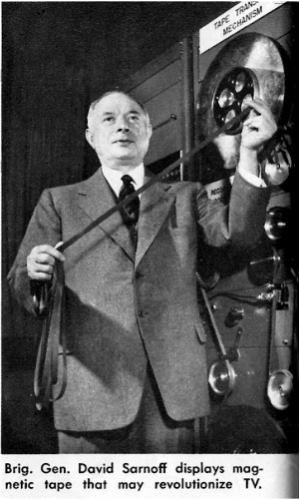

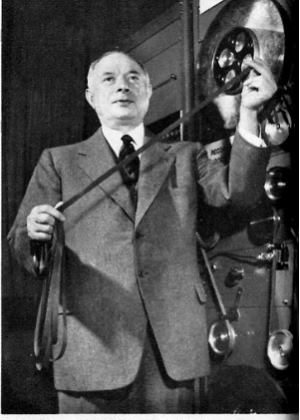

It was September 27, 1951, forty-five years since Sarnoff, at fifteen, had begged Guglielmo Marconi for a job at the wireless inventor’s American Marconi offices in New York City. To mark this anniversary, RCA’s R&D facility in Princeton, New Jersey, was being rechristened the David Sarnoff Research Center. In his luncheon speech the General ordered three gifts to be ready for his fiftieth anniversary, five years later: an electronic air conditioner, an electronic amplifier of light, and something he called the “videograph,” a “television picture recorder that would record the video signals of television on an inexpensive tape.” Sarnoff envisioned it as “a new instrument that could reproduce TV programs from tape at any time, in the home or elsewhere.”

Sarnoff expected these gifts to be produced in his namesake lab, of course. “But it is in the American spirit of competition that I call attention, publicly, to the need for these inventions,” he added. Over the next five years the General would often repeat his wish, never really believing that anyone but RCA could fulfill it. In fact, though, that third challenge sparked one of America’s great technology races.

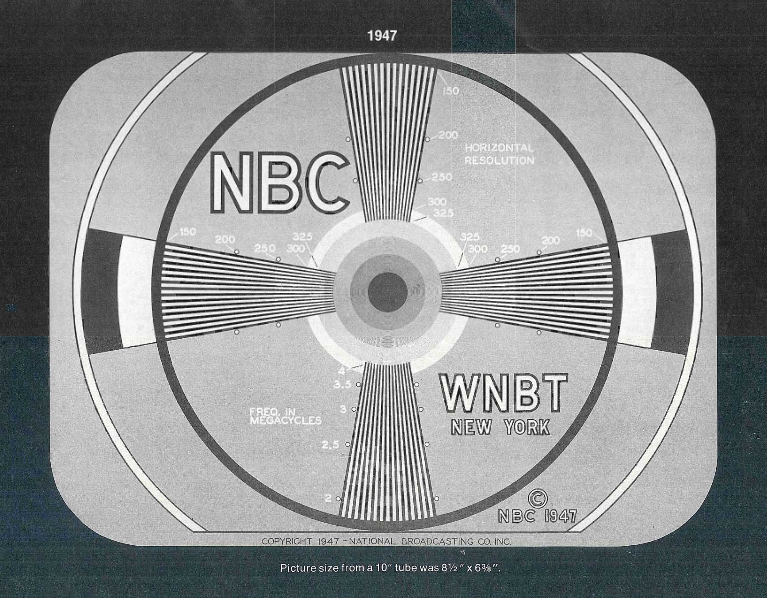

In the early 1950s no one imagined anything like Blockbuster Video. Television executives wanted a videotape system for much less ambitious reasons. Because of time-zone differences, programs had to be recorded while being broadcast live in the East for rebroadcast three hours later on the West Coast. Broadcasters had only one way to accomplish this time shift, a film process known as kinescope.

