- Home

- TV History

- Network Studios History

- Cameras

- Archives

- Viewseum

- About / Comments

Skip to content

Director Drew Esocoff

Photo: NBCU Photo Bank

Director Tony Verna

Photo: Courtesy Tony Verna

Director Doug Wilson

Photo: Courtesy Doug Wilson

Director Joe Aceti

Photo: DGA

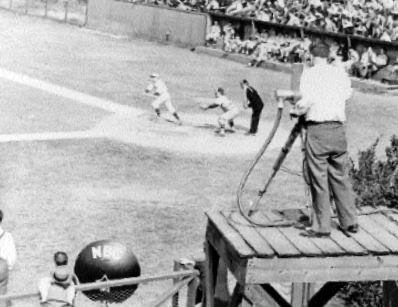

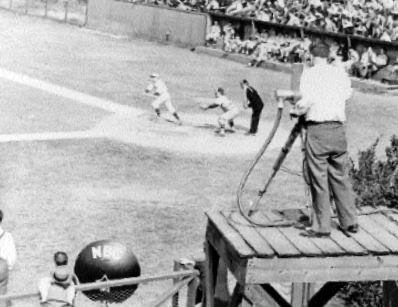

Then and Now: The first game broadcast only used two cameras.

Photo: NBU Photo Bank

Director Ted Nathanson

Photo: Courtesy Edith Nathanson

ABC’s Roone Arledge, with NFL Commissioner Pete Rozelle,

introduced Monday Night Football.

Photo: AP Photo

Director Chet Forte

Photo: Mario Ruiz/Time Life Pictures/Getty Images

Director Bob Fishman

Photo: DGA Archives

Bird’s-Eye View: Directors today command an arsenal of digital tools including

computer-controlled Skycams suspended on a thin wire above the field.

Photo: George Gojkovich/Getty Images

Director Mike Arnold

Photo: John P. Filo/CBS

Source

Posts in Category: Archives

Ever See The Gemini System In Action?

