- Home

- TV History

- Network Studios History

- Cameras

- Archives

- Viewseum

- About / Comments

Skip to content

Search Results for: kinescope

Historically Speaking…History Of Editing

On July 19, 2013

- TV History

Historically Speaking…

This is a very interesting history of the way television shows were broadcast and recorded first to Kinescopes and later to videotape and how they were edited. Did you know ‘Laugh In’ episodes took over 50 hours to edit? This take us all the way up to Avid systems.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=TIVYeyWHajE

Trace the history of modern day film editing – starting with electronic engineers developing solutions for capturing and editing television through to the fi…

Network Notes…On October 4, 1950, Atlanta Gets Coax Connection

On March 12, 2013

- TV History

Network Notes…

On October 4, 1950, Atlanta was finally able to bring live network shows to Georgia via the new coaxial cable. Before the AT&T connection, network shows came in the mail as kinescopes and films.

The Hollywood Palace

On February 24, 2013

- TV History

‘Hollywood Palace’: History

This is an excellent history of the show from TV.com. Enjoy!

The Hollywood Palace was an hour-long variety show that ran on the ABC-TV network from January 4, 1964 to February 7, 1970. Instead of a permanent host, guest hosts were used. Bing Crosby, a frequent guest host, hosted the first and last Hollywood Palace shows. Four of Bing’s Christmas specials, featuring his wife Kathryn and their 3 children, were actually Hollywood Palace shows.

The Hollywood Palace was a mid-season replacement for “The Jerry Lewis Show.” ABC originally had high hopes for Lewis’ live, two-hour variety series. They signed the comedian to a 5-year contract for a reported $35 million. The network also purchased the El Capitan Theater in Los Angeles and re-christened it “The Jerry Lewis Theater.” “The Jerry Lewis Show” premiered on September 21, 1963, but by Thanksgiving 1963 it was apparent that the show was a failure. ABC decided to replace it with a variety show. The network hired Nick Vanoff to produce the new show. Vanoff, in turn, hired William O. Harbach and Otto Harback to help him develop the series. They hurriedly came up with the concept of Hollywood Palace.

The final “Jerry Lewis Show” aired on December 21, 1963, and The Hollywood Palace premiered on January 4, 1964. (ABC aired a special on 12/28/63.) The Hollywood Palace took over the first hour of Lewis’ old time slot. The second hour was given to the local affiliates for their own local and syndicated programming. The old “El Capitan Theater” was once again re-named, this time as “The Hollywood Palace.”

The Hollywood Palace resembled a Vaudeville show. Raquel Welch, who was just a few years away from international stardom, was a regular on the 1964 shows. Welch appeared as the “billboard girl,” who changed the large cards that introduced the guests. The first 2 seasons of The Hollywood Palace were in black and white.

The Hollywood Palace switched to color at the start of its third season. The first color episode was broadcast on September 18, 1965. The “Hollywood Palace” theater became ABC’s first color videotape studio. It was also the home of “The Lawrence Welk Show,” which switched to color in the same month.

Collectors of this series may notice that black and white copies of the color episodes are available on VHS. These copies were mastered from B&W 16mm kinescopes. (Kinescopes were a videotape-to-film transfer produced by aiming a 16mm film camera at a TV monitor.) The original color videotapes do exist but they are not as accessible as the b/w kinescopes. These 16mm kinescopes were originally used by local U.S. stations and by the AFRTS. In the 1960’s, many local stations in smaller markets carried more than one network. And often it was the ABC programs that were bumped to other time slots. Instead of purchasing the then-expensive video tape recorders for time-shifting purposes, the stations opted to use 16mm kinescopes provided by the network. Kinescopes were also used by the AFRTS which operates TV stations on overseas military bases. The AFRTS prints usually do not have the original network commercials.

The Hollywood Palace Broadcast days/times Seasons 1 through 4 – Saturdays 9:30pm Eastern Season 5 (1967-68) Tuesdays 10:00pm Eastern (through 2-Jan-68) Season 5 – Saturdays 9:30pm Eastern (13-Jan-68 through end of season) Seasons 6 & 7 – Saturdays 9:30pm Eastern.