“Kines” (pronounced kinnies ), as they were known, were made by filming the picture off a high-resolution television set using a special synchronized 35-mm or 16-mm movie camera. The film then had to be processed as quickly as possible and rushed back to the studio for rebroadcast. Kinescopes, however, required a lot of time and labor. The picture quality was often poor because of the problems of synchronizing thirty-image-per-second television broadcasts with twenty-four-image-per-second movie equipment. On top of all this, kines were expensive; filming a half-hour show could cost as much as $4,000. By 1954 the American television networks were using more film than Hollywood. The broadcasting industry was desperate for a solution.

In principle the problem was not hard. If sound and light could be turned into electrical signals for broadcast, they could presumably be stored, just like any electric current, on a magnetic material. The first such medium, for sound recording, was magnetized steel wire. It had been demonstrated in 1900 by the Danish inventor Valdemar Poulsen and refined in the 1930s by Marvin Camras of the Armour Research Foundation (now the Illinois Institute of Technology), a research consortium of some 125 companies that could license any technology Armour came up with. Unfortunately, it was wholly inadequate for storing video. A typical visual image contains much more information than a sound recording, and thus television broadcasting—:and recording—requires an enormous range of frequencies. The leap from sound recording would be like the difference between a paper airplane and a moon rocket. But in the shadow of Edison, Einstein, and the atomic bomb, Sarnoff shared the popular notion of the time that science could accomplish anything.

The more capacious magnetic medium that was needed would probably be some sort of metal ribbon or tape. But no one had been able to perfect a magnetic recording tape—at least not in what was then the free world. In 1935, however, BASF (a subsidiary of the German chemical giant I. G. Farben) had developed a cellulose acetate-based tape coated with iron oxide particles for use in an audio recording device called the Magnetophon. The Magnetophon was manufactured by AEG, Germany’s General Electric. World War II kept this development hidden from American and British engineers, but the fledgling television industry discovered magnetic tape at the end of the war thanks to an Army Signal Corps major named Jack Mullin and a determined singing star who wanted to be able to tape his weekly radio show—Bing Crosby (see sidebar on page 58).

Mullin had graduated from the University of Santa Clara with a B.S. in electrical engineering in 1937 and worked for Pacific Telephone & Telegraph in San Francisco until the United States entered the war. Mullin served with the Signal Corps in England, then was sent to the Continent as the war in Europe ended. While searching a Radio Frankfurt studio, Mullin discovered a Magnetophon studio model R22A. The machine used BASF’s acetate-based recording tape coated with red iron oxide particles and yielded far better sound fidelity than any other recording medium. Mullin took two Magnetophons apart and mailed the pieces, along with fifty reels of tape, to San Francisco in thirty-five small packets. When he got home, Mullin reassembled and modified the Magnetophons and on May 16, 1946, unveiled audio tape recording to his stunned peers at the Institute of Radio Engineers convention in San Francisco.

Crosby signed Mullin up as chief engineer of Bing Crosby Enterprises (BCE), but he wasn’t the only one interested in the Magnetophon. A twohundred-employee company in Redwood City, California, called Ampex, founded in 1944 to make motors for airborne radar sets, was trying to shift from defense to civilian industry. Working with Mullin as a consultant, Ampex produced the first American commercial audiotape recorder, the Model 200, in April 1948. By August the Ampex machines, using a new kind of tape developed by 3M, had replaced Mullin’s rebuilt Magnetophons on the Crosby show.

The introduction of magnetic tape recording sparked a revolution in the broadcasting industry. When the excitement reached Marvin Camras, who had perfected wire recording almost a decade earlier, he began his own research into video recording using 3M’s new magnetic tape. To record the much wider video signal, Camras would have to speed up the tape from 15 inches per second (ips), the standard for sound recording, to 300 or 400 ips. A length of tape that could hold half an hour’s worth of sound would hold considerably less than a minute of video, after allowing for the amount wasted getting the motor up to the ridiculously high speed. At that rate a reel of quarterinch tape would have to be more than two feet across to hold fifteen minutes of video.