On September 29, 2014

- Archives, TV History

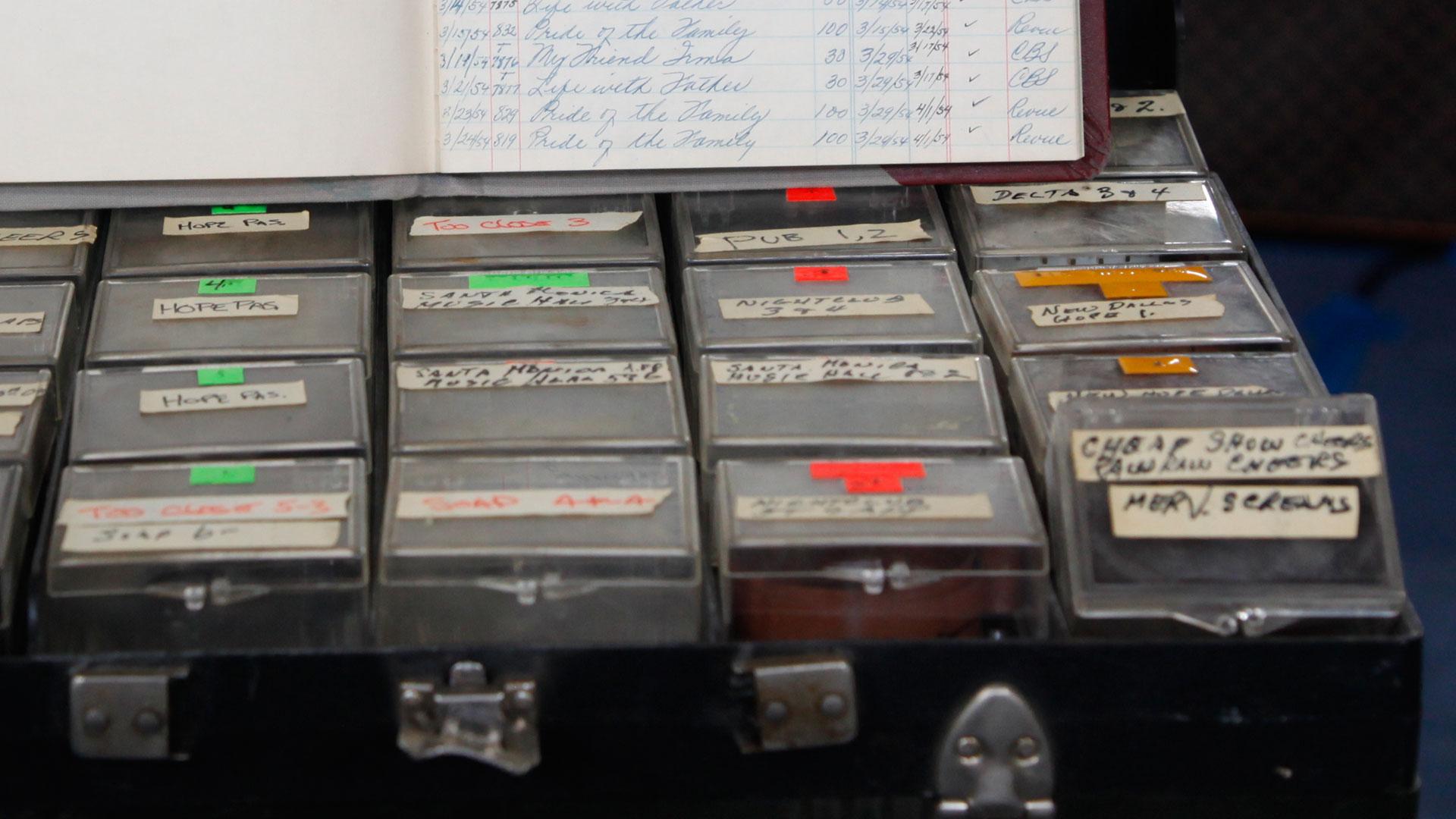

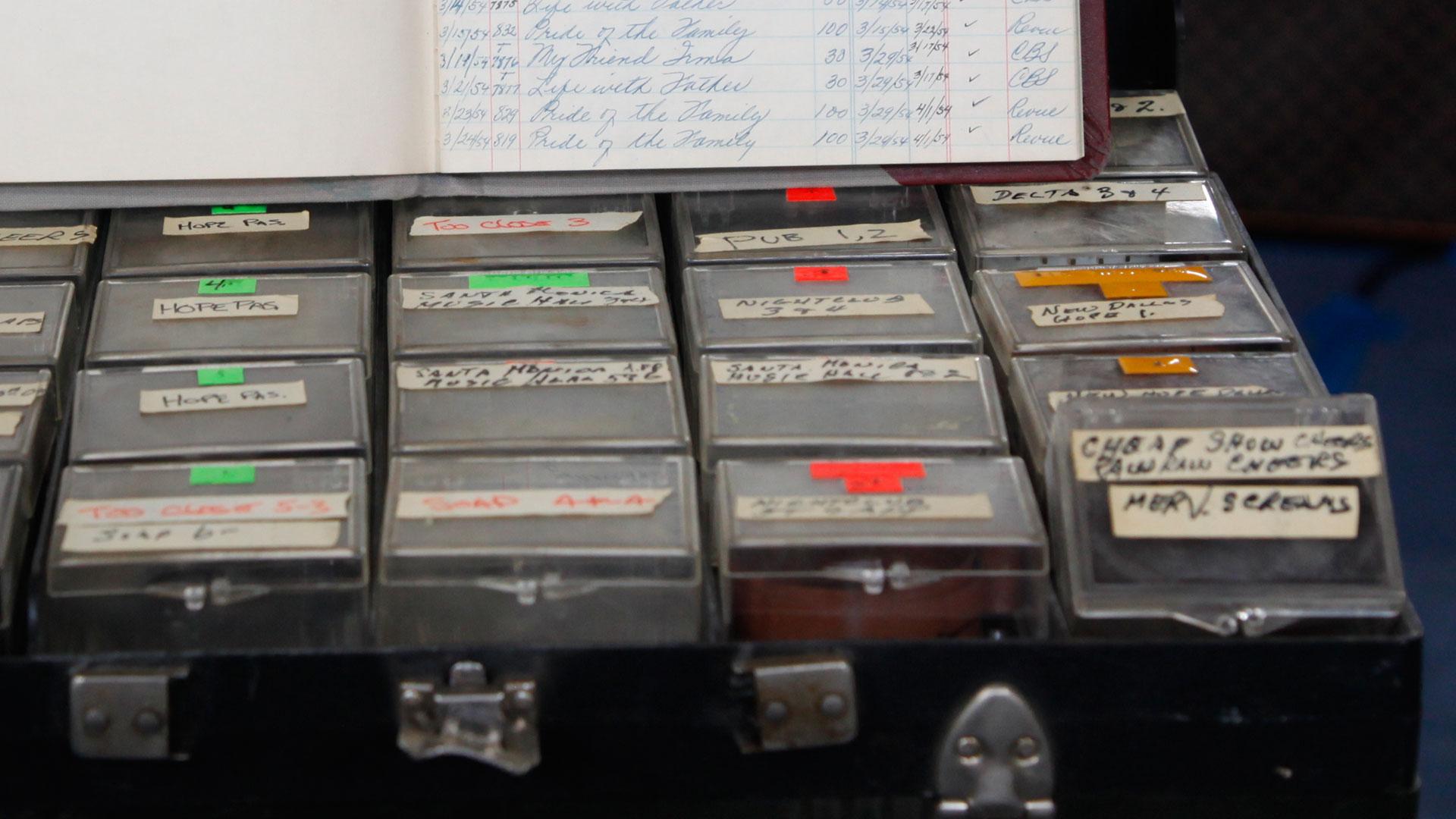

Dumont was first with this video/film hybrid system which they called the Electronicam, and it debuted just before it was used on ‘The Honeymooners’ Classic 39 film episodes in 1954.

This Gemini System from UK optics company Rank (as in Rank, Taylor, Hobson) came out around 1957, and as the Broadcasting Magazine article states, would eliminate the need for Kinescopes. The problem for Rank was that videotape had just debuted too, but there was a need and use for this…especially when it came to commercial production.

Soon after videotape went into service at the networks, national sponsors began asking for their spots on tape. In order to avoid having to shoot the spots twice, once of film cameras and once for television cameras – or to avoid having a kine print, the Gemini came in handy for shooting both at the same time.

