aired on CBS. Technically, it was not the first episode of the show. The pilot, directed by Ralph Levy, was recorded as a kinescope, a 16mm filmed recording taken from an extremely bright cathode ray tube, but it was not broadcast until 1990. Kinescopes are fuzzy and often distorted, but were the only means for communities outside of the reach of coaxial cable linked network affiliates, predominately on the East Coast where most television programs originated, to see network programming. Lucy was the first multi-camera sitcom to be filmed before a live studio audience.

Its genesis was really something of a fluke, primarily driven by a cigarette manufacturer’s objection to kinescope films. When I interviewed him in the late 1970s, Desi Arnaz said that CBS and the show’s sponsor, Philip Morris, objected to making I Love Lucy in Los Angeles. The sponsor in particular didn’t want the lucrative New York and East Coast market, accustomed to quality broadcasts, seeing their show the way the rest of the country saw other shows, on kinescopes.

Lucille Ball and Desi Arnaz were adamant that this production stay in Los Angeles, where they had made their home for several years. A compromise to “film” Lucy was reached after the network’s complaints about the increased costs of shooting in that medium were offset by Arnaz and Ball agreeing to take a cut in their weekly salary. In return for this salary concession, CBS agreed that Arnaz and Ball would own the shows after they were broadcast. Both were truly surprised by CBS’ concession. That move alone would eventually make Desilu Productions one of the most powerful independent companies in television.

However, the problem remained of how to film the show. Many cinematographers said it was impossible to film multi-camera before a live audience. Different lighting requirements were needed for master shots, medium shots and close-ups. It just couldn’t be done. But that was not a phrase in Arnaz’ vocabulary.

He called veteran cinematographer Karl Freund, then in his early sixties, who told Arnaz the same, “It can’t be done.” According to Stefan Kanfer’s new book, Ball of Fire, The Tumultuous Life and Comic Art of Lucille Ball, Arnaz replied, “Well, I know that nobody has done it up to now, but I figured that if there was anybody in the world who could do it, it would be Karl Freund.” Needless to say, flattery got Arnaz everywhere, and Freund set to work, eventually accomplishing what couldn’t be done.

Film considerably raised the bar on broadcast quality. Suddenly, people across the country all saw the same image, and they liked it. I Love Lucy was a hit.

Live Audience and Directing

In his book, And the Show Goes On, television pioneer Sheldon Leonard wrote about another of Arnaz’ decisions: “Operating on the well-founded belief that a comedy show needs an audience to give it the authentic response that canned laughter can never duplicate, Desi brought in an audience to watch and react, while he used multiple-camera shooting technique borrowed from live TV.”

Arnaz also “borrowed from live TV” director Marc Daniels who would sit in the director’s chair for the filmed I Love Lucy. Daniels’ contribution to choreographing three-camera technique was considerable and influenced generations of television directors.

James Nicholson, William Asher and William Quine on the backlot at Columbia Pictures.

Daniels would direct all of the first season’s 35 episodes, a season uninterrupted by today’s all-too-common reruns. In the DGA Oral History, The Days of Live edited by Ira Skutch, Daniels said, “I’d had the multiple-camera experience. [Lucy] was similar to live, except that the film cameras were much less flexible than the television cameras. You were stuck with the side cameras being the long lenses for close-ups and the center camera being the master camera, and you couldn’t change a lens as quickly.

“We began I Love Lucy using four cameras because they wanted to do the entire first half of the show without stopping,” Daniels continued. “We had four Fearless dollies, four dolly grips, four camera assistants, two booms, two dolly grips for the booms, and a few cable men. You can imagine what that floor looked like.”

After the first season, Daniels moved on to direct other shows. William Asher, who would later produce 285 episodes, and direct 200 episodes himself of another television classic, Bewitched, came on board, becoming the directing mainstay for many years, and further refined and perfected multi-camera technique.

Trouble on Day One

Asher’s first day on the set though nearly ended his association with the show. They had begun rehearsal and Asher had to walk away for a bit to attend to some technical matters. When he returned, he discovered that Lucille Ball had been giving directions backstage. Asher was astonished.