Camras decided to bring the mountain to Muhammad. Instead of pulling tape at lightning speed past a fixed recording head, he decided to move the recording head past the tape. Camras mounted three heads on the face of a rotating drum and attached them to a Hoover vacuum-cleaner motor that turned at 20,000 revolutions per minute (rpm). This allowed him to use tape two inches wide, which reduced the required speed by a factor of ten. He knew he was onto something, but other projects drew him away, and he put the rotating-drum idea aside.

Like Camras, Jack Mullin realized the potential of magnetic audiotape for video recording, though it did not occur to him to use a moving head. In June 1948 he and Wayne Johnson, a BCE radio technician and engineer, started experimenting on a modified Ampex Model 200 sound recorder. They proved the feasibility of pulling quarter-inch tape past a fixed head at high speed, and on November 14,1950, Mullin applied for a patent for “video recording methods.”

In June 1951 Crosby rewarded Mullin and Johnson with a brand-new laboratory at BCE’s headquarters in Hollywood. Sarnoff’s challenge three months later spurred Mullin and Johnson on: The General’s speech, Mullin later recalled, “made us enthusiastic and encouraged us to get busy and work as fast as possible.”

They may have worked too fast. Frank Healey, the prototypical publicity man who ran BCE’s new electronics division, wanted to show RCA and the world that his boss had the upper video hand. The only problem was that Mullin and Johnson weren’t ready yet. They were in the midst of developing a multiplexing technique that would break the signal into twelve tracks: ten for video, one for audio, and one for the synchronization of horizontal and vertical.

On November 11,1951, a month and a half after Sarnoff’s speech, Healey invited the press to BCE’s laboratory for a demonstration. Mullin and Johnson went back to the modified Model 200, using standard quarter-inch audiotape running at 360 ips to record a single track. The tape transport was supplemented with racks of electronics filled with vacuum tubes, all of which yielded a mere forty lines of resolution, one-eighth of the prevailing broadcast standard.

“We had ‘recorded,’ if it could be called that, some TV pictures of airplanes landing and taking off,” Mullin recalls. “When we gave the demonstration, Frank would stand by the monitor and say, ‘Now watch this plane come in for a landing’ or ‘There goes a guy on takeoff.’ It is doubtful the viewer would have known what he was seeing without this running commentary.”

On the basis of this “demonstration,” Healey was bolder than Sarnoff and predicted that BCE would have commercial models in general use within a year. Regardless of Healey’s hucksterism and the poor quality, it was the first public demonstration of television recorded on magnetic tape. Healey had achieved his publicity objective, oneupping Sarnoff and RCA.

RCA executives weren’t exactly sitting on their oscilloscopes, however. Harry F. Olson, chief of RCA’s video recording project, had already assembled a team in Princeton, at RCA’s Acoustical and Electromechanical Research and Systems Research Division. Its goal was to build what Sarnoff dubbed a “Hear-See” machine, which could record both color and black-and-white. Taking a cue from Mullin, the RCA team built four enormous electronic closets, each more than seven feet tall. Using reels of halfinch tape a foot and a half in diameter moving at 360 ips past a fixed head, they could produce four minutes of single-channel black-and-white video. It was a long way from the commercial product Sarnoff had predicted.

Meanwhile, a third company was entering the field. Ampex engineers visited Camras at the Armour Foundation in early 1951 and saw a casual demonstration of his rotating-head video recorder. They recognized its value.

Camras’s rotating head could give Ampex a technological jump on RCA and BCE, and the low-key company could easily keep away from the public spotlight that both its competitors sought out. In October 1951, shortly after Sarnoff’s speech, Ampex’s founder and president, Alexander M. Poniatoff, allocated a modest $14,500 for initial development and started looking for a project leader naive enough not to know the impossibility of the job ahead.

The leader came on the scene by chance. An Ampex employee living in San Mateo had a neighbor who worked in the transmitter house at KQW radio in San Jose (now KCBS in San Francisco). The neighbor’s name was Charles Pauson Ginsburg, and he was dying to get into something related to television. At the employee’s suggestion Poniatoff gave Ginsburg a call, and he liked what he found.