Even into the early 60s, many local stations only had one or two of the expensive video tape machines and still had to run spot from film via telecine chains. Thanks to John Schipp for the article. Enjoy and share! -Bobby Ellerbee

The First ‘I Love Lucy’ Episode Filmed…With Schedule

On September 22, 2014

- Archives, TV History

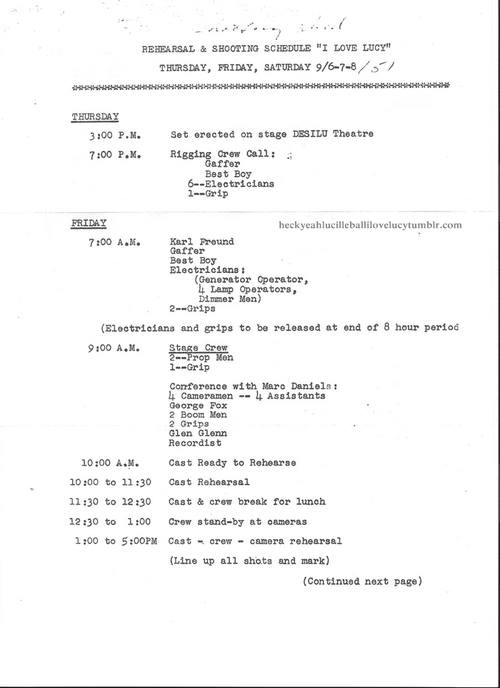

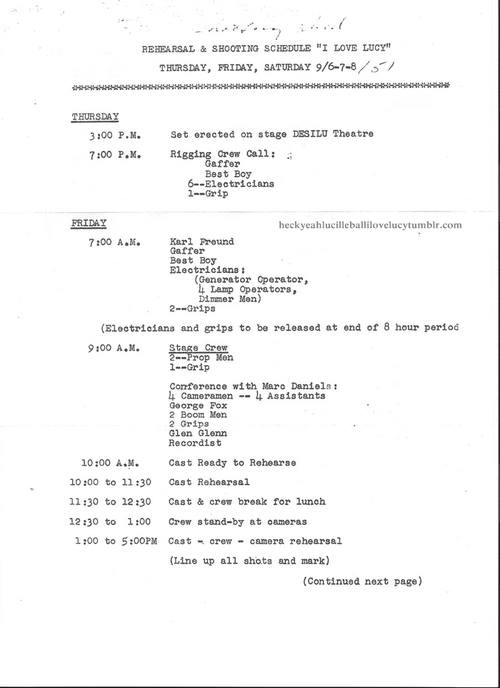

When ‘I Love Lucy’ debuted October 15, 1951, the first episode to air was “The Girls Want To Go To A Nightclub”, but the first episode to be filmed was “Lucy Thinks Ricky Is Trying To Murder Her” which was filmed on September 8, 1951. It aired as the fourth episode on November 5th.

This rare schedule shows the rehearsals and shooting times at The General Services Studios location, which is where the show was done for the first three seasons. Enjoy and share! -Bobby Ellerbee

Directing Football…1939 Till Now! GREAT DGA ARTICLE!

On September 21, 2014

- Archives, TV History

This is the history of football on television as told by some of the greatest ever producers and directors including Chet Forte, Roone Arledge, Ted Nathanson, Drew Esocoff, Tony Verna, Doug Wilson, Joe Acenti, Bob Fishman and Mike Arnold.

This is a must read article written by David Davis for The Director’s Guild Of America’s “DGA Quarterly” Magazine, and covers the topic from A to Z and then some, with things we never knew about how it was all done including the first instant replays and much more. Enjoy and SHARE! -Bobby Ellerbee

http://www.dga.org/Craft/DGAQ/All-Articles/1103-Fall-2011/Television-Football.aspx

Calling the Plays

From the first primitive broadcast in 1939 to the Super Bowl and Skycams, directors have helped invent football on TV. But even with today’s arsenal of tools, the goal remains the same—capturing the action for viewers at home.

By David Davis

Photo: James D. Smith/AP Photo

There was less than one minute remaining in Super Bowl XLIII in 2009. The Pittsburgh Steelers trailed the Arizona Cardinals by three points, but they were mounting a final, desperate rally. The ball rested on the 6-yard line. Every fan inside Raymond James Stadium in Tampa, Florida, all 70,774 of them, were standing and screaming.

In the parking lot next to the stadium, NBC Sports director Drew Esocoff stared at a bank of television monitors arrayed on a wall inside a gigantic production truck. At his command were 52 cameras positioned throughout the venue, images from which flickered on the screens in front of him. In his earpiece, Esocoff could hear the voices of announcers Al Michaels and John Madden describing the action to the 98.7 million Americans watching on television.

The ball was snapped, and Pittsburgh quarterback Ben Roethlisberger went back to pass. Esocoff peered at the monitor showing the live shot of the game while letting his peripheral vision soak in the images flashing on the surrounding screens. He watched as Roethlisberger set himself and hurled the ball toward wide receiver Santonio Holmes, who stretched for the pass in the back corner of the end zone before being pummeled to the turf.

The play ended so abruptly that it was impossible to tell, in real time, what had happened. The fate of the Super Bowl was in the balance: Had Holmes managed to catch the ball and get both feet down, inbounds, and in the end zone, or not?

Director Drew Esocoff

Photo: NBCU Photo Bank

As Michaels and Madden began to debate the issue, Esocoff and producer Fred Gaudelli replayed over and over the sequence from multiple angles and perspectives: from an overhead camera and from both sides of the end zone; from a high-speed camera on a sideline cart that showed the play in super slow motion; from a handheld camera that gave a “defining shot” of Holmes with his feet in the end zone—barely—and clutching the ball.

Then, in a series of rapid-fire cuts, Esocoff used his other cameras to expand the story line. As the two teams awaited the final verdict, Esocoff followed the referee who was consulting a video monitor on the sideline to study the replays captured by the camera crew, then showed reaction shots from the opposing sidelines. Finally, after the referee ruled that the pass was complete, Esocoff toggled between thrill-of-victory and agony-of-defeat shots.