Ralph Levy: Director Extraordinaire

On February 20, 2013

- TV History

Ralph Levy: Director Extraordinaire

Ralph Levy, TV pioneer and two-time Emmy winning director, is remembered by TV historians as the man who directed the original ‘I Love Lucy’ pilot in March, 1951 — which made his passing on the date of Lucy’s 50th Anniversary all the more poignant.

Born into a family of Philadelphia lawyers, Ralph was stage-struck from an early age. Bowing to family pressures, he earned a degree from Yale University, from which he was graduated just in time to serve in the Army during World War II.

Television was then in its embryonic development stage in New York City, and Levy landed a job of assistant director at CBS. Early assignments included covering sporting events such as boxing, basketball and professional football games. If nothing else, the apprenticeship allowed him to learn all about the cameras, lenses, lights and other new video technology. Ralph was never shy about his interest in musical comedy, and within a few months CBS gave him a chance to switch from sports to entertainment. They assigned him to work on the television edition of ‘Winner Take All’, a question-and-answer quiz program that had proven very popular on CBS Radio.

In early May of 1949, Ralph was asked to direct a variety show called The 54th Street Revue. Ralph managed to get the first of the shows on the air in only 4 days — an accomplishment that earned him both management’s attention and a reputation for working swiftly and efficiently.

That fall, CBS asked Levy to move to Los Angeles to direct a new variety series starring famed radio comedian Ed Wynn. If network TV in New York was just beginning, in Los Angeles it was virtually non-existent…

The Ed Wynn Show, Levy soon discovered, would be the first major network show on CBS to originate from Hollywood. It would be shown “live” on the West Coast every Thursday night at 9PM. A kinescope recording of the show would be made, sent to New York, and played for East Coast and Midwestern stations two weeks later. Such delays were necessary because the transcontinental cable was not yet in place that would allow for national live telecasts to originate on the West Coast.

The Ed Wynn Show premiered on October 6, 1949, and almost immediately ran into a talent booking problem. Big-name movie performers wanted nothing to do with the new video medium. Wynn started booking talent from the recording industry (Dinah Shore), old friends (Buster Keaton) and stars from network radio. In late December, Ed’s guests were Lucille Ball and Desi Arnaz.

“This was one of the first times I ever did anything on TV,” Lucy recalled later. “So frightening, but so wonderful. I’d never been in such a hurried, chaotic setting with these monstrous television cameras all over the stage and not enough rehearsal. But it was great fun.”

The script that night went out of its way to spotlight 32-year-old Desi, who appeared with Wynn and Ball in a comedy sketch, and even afforded him the opportunity to sing “Babalu.”

A few weeks later, CBS asked Lucy to consider transferring her radio series, ‘My Favorite Husband’, to TV. They wanted her — but did not know how her Latin husband would fit in.

Levy, meanwhile, had come to be the network’s fair-haired boy in Hollywood… In April, he expanded his duties to include directing the new Alan Young Show, a weekly half-hour comedy-variety skein starring the young Canadian who today is more remembered for his role ten years later in the sitcom Mr. Ed.

One of the most successful programs on CBS Radio that season was ‘You Bet Your Life’, starring the irrepressible Groucho Marx. The show’s sponsor, DeSoto-Plymouth Automobiles, was interested in adding a TV version — and both CBS and NBC wanted to carry it. Groucho later recalled, “You Bet Your Life shot up to Number 6 in the ratings. When both major networks — NBC and CBS — approached us about going on television, a bidding war started. Since we were already at CBS, it seemed likely we’d stay there. One of their star directors, Ralph Levy, helped us with the pilot show. When the dust settled, NBC was the high bidder. Levy stayed at CBS…”

The Ed Wynn Show ended its nine-month run on July 4, 1950, and Ralph headed to Mexico for a much-needed vacation. He had hardly unpacked when an emergency call came from Harry Ackerman, head of CBS’ Hollywood operations. “He asked me to come back the next day,” Ralph remembered later. “George Burns and Gracie Allen had agreed to go on television, and Harry wanted me at the first production meeting.” So much for Levy’s vacation…

A pilot was prepared and quickly sold to Carnation Milk Company, and ‘The George Burns – Gracie Allen Show’ was scheduled for a fall premiere. George was afraid to take on a weekly show all at once, particularly one that was to be done “live,” so CBS agreed to air it on an alternate-week basis. Complicating matters, especially for Ralph, was the fact that the network wanted to do the first 6 shows from New York. (The show could get better media coverage there, the network reasoned.) The cast and crew were sent to New York, and Ralph became bi-coastal for three months.