Ginsburg, born on July 27, 1920, had started his electrical-engineering life like most boys of his day: building crystal radio sets and nearly electrocuting himself. He attended several different colleges as a young man, with several different majors, but renewed his interest in electrical engineering after taking a part-time job installing private telephone exchanges. He finally graduated from San Jose State in 1948, with a major in mathematics and engineering. After several years on the night shift at KQW, Ginsburg was offered the position at Ampex, and he began work in January 1952 in an office right next to Poniatoff’s.

Poniatoff was attracted to Ginsburg as much for his enthusiasm as for his technical knowledge. Ginsburg was more open and happy-go-lucky than most of his engineering brethren. “When you talked to him, you knew he was interested,” one colleague remembered. “He was tenacious but easy to get along with. He was able to take suggestions.” Everyone loved to tell him jokes. No matter how bad they were, Ginsburg would start to giggle, then burst into hysterical laughter. His good nature may have stemmed from the fact that he had survived diabetes; he was one of the world’s earliest insulin takers and felt lucky to be alive.

In early April 1952 a precocious nineteen-year-old named Ray Dolby stopped Ginsburg in the hallway and interrogated him about the supposedly secret video project. Dolby had been working part-time for Poniatoff for about three years. In the spring of 1949 Poniatoff had needed a film projectionist and called the audiovisual club at Sequoia Union High School, in Redwood City. The club’s faculty adviser suggested Dolby, and the sixteen-year-old prodigy and the sixty-year-old patrician quickly hit it off.

Whenever Dolby’s school schedule and Ampex’s finances permitted, he worked in the company’s engineering department. During his senior year, in 1951, Dolby acquired national-security clearance for his work on the construction and testing of a multitrack FM recorder for the Naval Ordnance Laboratory. He earned his first patent that summer by perfecting an electronic synchronization technique for Ampex’s audio recorders.

Just as Dolby got on famously with Poniatoff, he also got on with Ginsburg, and the two became fast friends. They started working together on a variety of projects, including what they called the TVR (television recorder). By August 1952 Dolby was ready to drop out of San Jose State and join Ginsburg and the TVR project full-time. He examined the last machine Ginsburg had devised and was not impressed, so he decided to start from scratch. Scavenging the laboratory for parts, he assembled a Camras-style three-headed drum on a 3,600-rpm motor. Using electronics from an Ampex instrument recorder and two-inch tape, he managed to crudely but successfully reproduce some test signals.

The first problem, however, was that the picture wouldn’t stand still. Dolby suggested using two pairs of synchronized heads instead of three single heads, but the so-called Quad assembly sounded like a buzz saw, tore up tape, and threw oxide particles all over the lab. An Ampex machinist, Shelby Henderson, milled the first “female guide” —twin rotating needlelike posts that kept the tape exactly located—to solve the tracking problem. Ginsburg and Dolby were ready for their first show-and-tell.

On November 19, 1952, they played for Poniatoff and a few other executives a fuzzy, indistinct black-and-white video of a cowboy show. When the silent short ended, Poniatoff exclaimed, “Wonderful! Is that the horse or the cowboy?”

The biggest of the many technical problems was playback. Ginsburg and Dolby could record better than they could recover what they had recorded. After some consideration Dolby suggested using a pulse modulation scheme that would widen the range of the signals at playback.

A couple of weeks after the cowboy test, Ginsburg and Dolby taped a Krazy Kat cartoon in which Krazy pulled up to a roadside stand with a sign that read LEMONADE 5¢. At playback, using pulse modulation, the sign was legible. The team had leaped light-years in just a fort-night. The playback was still plagued, however, by what Ginsburg called “Venetian blinds,” periodic horizontal streaks caused by the crossover from one rotating head to the next.

Dolby was lying in bed at his rooming house one Sunday morning in December thinking about that problem when suddenly it occurred to him that “the basic conception and geometry were wrong.” He sketched out a new four-head scheme, then drove the fifteen miles to Ginsburg’s house. The two tried to pick apart the idea but could find no flaws. Less than a month later it tested successfully. By March 1953 the new machine, with its head assembly spinning at 14,400 rpm, could record twice the range of frequencies previously achieved.