“The losers are sometimes a better visual than the winners,” Esocoff later explained. “We try to pay attention to both sides of every story because you don’t want to get sucked into the mentality that it’s all about the winners.”

Kickoff: The first professional broadcast was in 1939, but the game

that put the sport on the TV map was the NFL Championship

in 1958, often called the “Greatest Game Ever Played.”

Photos: (top) NBCU Photo Bank, (bottom) Robert Riger/Getty Images

Esocoff and his directing peers at Fox and CBS occupy a unique niche. Their three-hour live broadcasts are among television’s most valuable properties. Every week they entertain tens of millions of viewers during the National Football League’s 16-game regular season schedule, the playoffs, and the Super Bowl. In addition, because the footage produced by their cameras helps determine the outcome of each game, everyone with a stake in the NFL—players, coaches, officials, league executives, team owners, media, fans, and fantasy football players—scrutinizes every frame of their work as if it were the Zapruder Film.

It’s a juggling act that requires, simultaneously, intense preparation, artistry, and the ability to improvise under real-time conditions. “Directing the NFL is all about servicing the viewer,” Esocoff explains. “It’s about the personalization of the players and keeping everything focused on the field as best you can. It’s about the documentation of the game—that’s why people watch.”

Directing professional football has come a long way since its inauspicious debut in October of 1939, when the Brooklyn Dodgers defeated the Philadelphia Eagles. From inside a mobile unit parked outside Ebbets Field, director Burke Crotty had two iconoscope cameras at his disposal—and the camera positioned on the field was immobile. The game was shown only on NBC’s experimental station W2XBS in New York; perhaps 1,000 people viewed the broadcast.

The short-lived DuMont Television Network showed NFL games during the mid-1950s, before CBS took over the NFL’s broadcasting chores in 1956. At the time, baseball was the No. 1 sport in the United States. College football was much more popular than the professional version. The Super Bowl and its Roman numerals did not exist, nor did sideline reporters and halftime shows featuring pop stars and “wardrobe malfunctions.” Instant replay had yet to be invented.

Then came the game that changed everything, what is often called the “Greatest Game Ever Played.” The date was Dec. 28, 1958. The place was Yankee Stadium, where the New York Giants were hosting the Baltimore Colts for the NFL Championship.

NBC used four stationary cameras—five, if you count the fixed camera aimed at an easel with cards that read “First Quarter” and the like. The control booth was set up in the back of a van in a parking lot outside the stadium. The game did not pause for TV commercials, and no microphones were allowed on the field to record the sounds of the players. Viewers saw the action in black and white.

Director Tony Verna

Photo: Courtesy Tony Verna

“By today’s standards, it was a nothing broadcast,” remembers pioneering director Tony Verna, who began directing live sports events in the late 1950s and earned a DGA Lifetime Achievement Award for sports in 1995. “It was quaint.”

At a crucial moment late in the game, the rocking of the stadium knocked out an electrical cable, causing television screens across the nation to blacken. An NBC employee ran onto the field, pretending to be a deranged fan, so as to delay the proceedings and enable the network’s technicians to re-establish their live feed with only one missed play.

Still, an estimated 45 million fans tuned in for the Colts-Giants game. It opened the media’s eyes—as well as the “mad men” selling advertising on Madison Avenue—to the awesome potential of the NFL. “A seismic shift in the American sports landscape had clearly begun,” commented Michael MacCambridge, author of America’s Game: The Epic Story of How Pro Football Captured a Nation.

Charged with capturing pro football’s unique combination of physical mayhem and emotional resonance was a new generation of Guild sports directors, including Verna and CBS colleague Bob Dailey, NBC’s Ted Nathanson and Harry Coyle, and ABC’s Andy Sidaris, Jack Lubell, Bill Bennington, and Malcolm Hemion (brother of noted TV director Dwight Hemion). They faced myriad logistical challenges—besides, that is, filming in subzero temperatures in Green Bay and Chicago during December. Unlike in baseball or basketball, helmets and face masks hide football players’ facial expressions. Multiple cameras are needed just to cover the breadth of the playing surface (which measures 120 yards long by 53 yards wide). Most important, in a sport based on sophisticated and well-choreographed offensive and defensive schemes, directors could not isolate on individual matchups—the game within the game—with their “high” cameras positioned above the field.

Director Doug Wilson

Photo: Courtesy Doug Wilson

“The wider you are [with your cameras], the better you can document what’s happening competitively,” says longtime director Doug Wilson, who started with ABC’s Wide World of Sports in the early 1960s. “But that’s less exciting for the viewer because you lose the sense of speed and intimacy. The challenge for the football director is to have the audience feel intimate with the game and, at the same time, be wide enough to show what’s going on.”

That dilemma was exacerbated by the power of lenses in the early 1960s—or, rather, the lack thereof. “When we first started, I don’t think [the zoom lens] was even 20-to-1,” says Wilson, a DGA Lifetime Achievement in sports honoree in 1993. “You didn’t have the opportunity, with the camera on the coverage side of the field, to pick out the eyeballs of the coach on the other side. Today, that’s just magic in terms of telling the story of the game. We take all that for granted now.”

In those early years, Verna says, NFL teams were reluctant to embrace television. “It was very difficult to do anything innovative,” he says, “because the climate was different. The teams didn’t give [our camera operators] good positions on the field. We didn’t have the freedom to move around. Our cameras were on turrets that were bolted down.”