“I said, ‘Lucy, there’s only one director. I’m it. If you would like to direct, then don’t pay me and send me home,’ ” Asher said. “When I said that, she began to cry and ran off the stage. Everybody disappeared. Desi hadn’t been in the scene. I didn’t know where to go because I had no office. So, I went to the men’s bathroom, sat on the toilet and didn’t know what the hell to do. I realized I’d blown my first day of what was really a pretty good job.

“I sat there for a long time and finally got up and went back to the stage,” he continued. “Desi was there. He was furious. He was cussing me out in Spanish and I didn’t know what he was saying. I settled him down and said, ‘Look, Desi, here’s what happened.’ And he said, ‘Well, you’re absolutely right, Bill. What you should do is go in to Lucy’s dressing room. She’s crying. Go talk to her and settle this thing.’ So that’s what I did. I went in. I said I was sorry I upset her. And she was crying and I started to cry. And after a while we went back to work. But I’ll tell you this. I never had trouble from her after that. She had her opinion, and would offer it, but nothing ever behind my back. Everything was just fine. That’s the way it was for the next five years.”

On the set of I Love Lucy with Lucille Ball and William Asher

Scripts, Rehearsals and Showtime Folks

Asher said they began working on each season of Lucy with between six and seven scripts that were in very good shape. “The scripts were excellent,” Asher recalled. “We had only the producer [and head writer], Jess Oppenheimer, and two other writers who wrote as a team [Madelyn Pugh and Bob Carroll, Jr.]. And that’s all we had. Today you see 9, 10, or more writers.” Oppenheimer, Pugh and Carroll had also been the writing team of Ball’s hit radio comedy My Favorite Husband. In Lucy’s later years Bob Schiller and Bob Weiskopf would write episodes.

Asher said there was very little ad libbing because the material was strong and they’d had time to rehearse. “On Monday morning we would read the material, discuss it and make changes. In the afternoon, I would start rehearsing and continue rehearsing Tuesday and Wednesday when the cameras came in. On Thursday, we’d rehearse again with cameras about half the day. Then we would do a dress rehearsal. Later that day, we’d do the show.”

Rehearsals were vital because they were shooting film. At the time there were no monitors for the director to see the image. The show’s quality depended on his ability to watch the floor and ensure that all cameras and actors hit their marks at the required moments. Precision was crucial, as nobody wanted to halt the performance in front of an audience. They rarely shot pick-ups, Asher said, and when they did it was usually for a guest star who forgot a line. Most shows were filmed in around thirty minutes.

“We had stops for Lucy’s big costume changes, but that was all,” Asher said. “I had a pretty strict rule on that. We didn’t stop for anything. We played it like a Broadway show. If an actor made a mistake or forgot a line or something like that, it was up to the other actor to get him out of it.”

(Top) Lucille Ball performs the famous “Vitameatvegamin” scene (Below) Lucille Ball, William Frawley, Vivian Vance and Desi Arnaz in a scene from I Love Lucy

Asher can recall only one time when the show came to a dead stop. “Lucy always had one moment where she’d get stuck. We’d put that line of dialogue on the back of a lamp or something where we knew she’d be working. Once, right in the middle of a scene she suddenly stopped. And she was the only one in the scene, alone in the living room. I waited and waited. She just was staring at something. Finally, I yelled ‘cut’ and ran down to the set and saw she was staring at the back of a lamp where we’d put her line. She said the line didn’t seem right to her. It turned out that the lamp we were using in that show broke after dress rehearsal, and the crew brought in another lamp that had a line from a previous show from the year before on it. We explained it to the audience and replaced it with the right line and went on. It was the only time we stopped.”

Yet Another Innovation

On Friday, Asher would cut the show with the editor, and on Monday, during lunch following the next show’s read through, he’d watch the prior week’s show with Arnaz who would give his comments.

The editing of I Love Lucy brought another major innovation to television. Arnaz said that when he first sat down to watch the film, he found it very confusing to look at only one camera’s footage on a Moviola. He asked why he couldn’t see the film from all three cameras at the same time. He was told that this was the only way — one camera’s film at a time. Arnaz pushed the issue and asked, “Why can’t you just stick three Moviolas together?” So the production team contacted Moviola’s president, Mark Serrurier, son of Iwan Serrurier who had created Moviola in 1924. A graduate of Caltech who oversaw the design of the dome and structural parts of the 200-inch Palomar Telescope, Serrurier developed a three-headed machine to speed up the editing process on Lucy.