The same spring, with his student deferment gone, Dolby was drafted. He left Ginsburg his notes and went off to St. Louis, assigned to teach electronics in an Army school. In June he received a letter from Ginsburg: Ampex had decided to suspend development of the renamed “video tape recorder” (VTR) to work on a stereophonic sound system for wide-screen movies, to be called Todd A-O, for the producer Mike Todd.

While the Ampex and RCA teams were still experimenting, Mullin and Johnson at BCE progressed far beyond their first, crude demonstrations in 1951. In August 1952 they showed off their twelve-track multiplexing system, which moved at 120 ips, at two technical conventions. On October 3, in a demonstration for the project’s five-man staff, Mullin and Johnson played back a black-and-white recording in which, according to Mullin’s notes, “obscure sign lettering was readable and the identity of the personalities in long shots was possible.”

Many problems remained, including flicker, lateral jiggle, and ghosts. Still, the system was good enough to merit another press conference. On Tuesday, December 30, the team showed reporters a jittery recording of the previous Sunday night’s Jack Benny program. According to The New York Times , “those who a little more than a year ago saw the company’s initial attempt to tape-record television off the air expressed amazement over the quality of the pictures obtainable.” Healey, the BCE publicist, promised to demonstrate a videotape “equal in quality to a live telecast picture” by May 1953, and again predicted the commercial production of recording machines within a year.

Despite the lack of actual working VTRs, there was a lot of industry talk about the future of videotaping. In a speech on March 25, 1953, Sarnoff predicted that videotape would make the use of film obsolete for television. A month later Mullin promised commercial television tape from BCE by 1954. He reported that BCE’s group had eliminated flicker and lateral jiggle, reduced the screenlike pattern, and made encouraging progress on the reduction of streaking and ghosts. Two days later Sarnoff predicted a working system within two years.

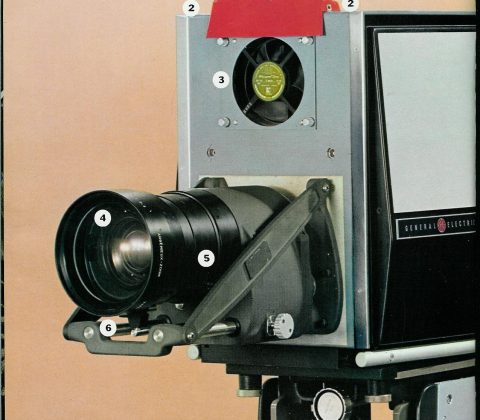

The publicity Sarnoff and BCE were generating sparked video research all over the world. In the United States, DuMont, General Electric, Alan Shoup Labs in Chicago, Bell Television, and the television division of the Federal Communications Commission all went to work on some sort of fixed-head system. In 1952 the British Broadcasting Company embarked on a multiplex VTR project dubbed VERA, for Vision Electronic Recording Apparatus. In July 1953 Eduard Sch’fcller of Hamburg, Germany, applied for a patent on single- and dual-head helical-scan VTRs there. All these efforts eventually faded away.

Ampex’s rotary-head developments were still hush-hush. Although Mullin continued to work with Ampex as a consultant on some audio projects, Ginsburg would play dumb whenever Mullin asked about his video experiments. However, RCA was kept apprised of what BCE was up to. Healey, always eager to blow Crosby’s horn, invited Sarnoff and his staff out to Los Angeles for a demonstration in mid-1953. “They all drove up in three black limos, one guy in each car,” Mullin recalled. Sarnoff sat impassively through the demo, which Mullin later described as “looking like a good half-tone.” Afterward the General was quiet but courteous, said “Thank you,” and left without comment.

Sarnoff must have been burned by Mullin’s relative success. Here was a small group of newcomers running rings around his enormous research complex. But to RCA’s engineers the VTR research was simply a job. Mullin, Johnson, Ginsburg, and Dolby were passionate visionaries as well as engineers.