Director Joe Aceti

Photo: DGA

The directors also had to deal with the downtime between plays, often as long as half a minute. “They used to show both teams’ huddles for the whole 30 seconds,” says the late Joe Aceti, the 2006 DGA Lifetime Achievement in Sports Direction recipient, who directed football for CBS, NBC, and Fox. “That gets dull. It’s called television for a reason. It’s about pictures. You want to see pictures of action.”

In an effort to make the broadcasts more exciting, Verna, an inveterate tinkerer, began experimenting with a supply of newly minted Ampex videotape machines. (Television had moved to videotape from film in the late 1950s.) In December of 1963, just days after the televised coverage of the assassination of President John F. Kennedy, Verna unveiled the feature that would revolutionize football, and sports, on TV: instant replay.

Its inaugural use was anything but smooth. During CBS’ broadcast of the annual Army-Navy football game, Verna “instantly” replayed a touchdown run that had just been scored. As the black-and-white pictures flickered onscreen, announcer Lindsey Nelson screeched: “This is not live! Ladies and gentlemen, Army did not score again!”

Aceti remembers that, during the mid-1960s, “it was hell doing replays during live telecasts because it took so long. The tape was 2 inches wide, and you couldn’t see the picture when the tape was rewinding. You had to find it, queue it up, then back off 10 seconds to allow the tape to lock in [during playback]. You didn’t have time to get a lot of replays on the air, except at halftime.”

Then and Now: The first game broadcast only used two cameras.

Photo: NBU Photo Bank

As the technology improved, directors integrated more isolation shots and replays (oftentimes in slow motion) into their broadcasts. This gave TV viewers unique angles on the action—and announcers more fodder to explain the strategic matchups. “Fans on the couch could see what actually happened during the play: how the receiver got open, how the offensive line blocked,” says Verna.

Watching football on television began to outstrip the experience at the stadium. And, during the 1960s, money cemented the symbiotic relationship between professional football and television. NFL Commissioner Pete Rozelle persuaded CBS to pay $4.65 million for the annual rights to broadcast the league’s games in 1962. Just two years later, CBS agreed to pay $14.1 million per season, with the money equally divided among the league’s teams. Meanwhile, ABC was televising the fledgling American Football League under a five-year, $8.5-million contract that ensured its survival. In 1965, NBC wrested away the AFL package with a five-year deal worth a reported $42.5 million.

“The NFL and television—it’s a marriage,” says Aceti. “Pro football is the biggest moneymaker in all of sports. And, without tele-vision, the NFL wouldn’t be half the moneymaking machine that it is.”

In 1966, after the NFL and the AFL merged, Rozelle matched the two league champions in a winner-take-all playoff. For the TV rights to this new title game, he persuaded NBC and CBS to each pay $1 million. They agreed to simultaneously broadcast the game, using CBS’ feed, on Jan. 15, 1967.

Director Ted Nathanson

Photo: Courtesy Edith Nathanson

Dailey handled CBS’ directing effort, while Nathanson, who received a DGA Lifetime Achievement in Sports Direction award in 1991, helmed for NBC. According to Brought to You in Living Color: 75 Years of Great Moments in Television & Radio From NBC by Marc Robinson, “Nathanson arranged to have as big a TV set as could be found mounted in the mobile production truck. He trained a camera on the screen, occasionally zooming in and beaming that tighter shot over the air. The confused CBS crew apparently couldn’t figure out how NBC managed to get its ‘exclusives.’”

The contest between the Green Bay Packers and the Kansas City Chiefs was played at a neutral site: the Los Angeles Memorial Coliseum. It didn’t come close to selling out, even with tickets priced at $12, $10, and $6. CBS charged $85,000 for a one-minute commercial. (In 2011, Fox sold 30-second advertising spots for Super Bowl XLV for approximately $3 million.)

Thus was born the first edition of what became known as the Super Bowl. The idea did not catch on, Wilson says, until January of 1969, when quarterback Joe Namath and the New York Jets defeated the Baltimore Colts. “That was a major jump forward in the appreciation of the Super Bowl,” he says. “From then on, it passed the World Series as the No.1 sports event for the country.”

ABC’s Roone Arledge, with NFL Commissioner Pete Rozelle,

introduced Monday Night Football.

Photo: AP Photo

Perhaps no figure was responsible for inventing modern sports on television more than Roone Arledge, ABC Sports chief and a Guild member from 1960 until his death in 2002. In a 1966 Sports Illustrated interview, he recalled, “When I got into it in 1960, televising sports amounted to going out on the road, opening three or four cameras and trying not to blow any plays…. We began to use cranes, blimps, and helicopters to provide a better view of the stadium, the campus, and the town. We developed handheld cameras for close-ups…. We asked ourselves: If you were sitting in the stadium, what would you be looking at? So our cameras wandered as your eyes would. Sound had been greatly neglected too. All they used to do was hang a mic out the window to get the roar of the crowd. We developed the rifle-type mic. Now you can hear the thud of a football when it is punted.”

Beginning in 1970, Rozelle and Arledge leveraged the league’s popularity and began airing the NFL in primetime. Arledge positioned Monday Night Football as more than just another game. It was “football as entertainment,” as he put it. “Football at night under the lights, helmets gleaming, uniforms dazzling. Even cheerleaders looked better under the lights.”