Making his life even more interesting was the fact that George Burns’ best friend, Jack Benny, was toying with the idea of getting into television himself. Naturally, he wanted Ralph to direct. But Benny was even more shy about TV than George and Gracie, and agreed to do only four half-hour specials that first 1950-51 season.

Lucy and Desi Arnaz, meanwhile, spent the summer of 1950 performing a comedy act in vaudeville theatres across the country, and by late fall had convinced CBS to let them try a new TV series together. Lucy’s radio writers — Jess Oppenheimer, Bob Carroll Jr., and Madelyn Pugh — went to work to create the format. Ralph Levy was asked to direct.

“I was anxious to direct Lucy’s pilot because I had worked with her on The Ed Wynn Show,” Levy recalled later. “I remember that the script called for Lucy to parade around the living room with a lamp shade on her head — trying to prove to Desi she could be a Ziegfeld Girl. I didn’t think she was walking the right way, so I showed her how it should be done — not knowing that she had been a showgirl for many years. Instead of telling me off, she simply played along with me. She was so professional and so good. She walked away with the whole show.”

The pilot was filmed on Friday evening, March 2, 1951 (Desi’s 34th birthday) in Studio A of CBS’ Columbia Square headquarters in Hollywood. It was the same stage used for the Wynn Show a year earlier. “There were only two sets,” Lucy recalled. “One was a living room and the other the nightclub where Desi worked. The show was shot live with a studio audience in attendance, as most TV shows were being done then. There was no tape yet. The images were recorded on film from a TV screen, providing us with the required kinescope.”

By the end of April the Lucy series, now titled ‘I Love Lucy’ had sold to CBS and Philip Morris — neither of which wanted the actual series to be done like the pilot (and the Wynn Show) via kinescope. The Arnazes balked at moving to the East to do the show live out of New York, so plans were set in motion to have the show filmed in Los Angeles using 35mm film. Levy, CBS’s first choice to direct, begged off: he knew he already had his hands full directing the Alan Young and Burns ‘n’ Allen series (plus the Jack Benny specials!). Levy also did several, live CBS ‘Playhouse 90’ presentations when his schedule allowed.

Interestingly, a year later, after ‘I Love Lucy’ proved a quality series could be done on film, Burns and Allen decided to do their shows on film, too (rather than “live”). Their company, McCadden Productions, moved onto the General Service Studio lot and became neighbors to Desilu and ‘I Love Lucy’. In 1953, Ralph retired from Burns ‘n’ Allen, and with The Alan Young Show ceasing production, he concentrated his energies on the now bi-weekly Jack Benny Program. He remained at Benny’s side another four seasons, then returned in 1959 to helm two hour long Benny specials. For these shows, he won his first Emmy Award.

Ralph won a second Emmy two years later for first Bob Newhart Show, a weekly half-hour of stand-up comedy and variety.

When filmed sitcoms became the order of the day, Levy adapted: he directed the pilots of ‘The Beverly Hillbillies’ and ‘Green Acres’, and two seasons of ‘Petticoat Junction’, all for his friend Paul Henning, one of George Burns’ writers who had since become a successful producer. (Petticoat, reunited him with actress Bea Benederet, who had been a regular on the Burns show.) Ralph later attempted to do dramas, programs like ‘Hawaii Five-O’, and feature films, but somehow, his heart was not in these projects: he missed the live audiences that early television and the theater had provided. The thrill of “opening night” was missing.

Levy spent several years in England in the 1970s, working for BBC Television, and taught TV production classes at Cal State Northridge and Loyola Marymount University.

Reflecting back on the various stellar performers with which he had worked, Ralph once observed, Groucho really was grouchy, probably because he “suffered from an inferiority complex.” Wynn was cerebral; Allen was always prepared, funny and “a doll” to work with. Ball was a top-notch clown, hard worker and tough business-woman. Benny, he always said, was the best of all, “a marvelous man.”