A differing technical approach was also partly to blame for RCA’s apparent lag. To allow for color recording, Sarnoff’s team was still pursuing the single-channel method, which Mullin had abandoned. “We didn’t have any choice,” an RCA team member explained. “We had the order from God himself that the system we put on the air would have to precisely satisfy the NTSC [National Television Systems Committee, an FCC subgroup] standards for color. We could see no way that one of these other systems ever had a chance of meeting those stringent NTSC standards”—since RCA and Sarnoff had been the prime contributors to writing them, and they naturally favored RCA technology. In the long run Sarnoff was right, but color broadcasting would not become commonplace until the late 1950s. In the short run, with black-and-white still dominant, his decision subjected RCA to much criticism and embarrassment.

RCA’s videotape recording system, called Simplex, had its first public demonstration on December 1 and 2, 1953, at the Sarnoff labs in Princeton. Actually two systems were demonstrated, one for black-and-white and another for color, using recordings of several scenes starring the actress Margaret Hayes. The color system used half-inch tape to record five tracks—one each for red, blue, green, synchronization, and audio. The black-and-white system used quarter-inch tape with two tracks, one for picture and one for sound. Both systems ran at 360 ips. It took more than a mile of color tape to hold a four-minute, 240-line non-NTSC recording, which needed about fifteen seconds to get up to speed.

The press, perhaps cowed by Sarnoff, was respectfully impressed. A trade paper called TV Digest said, “The black & white was better than most kines and as good as some film.” But the General knew better. There were rumors that he had moved the front seats ten rows back to hide the poor picture quality.

Healey was miffed that he and Mullin hadn’t been invited to RCA’s December demos, and he called RCA to request reciprocation. Healey, Mullin, and Johnson traveled to Princeton in June 1954 to see the RCA system. “It was darn good,” Mullin recalled. “It made us realize that we were on the wrong track.” Mullin and Johnson’s system was much more complicated than RCA’s, and while the picture quality was comparable, it seemed to offer less room for improvement. The two went back to Hollywood and abandoned multiplexing for the five-track RCA color method. But they found switching to someone else’s method discouraging. “We didn’t have the enthusiasm,” Mullin admitted. “We had lost our sense of urgency.”

Ironically, Sarnoff had thought RCA was on the wrong track after seeing the Crosby test the previous summer. In January 1954 RCA’s Advanced Development Laboratory in Camden, New Jersey, started a parallel effort to develop a fifteen-track multiplex color machine, but they ran into the same technical problems that had caused Mullin and Johnson to abandon the system. Eventually Harry Olson’s Simplex team would be reduced to working on a cumbersome black-and-white home machine, which was unveiled rather anticlimactically to a disappointed Sarnoff for his fiftieth anniversary in September 1956. Essentially, in 1953 and 1954 RCA and BCE had traded dead ends.

Back in Redwood City, Ginsburg had kept up a lively correspondence with Private Dolby. Ginsburg couldn’t stand his superior on the Todd A-O project and wanted out. Along with Charlie Anderson, who had joined Ampex in the spring of 1954, he continued to tinker secretly with the VTR.

It was a difficult time for Ginsburg, who was officially forbidden to work in video but kept reading about RCA’s and Mullin’s advances. In August 1954 Ginsburg showed a management committee a revamped Quad machine, which incorporated improvements that he and Anderson had surreptitiously made. The executives were sold, and they restarted the VTR project as of September 1.

Once again Ginsburg assembled a VTR team. First of all it included Anderson and Shelby Henderson, the machinist. From the Todd A-O team Ginsburg recruited Fred Pfost, a young expert on recording heads. In October these four and Dolby were joined by the assembly designer Alex Maxey, a twenty-eight-year-old high school dropout and mechanical prodigy who had heard about the project and wangled an interview with Ginsburg.

Dolby returned from the Army in January 1955 to discover two major developments. The first was a new scanning technique. Maxey had turned the angle of the head drum ninety degrees to produce a system called transverse scanning, in which the video signal was written in zigzag lines nearly perpendicular to the direction of the tape. This replaced arcuate scanning, in which the signal was written in lengthwise arcs. The tape speed had also been reduced from 30 to 17½ ips.