Director Chet Forte

Photo: Mario Ruiz/Time Life Pictures/Getty Images

Arledge charged director Chet Forte, a DGA Lifetime Achievement in Sports Direction winner in 2000, with making MNF look different. Forte fought the league to allow better access for his handheld and sideline cameras and employed a two-unit, nine-camera crew at a time when NBC and CBS were using five cameras. Said Forte, in an interview from 1972, “What I wanted to do on Monday Night Football was get away from the conformity of CBS and the dictum they laid down for their directors: a wide shot to a tight shot, a wide to a tight, over and over. I wanted to gain impact with enormous close-ups. I wanted to see all the action bigger…. More meaning by going tighter. It’s a little more strain on the cameramen, but they never complain.”

Forte developed his own style and was more concise and exact in the way he followed the action. And, of course, on Monday Night Football he had the advantage of having a broadcast booth unlike any before with the big personalities of announcers Frank Gifford, Howard Cosell, and Don Meredith.

“Roone [Arledge] made Monday Night Football a happening,” Wilson says. “He brought celebrities into the booth and pageantry to the games because he knew that would expand the audience beyond hard-core fans.”

The debut of Monday Night Football marked the moment when the NFL crossed over to the mainstream. And, with technological improvements during the 1970s and 1980s, football on TV turned into a director’s medium. The first generation of directors didn’t have the equipment to really capture the game, but with the advent of better cameras and lenses, the development of the Steadicam, and more experienced engineering crews, football broadcasts continued to improve. Eventually, even the NFL, which was initially resistant to granting access to camera crews, let the directors set up where they wanted to.

Sandy Grossman became CBS’ lead director, as Nathanson continued his successful run on NBC. Meanwhile, as the dominance of the Big Three networks faded, the NFL expanded to cable with the emergence of all-sports powerhouse ESPN in the 1980s.

Today, NFL games are seen on CBS, NBC, Fox, and ESPN, which took over the Monday Night Football franchise from ABC. (Disney owns both ABC and ESPN.) Satellite provider DirecTV is part of the mix, and the league owns and operates Culver City, Calif.-based NFL Network, which airs a slate of games on Thursday nights. All of which has meant more work for, and competition among, today’s directors, including Richard Russo and Artie Kempner at Fox, Bob Fishman and Mike Arnold at CBS, and Esocoff at NBC.

Director Bob Fishman

Photo: DGA Archives

These directors still rely on their “high cameras,” positioned above the sidelines, to follow the action on each play. But football on TV in 2011 looks very different from anything Roone Arledge might have imagined. “It’s night and day from before,” CBS’ Fishman says. “When I look back at games from the 1980s and 1990s, it’s like the Dark Ages.”