Jay Sandrich, who would establish his own directing legacy on The Mary Tyler Moore Show, Soap and The Cosby Show, began his career as a 2nd AD on I Love Lucy. He moved up to 1st AD when Jack Aldworth moved up to producer. “I was 24 and I knew nothing,” Sandrich said. “I was learning on the number one show in the country. Aldworth was a wonderful mentor who really helped me.”

After thousands of reruns in syndication, it’s sometimes easy to forget just how innovative I Love Lucy was to the history of sitcoms. But it set the stage for further technical innovations, for influential independent producers like Sheldon Leonard, Norman Lear, and Grant Tinker, and for strong directors whose voice and commitment to the idea that “There can be only one director” would continue to perfect the uniquely American art form known as the sitcom.

A Real Rarity…’Amos ‘n’ Andy’ Television Screen Test, 1950

On June 29, 2014

- TV History

A Real Rarity…’Amos ‘n’ Andy’ Television Screen Test, 1950

Before ‘Amos ‘n’ Andy’ came to CBS Television in 1951, it had been a huge hit on radio and aired from March 19, 1928 to November 25, 1960. Charles Correll (Andy), and Freeman Gosden (Amos and Kingfish) were the creators and voices of all the characters…170 of them.

The rare video here is a 1950 kinescope recording of a screen test

of Correll and Gosden in blackface. In the last few minutes of the reel, you can see them giving different profiles to the camera to see if they are convincing, which they are not. This was probably done at CBS Columbia Square studios in Hollywood.

Gosden and Correll were very protective of their creation and wanted to play the roles on TV, but that was not in the cards. They even considered voicing the main characters and letting the stage actors lip sync their parts.

In their hearts, they knew that a couple of white guys could not pull this off on television, but they gave it a try. Fortunately they had been smart enough to keep an eye out for the right characters to play the TV roles and had been taking notes on actors for four years.

Alvin Childress was cast as Amos, who was the original main character in 1928, but by the late ’30s, the Kingfish character had become the main character, along with Andy. Tim Moore, who played Kingfish and Spencer Williams who played Andy were coaxed out of retirement to play the lead rolls.

There were a few “firsts” associated with this show’s radio and television history. ‘Amos ‘n’ Andy’ is thought to be the first ever syndicated radio show: although it was broadcast on NBC for many years, it was also sold to independent stations and delivered on 78 rpm discs. The television show went into production at Hal Roach Studios and began filming with three cameras several months before ‘I Love Lucy’ began filming and is considered one of the first sit coms to be filmed with three cameras. ‘Burns & Allen’ also did this, but live television had been doing three camera shows for years.

CBS, NBC First West Coast Homes (With Video)

On June 28, 2014

- TV History

CBS, NBC First West Coast Homes (With Video)

Before there was Television City and NBC Color City, there was CBS Columbia Square and NBC Radio City West. Both were originally built for radio and about a third of their radio shows came from Hollywood.

Columbia Square opened in April 1938 and television came there in 1948. The first network television show to originate from the west coast was ‘The Ed Wynn Show’ which came from Studio A…the same stage that would later be used to kinescope the pilot of ‘I Love Lucy’.

At the link is the Saturday, March 25, 1950 broadcast of ‘The Ed Wynn Show’, (a/k/a Camel Comedy Caravan) with The Three Stooges. The show was done live on the west coast at 9 PM and shown on the east coast, the next Saturday as 9 Eastern via kinescope.

Television came to NBC’s Radio City West in January of 1949 when KNBH was launched. NBC’s Hollywood studios opened in 1938 and served as a replacement for NBC’s radio broadcast center in San Francisco, which had been around since the network’s formation in 1927. Since NBC didn’t own a radio station in Los Angeles, the network’s West Coast programming originated from its San Francisco station (KPO-AM, which later became KNBC-AM, and is now KNBR).