As for the new breed of television comedies, he found many of the shows to be too loud and vulgar for his taste. Working on modern shows “was not the same as working with Ed Wynn, or George and Gracie, or Jack. These people were from another era of show business; one in which you took literally years to build your comedic character… It’s very different today. The Burns and Allen show and Jack’s show were essentially one-man operations. Nowadays there are literally dozens of people grouped around TV shows, and to get a comedy idea past them, you have to run a gauntlet. And in those days we were enjoying our work. It’s not fun anymore. One guy’s there saying, ‘You’re going overtime,’ another guy’s there saying, ‘You’re over budget,’ everybody’s tensed up and nervous. Oh, sure we had plenty of our own crises, but they were usually constructive ones, based on doing the best possible show we were capable of.”

‘Westinghouse Studio One’, The Scarlet Letter: April 1950

On January 2, 2013

- TV History

‘Westinghouse Studio One’, The Scarlet Letter: April 1950

In 1948, ‘Westinghouse Studio One’ made a quantum leap from radio to television. The television series was seen on CBS from 1948 through 1958, under several variant titles: Studio One Summer Theater, Summer Theater, Westinghouse Studio One and Westinghouse Summer Theater.

CBS produced the show in New York and it was telecast live in the east, but a kinescope had to be shipped to LA for broadcast the next week until AT&T connected east and west in 1951. In later years, they moved the show to Television City as ‘Studio One From Hollywood’. Offering a wide range of dramas, Studio One received Emmy nominations every year from 1950 to 1958 and produced 466 memorable teleplays.