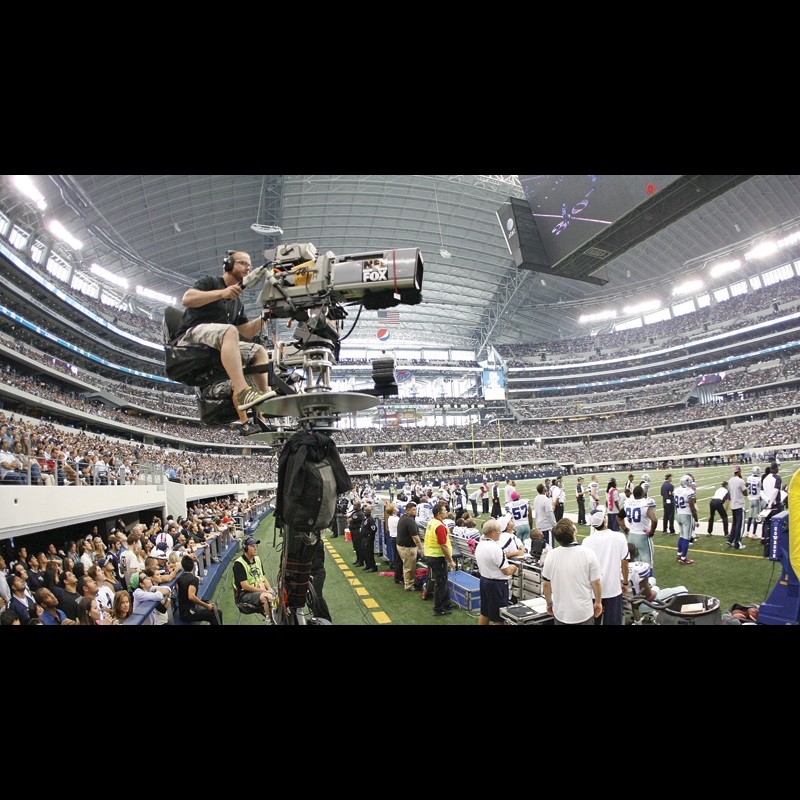

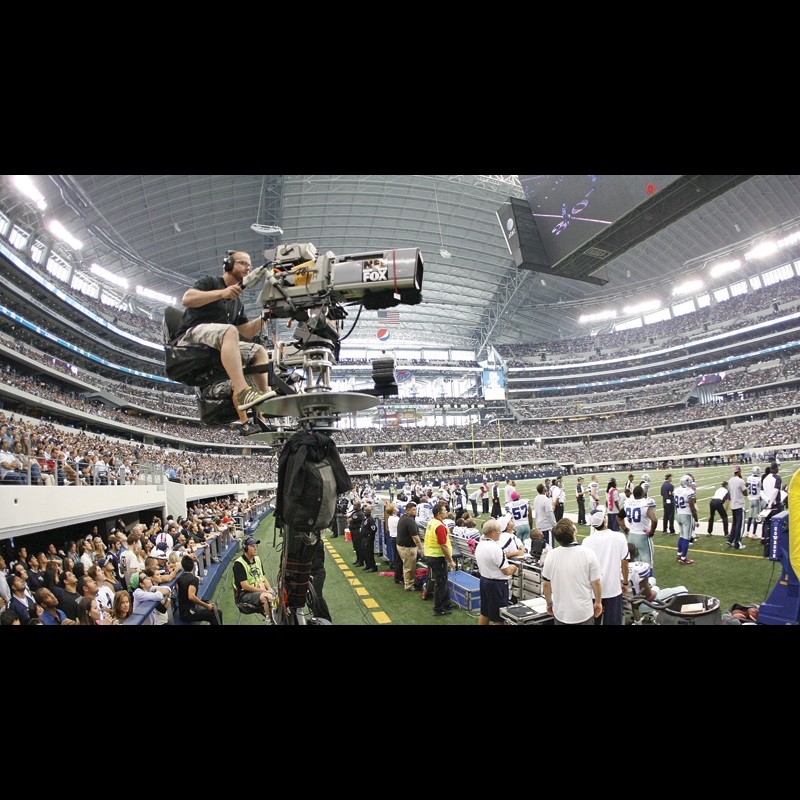

Fishman and his contemporaries now command an arsenal of digital tools. For instance, on a thin wire suspended above the field are computer-controlled Skycams that require a three-person crew to operate. (The Skycam was invented by Garrett Brown, who also devised the Steadicam.) Directors can opt to freeze and spin the picture 180 degrees to show another perspective. For replays, they can access super slow-motion cameras that shoot up to 1,000 frames per second.

Bird’s-Eye View: Directors today command an arsenal of digital tools including

computer-controlled Skycams suspended on a thin wire above the field.

Photo: George Gojkovich/Getty Images

Perhaps the most significant improvement in equipment, Kempner says, involves the power of the Zoomar lenses. “When I started directing [in the 1980s], if you had a 55:1 lens, man, that was big,” he says. “Now, we’ll have eight different 100:1 lenses. We’re able to present the game to the viewer in a way that they’re going to get closer and understand it better. If you really want to see the game, you have to watch it on television.”

The crystal-clear images that appear on viewers’ 60-inch high-definition sets are complemented by an array of graphics packages, including the ubiquitous bright yellow first-down line. The constant clock and score provide fans with up-to-the-second information, while updates from other games crawl at the bottom of the screen. The Dolby Digital 5.1 audio system captures a soundscape of bone-jarring tackles.

The high-definition format is “an unbelievable asset,” Russo says. “We’re shooting 16:9 now [versus the long-established 4:3 format], so we’re shooting on a wider screen than before. If a camera operator is isolating on a wide receiver, he has to make sure the [defensive] cornerback is in the frame. At the same time, you have to work the tight shots and the emotional shots, whether it’s on the field or on the sidelines, so that you can bring the players’ reactions to the viewer.”

For directors accustomed to pacing their broadcasts to the rhythm of the game, the technological toys present their own challenge. “The broadcasts are more graphics and effects-driven than ever before,” says Fishman. “You’re always in a hurry to go to the next package, to show multiple replays of the same play, to send it back to the studio for an update.”

Russo, who directed the Super Bowl broadcast in 2011, preaches patience. “The audience doesn’t know where you’re about to go, but the audience knows where you’re leaving,” he says. “If you have a great reaction shot—whether it’s dejection or jubilation—be patient with that. Don’t be in a hurry to go somewhere else. All that matters is the moment.”

NBC’s Esocoff agrees, recalling that, after quarterback Brett Favre threw the last pass of his career in 2010, he stayed with the camera that showed Favre dramatically walking off the field alone. “The best thing that you learn is to slow down. Cutting more isn’t always better, and sitting on a shot for a little longer may be better,” he says.

The networks previously tried to juice their football broadcasts by attaching miniature cameras to players’ helmets and to the referee’s cap. GPS was also used briefly. Those failures showed only the limitations of technology over the human element.

Director Mike Arnold

Photo: John P. Filo/CBS

On the horizon is 3-D. “You have to approach it in a different way,” says Arnold, who directed a pre-season game in 3-D last year. “You need different camera positions and have to frame things differently. Extreme close-ups don’t work in 3-D, and you need lower play-by-play positions. If you’re too high, you lose the 3-D aspect.”

Regardless of what technical advances may be ahead, directors preach that old-fashioned preparation trumps digital bells and whistles. Kempner spends the week memo of every player to improve his reaction time in the truck. “When you’re directing live, you have no time to look down at your flip card,” he says. “You’ve got your eyes on the monitors. So, when [announcer] Thom Brennaman says, ‘The tackle was by Gilbert Smith,’ who wears number 92, I can instantly say, ‘[Camera] two, give me 92 blue.’

The director’s most important tool remains his crew. Arnold, who directed Super Bowl XLIV, coordinates every facet of the broadcast with his producer, DGA member Lance Barrow. They spend the week before each game speaking with their associate directors, camera operators and announcers, and the statisticians and graphics experts. They watch hours of game film to learn the offensive and defensive tendencies of the opponents, attend practices of both squads, and interview coaches and key players. They scour team and league websites for updated injury reports and monitor players’ Twitter accounts for any incendiary quotes.

“The producer is like the head coach who formulates the overall game plan,” Arnold says. “The director is like the quarterback. It’s my job to execute the game plan.”

Well before the opening kickoff, Arnold and Barrow coordinate the camera positions inside the stadium. The networks use 8 to14 cameras per game; Sunday night crews employ as many as 20. That number rises during the playoffs, climaxing with more than 50 for the Super Bowl.