The second new development was the creation of a workable frequency modulation (FM) system to replace the previous AM and pulse modulation. Dolby and every other engineer working on magnetic recording had thought that an FM signal would take up too much space on the tape, but Anderson had managed, in essence, to shrink the FM wave.

With that solved, it became a matter of tinkering and time. On January 13, 1955, the team recorded and played back the widest video signal yet. In February new problems cropped up, but they were mechanical, not electronic. Pfost again reinvented the video recording heads, and Maxey fashioned new designs for the tape guide, transport, and rotary drum. Further experimentation and debugging followed, including the addition of an audio track.

On March 2 the Mark I Quad machine was demonstrated for Ampex’s board of directors. The recording consisted of a just-broadcast news report by Eric Sevareid about a ship in distress. As the playback began, Pfost, sotto voce, told Ginsburg to turn up the volume. “With the sound turned up high, the flying spray, the roaring storm, and Sevareid’s booming voice, the board didn’t seem to notice the noise in the picture,” Pfost noted. The picture might not be up to broadcast standards yet, but the team felt the major problems had been solved. They decided to shoot for an unveiling in April 1956 at the National Association of Radio and Television Broadcasters (NARTB) convention in Chicago.

One of the most vexing and persistent remaining challenges was head wear. The material being used in recording heads would last barely ten hours under the strain of video recording. Pfost solved the problem with an aluminum-iron alloy called alfenol, made by the Hamilton Watch Company, which yielded a head that could last thousands of hours. On July 7, with the alfenol head in place, Dolby noted that “overall picture quality was judged the best yet seen.”

By this time Dolby was spending fifteen hours a week at Stanford University, having finally resumed his aborted college career, and three days a week at Ampex. This part-time status created a logistical problem: what title to give to an engineer who had no degree but held or co-held several of the company’s most important patents. Ginsburg arranged for Dolby to be called a consultant. (In June 1957, when Dolby earned his degree, he was promoted to senior engineer.)

Not all the team’s nontechnical problems were as easy to solve. Inevitably there were personality clashes. “We were a bunch of normal people,” noted Anderson. “There were people on the team whom I liked and grew close to; there were others I respected but did not draw close to.” The egos of Dolby, the boy genius, and Anderson, an older and more established engineer, often collided. Pfost, who felt he wasn’t getting the credit he deserved, fought constantly over technical details with the normally jocular Maxey.

Ginsburg, more administrator and mathematician than engineer, mediated technical disputes and refereed the constant bickering. He was the one man everyone respected and liked, the glue that held the factions together. “Charlie was a great leader because he left us alone,” remembered Pfost. “It was a family situation, and Charlie was the father.”

Through 1955, as Ampex went quietly on its way, RCA and BCE engaged in technical brinkmanship with dueling dog-and-pony shows for the press that merely illustrated how far they still had to go. At the dedication of a new 3M research facility in St. Paul, Minnesota, in May, RCA made its first transcontinental broadcast from a color videotape. The imperfect recording contained remarks from Sarnoff, a brief explanation of the system by Olson, and clips of entertainers. Not to be outdone, Mullin demonstrated BCE’s color system in November. According to Broadcast magazine, the recordings “did not match the present live product seen on the color set screen.” Olson and Mullin began to realize that their systems were as good as they were going to get, which wasn’t very. Highspeed, fixed-head video recording simply wasn’t practical.

Meanwhile, word of Ampex’s work started to leak out. Late in 1955 the company tried to downplay it, saying that a practical device was three years away. In fact, three months was more like it. In early February 1956 the team demonstrated its transverse scanning, FM-carrier prototype for thirty Ampex employees, most of whom were seeing video recording for the first time. As soon as the short black-and-white recording ended, the group rose en masse and started applauding and shouting. According to Ginsburg, “the two engineers who had done more fighting between themselves [Pfost and Maxey] shook hands and slapped each other on the back with tears streaming down their faces.”