A Half Hour Behind The Scenes Of Television…January 1952

On June 24, 2014

- TV History, Viewseum

A Half Hour Behind The Scenes Of Television…January 1952

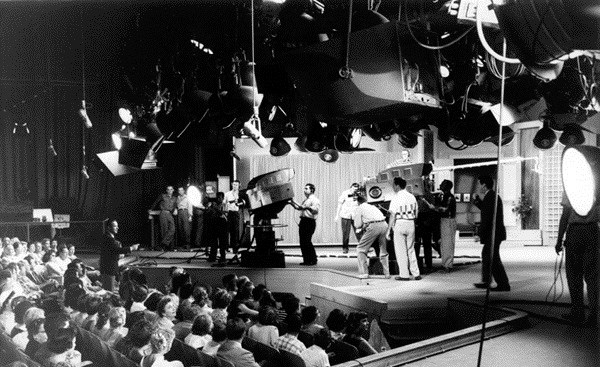

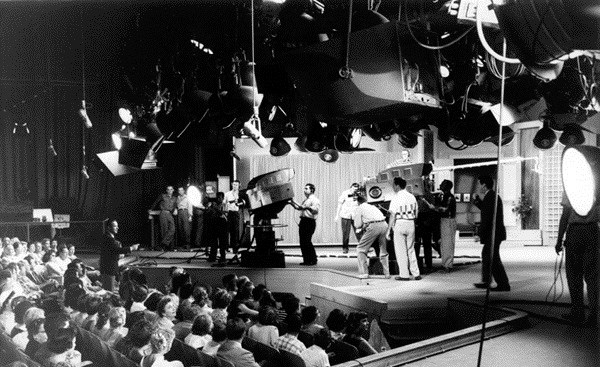

If you ever wondered how different, or the same, television production was back in the ’50s, here’s your chance to find out. This is a very thorough look at how ‘The John Hopkins Science Review’ program was done at Baltimore’s WAAM.

The tour starts in the control room with ample demonstrations and moves to the studio where RCA TK30s are capturing the scenes we see now on this kinescope recording. This is an early DuMont program and was originally shown on January 7, 1952.

‘All In The Family’…Some Interesting History

On June 13, 2014

- TV History

‘All In The Family’…Some Interesting History

Well, these pictures of the cast arriving at Television City settles one thing…it was definitely after September of 1973 when the set moved to Metro Media Studios. I can’t find a firm date, but I think the show moved at the end of the 1975 season.

I understand the reason for the move was that Norman Lear had so many shows in production at NBC, CBS and ABC, that shuttling between the shows was driving him crazy. Metro Media heard about this and offered Lear all seven stages of their Metro Media Square facility and he took them up on the offer and moved them all under one roof.

I’m not sure if this is true, but it is widely reported that when the show’s first pilot was done in New York in 1968, it became the first time a sitcom in the US used videotape as a recording device. Most sitcoms were either done on film or were performed live and kinescoped. Videotape editing was still done with a razor blade and Smith Block back then.

Did you know that Harrison Ford was offered the part played by Rob Reiner? Or that Reiner had to audition three times before Lear chose him? By the way…”Meathead” was the name Lear’s father called him when he was upset with him.

When CBS started rerunning the show during the day in 1975, it was edited by three minutes to allow more commercial time. Norman Lear was unhappy with the editing and offered to pay for the commercial time that would have been lost by showing it uncut, but CBS declined his offer. That I know of, this is the first mention of 7 minutes of spots in half hour show. 4 minutes was the prime time rule.

Although Edith Bunker’s singing voice left a lot to be desired, Jean Stapleton’s didn’t. She was classically trained and had many singing parts on Broadway.