Dumont Electronicam TV-Film System

On December 24, 2012

- TV History

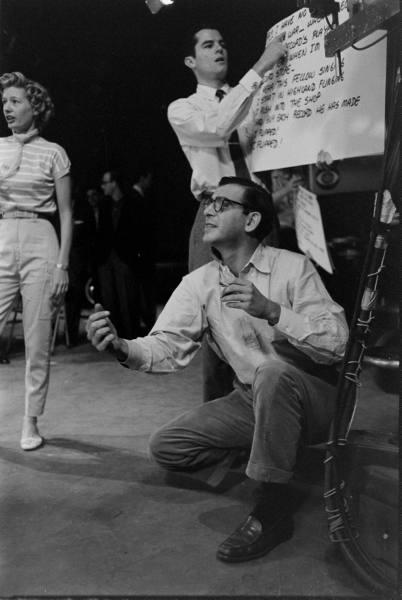

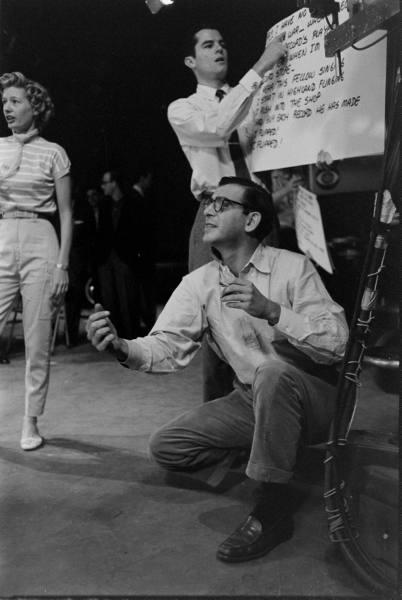

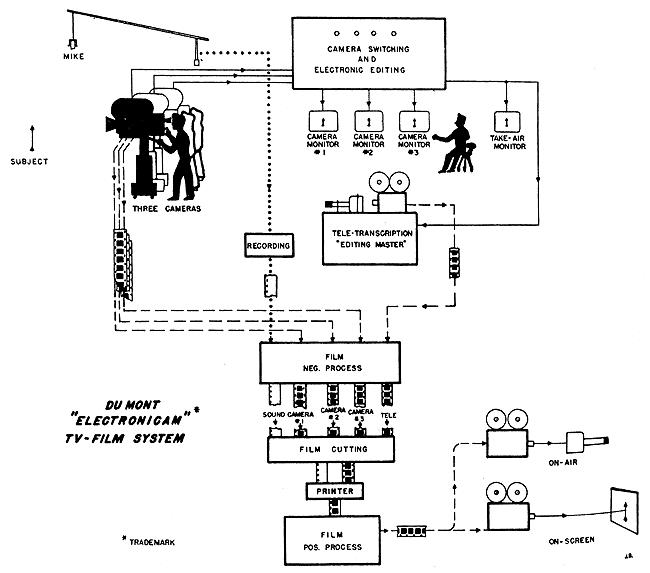

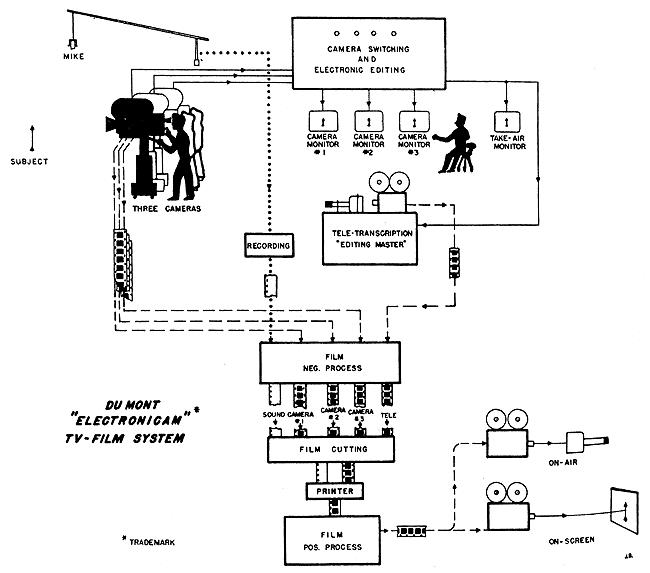

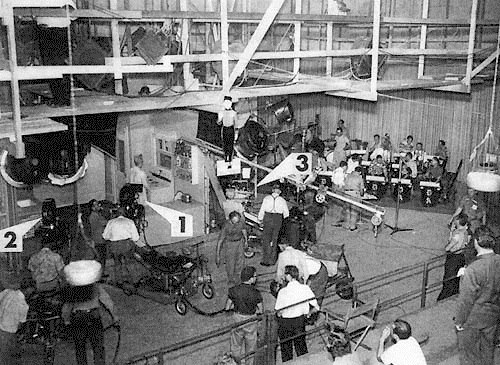

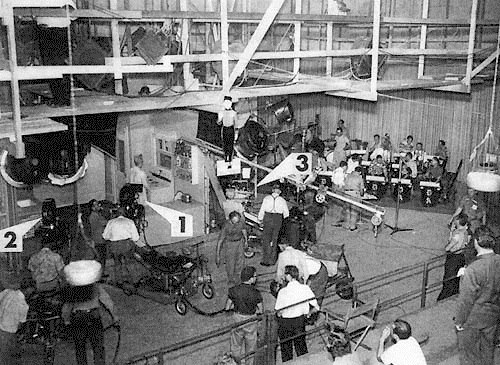

Dumont Electronicam TV-Film System

The more things change, the more they seem to stay the same. For instance, all the late night shows, be it Leno, Letterman, Conan or Fallon all have something in common with the way ‘The Honeymooners’ was done…individual recordings from each camera that allows for post editing to get the best shots for the final cut.

When ‘The Honeymooners’ was shot live in front of an audience, three Dumont Electrocams were shooting live video and filming in 35mm. A kinescope was made of the live show as a guide for film editing and in the final cut of the film, better shots could be chosen. It’s the same process with the late night shows, only now it’s all digital and a lot quicker in post.

What Does The ‘TK’ On RCA Cameras Stand For?

On December 14, 2012

- TV History

What Does The ‘TK’ On RCA Cameras Stand For?

As most of you know, the TK prefix on RCA camera models began in 1946 with the introduction of the RCA TK30 Image Orthicon camera. Pictured below is one of the very first TK30s delivered to NBC in early June of 1946.

Last night I had a conversation with my friend Lou Bazin who was the lead engineer on the TK44 and TK76 lines at RCA. I asked Lou what the ‘TK’ designation stood for. He said that he had asked the same question many years ago too. He said he never got a clear answer, BUT…it probably stands for Tele Kine.

That had never crossed my mind, but it’s actually a very good answer and here’s why. Over time, references change. For instance, ‘hooking up’ used to mean I’ll meet you later. Now it means having sex. Same for the word Kinescope which started as a noun, but later became a verb.