Several visitors were also shown the system, including William Lodge, CBS’s engineering vice president, and Mullin, who watched with a combination of shock, envy, and disappointment: “I said, ‘It’s all over for us.’ It was a beautiful picture, better than ours.”

The president of Ampex, George Long, told stockholders in a letter that “Ampex has constructed a laboratory version of what is believed to be a practical system for the recording and reproduction of TV pictures on magnetic tape” but hastened to add that “the conversion of this laboratory prototype into a commercially acceptable unit will still require a considerable amount of additional time and effort.” Privately, however, Ampex firmed up plans with Lodge to launch the machine at the CBS affiliates’ meeting at the NARTB convention, less than two months away.

Long might not have believed it when he wrote it, but he was right: The Quad still needed a great deal of work. For the next six weeks Ginsburg’s expanded group virtually lived in the laboratory. “I may have slept in the lab thirty or forty times,” Pfost recalled. Ginsburg even discarded his usual business suit for a work shirt and jeans to pitch in on long nights and weekends. Pfost put in an average of a hundred hours a week experimenting and reconstructing heads. “There were many heroes during this period, but leading them all was Pfost,” Ginsburg later said.

It was decided that two simultaneous official announcements would be made: one at the CBS affiliates’ meeting on Saturday, April 14, and the other at Ampex’s Redwood City offices. The team had been working on a unit called the Mark III, which consisted primarily of a wooden cabinet and two partially filled electronics racks. Mark III would be used for the Redwood City announcement. For the one in Chicago, the team decided to build a more presentable cabinet, designed primarily by Anderson, for what would be an $80,000 machine. The resulting sleek console was dubbed the Mark IV. “It was the most elegant video recorder that Ampex would produce for some time,” Dolby recalled.

The Mark IV was broken down and shipped in pieces to Chicago. By Thursday, April 12, it had been reassembled and was producing its best pictures yet. On Friday the thirteenth, the day before the big Chicago demonstration, a test was run for Lodge and his engineering assistant, who complained about the high noise level. The team tweaked, with limited success, and realized that it needed better tape.

Pfost desperately called 3M’s chief physicist, Wilfred Wetzel. Wetzel and his team spent that Friday night and early Saturday morning coating and testing sample after sample. Wetzel left the laboratory empty-handed early Saturday morning to make a flight to Chicago. Back in the 3M laboratory, technicians had a breakthrough, and at 6:00 A.M. they finished coating two five-minute reels. An engineer frantically drove the package to the airport, dashed onto the tarmac, and persuaded a ground-crew member to signal the pilot, telling him that Dr. Wetzel had to take an important package of medicine with him. The package was hoisted up to the plane’s cockpit at the end of a long pole and passed back to an embarrassed Wetzel.

The new tape solved the last remaining problem. Everything was as ready as it was going to be.

More than two hundred managers of CBS affiliate stations from around the country were jammed into the Normandy Room of the Chicago Hilton on Saturday afternoon, April 14, 1956. Lodge was at the podium to give his annual presentation, and black-and-white television monitors lined the walls to make his speech visible to everyone in the crowded room. When Lodge finished, he said, “Now let’s see what Ampex has for us.” There was a brief delay, and just as the delegates began talking among themselves, the image of Lodge repeating his speech appeared on the monitors. But when the delegates looked at the lectern, Lodge was just standing there. The puzzled delegates once again stared at the monitors. Off to the side some curtains parted. Behind them were three engineers manipulating a gleaming machine the size of a desk.

Although there had been scattered press reports concerning videotape developments, these were usually small articles buried in industry magazines and gave no indication that any system was close to being ready for commercialization. But the station managers slowly realized that they were looking, for the first time, at perfected commercial videotape recording.

Pandemonium engulfed the room. Some in the audience just applauded, some stood on their chairs to get a better look, but most rushed toward the curtained area to examine the new electronic marvel. The exhausted Ginsburg, Anderson, and Pfost were swarmed by backslapping admirers. In four days Ampex took $5 million worth of orders for the new machines.

The video age had dawned.