‘The Honeymooners’…The Classic 39

On June 12, 2014

- TV History

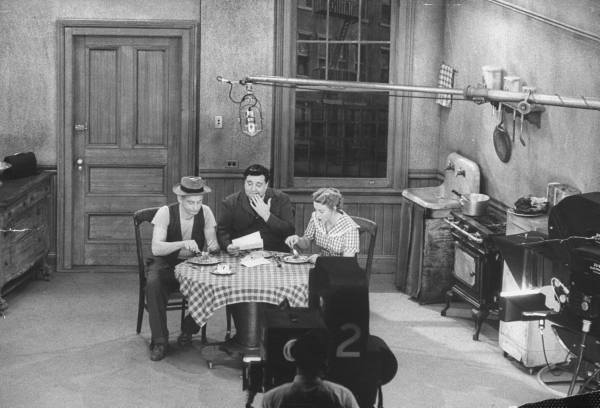

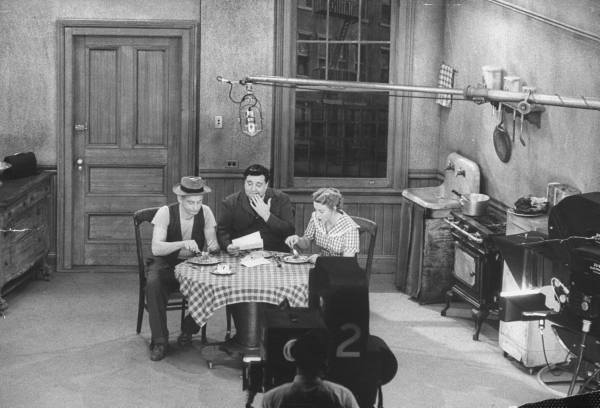

‘The Honeymooners’…The Classic 39

The first Honeymooners sketch was done live, October 5, 1951 as part of Dumont’s ‘Cavalcade Of Stars’ show which Jackie Gleason had become the host of in June 1950. It was only six minutes long, but started something that lasts till this day.

Gleason’s Dumont show did quite well and CBS noticed! They brought Jackie and company to Studio 50 in July of 1952 and the rating soared on the Saturday night, hour long, live broadcast. As Honeymooners sketches became more popular, they got longer and could run up to 30 or 45 minutes.

In 1955, Gleason told CBS he wanted take a break from the live show, but wanted to continue a half hour version of the Honeymooners. Gleason still had friends at Dumont and they had told him about the new Dumont Labs Electronicam that shot live video and 35 millimeter film simultaneously.

Gleason had been impressed by the way ‘I Love Lucy’ was produced and wanted to do film, but keep the live aspect of the show. The Electronicam was perfect for this. A kinescope recording was made of the live presentation, which was switched like a regular live show, but in editing, if a camera had a better angle on a scene, they were able to use that instead of the original shot.

All 39 episodes of The Honeymooners were filmed at the DuMont Television Network’s Adelphi Theater at 152 West 54th Street in Manhattan, in front of an audience of 1,000. Episodes were never fully rehearsed, as Gleason felt that rehearsals would rob the show of its spontaneity. The shows were shot on Saturday nights at 8 and by 9, Jackie was headed to Toots Shores or 21.

Gleason and company went back to live television in 1956 because Jackie felt the quality of the longer Honeymooners scripts was petering out. The 39th and last original episode aired on September 22, 1956. In explaining his decision to end the show, Gleason said, “the excellence of the material could not be maintained, and I had too much fondness for the show to cheapen it”. One week after The Honeymooners ended, ‘The Jackie Gleason Show’ returned live to Studio 50 on September 29. Soon after, so did The Honeymooners sketches. Enjoy and share.

‘The Bob Crosby Show’…CBS Daytime, 1953-1957

On June 11, 2014

- TV History

‘The Bob Crosby Show’…CBS Daytime, 1953-1957

In the photos, we see RCA TK40s and 41s on the Crosby Show which was done Monday thru Friday from Television City’s Studio 33. Like most TVC shows, it was usually done in black and white, but every couple of months or so, they would broadcast a day or two, or a week in color. Studio 43 was equipped with RCA TK40A color cameras in 1954, with cables allowing any of the original four studios to use those cameras. In 1956, Studio 41 was equipped with RCA TK41s.

Jack Narz was usually the announcer for the show, but in the clip and the photo, we see different announcers. That’s Tom Kennedy in the photo with Crosby, but I don’t recognize the announcer in the video.

I think this show aired between 1 and 3 PM in the east, but since this is in the pre videotape days, it had to be done live in LA in the morning and was kinescoped for the west coast playback. Here is a sample:

The attached show clip was done in ’53. These are the other shows that were being done live from Television City that month, and the studios they came from.

ART LINKLETTER’S HOUSE PARTY 41

LIFE WITH FATHER 43

LUX VIDEO THEATER 43

MEET MILLIE 31

MEL ALLEN 31

MY FAVORITE HUSBAND 33

MY FRIEND IRMA 31

PLACE THE FACE 41

RADIO & RECORDS EVENT 31

THAT’S MY BOY 33

THE BOB CROSBY SHOW 33

THE RED SKELTON SHOW 31