Before the process of recording the output of a cathode ray tube to film became known as a ‘kinescope’, the term originally referred to the cathode ray tube used in television receivers, and the word kinescope was coined by RCA’s Vladimir K. Zworykin.

As a noun, Kine is defined as: “a cathode-ray tube with a fluorescent screen on which an image is reproduced by a directed beam of electrons”. Tele is defined as: “across a distance”. Combine the two terms and you get the idea of a creation that can make images at a distance. That is in essence, the definition of a television camera.

I can see how, as a quiet tribute to Zworkin and RCA heritage, that the TK designation would be appropriate. The Image Orthicon tubes used in the first TK models, the TK30 and TK10, were revolutionary in their ability to shoot great pictures with much less light…even candle light.

This is as good an answer as I have ever heard, but like many things from that bygone era, we are not really sure of the truth.

The Man Who Filmed ‘I Love Lucy’, Tells Us How It Was Done.

On October 20, 2012

- TV History

The Man Who Filmed ‘I Love Lucy’, Tells Us How It Was Done.

By: KARL FREUND, Director of Photography

The Lucille Ball-Desi Arnaz show was a challenge from the start. It was decided that, for the first time, TV cameras would be replaced with three motion picture cameras to allow more flexibility in editing and to improve the photographic quality over kinescope recording.

This, I felt, was a legitimate approach to the situation. I expected very little variation from the ritual of photographing regular motion pictures — but I had not taken into consideration the unique problems involved. I was soon to be faced with them.

First of all, a live show requires an audience. This necessitated a regular studio sound stage equipped with bleachers to hold some 300 people. Above the stage a series of directional microphones and loud speakers had to be installed.

To give the audience a clear view of the program, and to allow the cameras total mobility without interference from floor cables, the lights for the sets had to be placed above the stage.

It became obvious almost at once that the overhead light placement was hardly flattering to the photographing of the performers. While the print value seemed up to par when projected in a studio projection room, they showed too much contrast when viewed over a closed TV circuit. Thus, we were faced with the fact that the greatest difference between standard motion pictures technique and TV films is the subject lighting contrast, which is required.

The immediate question was what method we should use to obtain the desired compression in the positive print. The solution was fairly simple. After careful survey, we selected a method that would involve no departure from standard practice in processing laboratory operations. That is, in exposing the original negative, use a subject lighting contrast considerable lower than that normally used for conventional black and white motion picture photography and process both the negative and print in the normal way.

It requires four days to line up each weekly show of “I Love Lucy” and “Our Miss Brooks.” Two of these days are for rehearsals. At the end of the second day the cameraman sees a run-through during which he can make notes and sketches of positions to be covered by the cameras and instructs the electrical crew as to where lights are to be placed. The last two days are occupied by rehearsals with cameras.

Since a show with audience participation must go on at a specified time, this schedule must be religiously adhered to by everyone concerned, including the cast. An hour and a half is the actual shooting time.

To film each show we use three BNC Mitchell cameras with T-stop calibrated lenses on dollies. The middle camera usually covers the long shot using 28mm. to 50mm. lenses. The two close-up cameras, 75 to 90 degrees apart from the center camera, are equipped with 3″ to 4″ lenses, depending on the requirements for coverage.

The only floor lights used are mounted on the bottom of each camera dolly and above each lens. They are controlled by dimmers.

There is a crew of four men to each camera: the cameraman, his assistant, a “grip” and a “cable man.” Unlike TV, where one man generally handles the camera movements and views the results immediately, this technique requires absolute coordination between members of the crew.

Every movement of each dolly is marked on the floor for every scene. And since all the movements of the camera are cued from the monitor box, the entire crew works from an intercom system.

As for myself, I utilize a two-circuit intercom. This allows me to talk separately to the monitor booth and the camera crew on one; the electricians handling the dimmers and the switchboard on the other.

Retakes, a standard procedure on the Hollywood scene, are not desirable in making TV films with audience participation. Dubbed-in laughs are artificial and, consequently, used only in emergencies. Close-ups, another routine step in standard film-making, were discarded since such glamour treatment stood out like a sore thumb.