“We discuss how we’re going to show the game on TV,” Arnold says, “because we’re trying to put the viewer in the best seat in the house. If one team likes to run the ball, we want to make sure we have cameras isolated in the middle of the line to see how the offensive line is opening up the holes.”

On game day, experienced directors have learned not to shape the broadcast to preconceived notions of how the game will turn out. Inclement weather or an injury can suddenly change the tenor of the action. “You can’t script a live event,” Russo says. “Once they kick off, you have no control. The most important thing is knowing the sport because it’s instinctive. You have to be able to react.”

“It’s a live event, so you only get one shot to get it right,” Arnold says. “I’m not minimizing what a film director does on the set, but if we miss a play, we can’t say, ‘The lighting wasn’t quite right. Can you run it again?’”

Fishman remembers the time his friend Francis Ford Coppola watched him direct from inside the production truck. “Francis said afterward, ‘We have the same job title, but our jobs are completely different,’” Fishman recalls. “He had no idea about the pressure we’re under on every play, how much stuff we’re looking at in real time, with no retakes. Then again, we don’t have to deal with any prima donna actors like Francis does.”

The prima donna factor surfaces only during the Super Bowl, when celebrities flock to the big game to hype their latest project. With producer Gaudelli, Esocoff is already planning NBC’s broadcast of the next annual extravaganza in February. He vows to keep his focus on the field. “We’re going to add cameras and graphics judiciously,” he says. “If you change everything you do just for the Super Bowl, you’re a step behind because what you’re used to looking over there to see is not there anymore. We’re not trying to reinvent the wheel.”

Calling the Plays – Directing Football

From the first primitive broadcast in 1939 to today’s Super Bowl, directors have helped create football on TV.

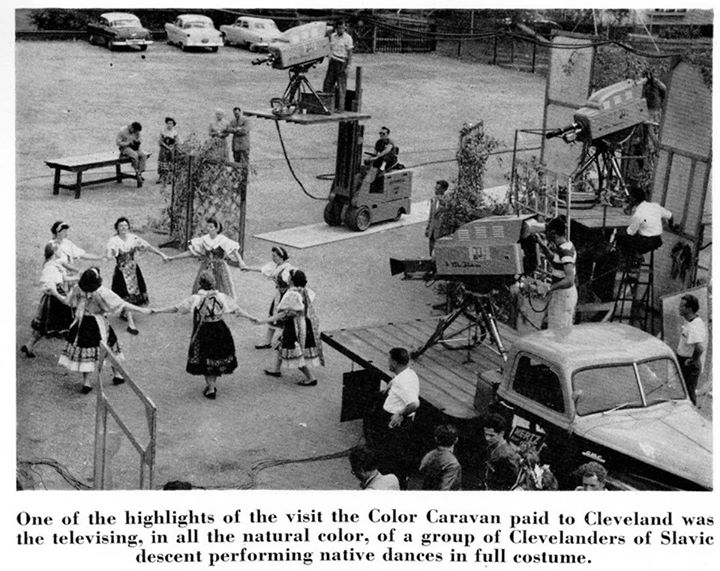

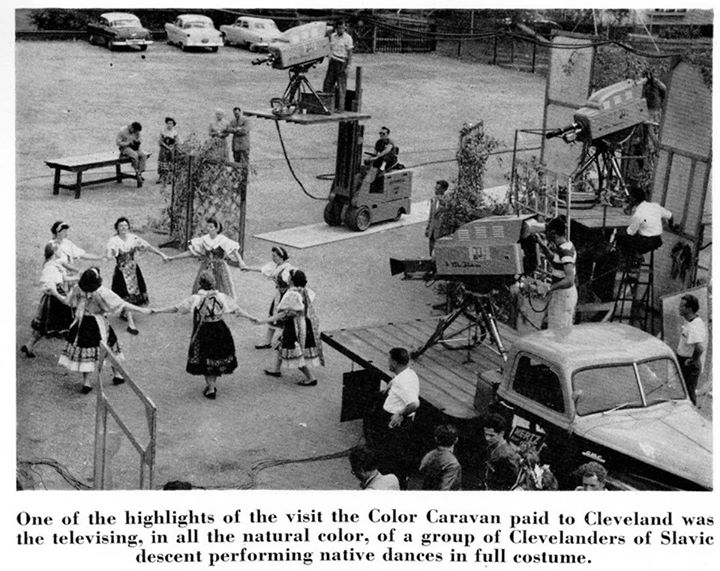

The NBC Color Caravan Story…June 9 – August 11, 1954

On September 18, 2014

- Archives, TV History

RARE! The NBC Color Caravan Story…June 9 – August 11, 1954

Some have heard about this, but for those that haven’t, we finally have the NBC Chimes Magazine article from August of ’54, thanks to our friend Dicky Howett in The UK.

RCA and NBC were proud as peacocks with their new color abilities and took the first two color trucks on the road for a month of live colorcasts that were carried on ‘Today’ and ‘The Home Show’.

On July 9, a crew of eighteen men did the tour’s first color remote from St. Louis as the local stations and major department stores along the way were pre stocked with RCA color monitors and sets for sale and display. The cities they visited also included Milwaukee, Chicago, Columbus, Cleveland, Washington DC, Baltimore and Ft. Meade Maryland. Enjoy and share! -Bobby Ellerbee

Introduction Of The Auricon Pro 1200

On September 13, 2014

- Archives, TV History

Now This Is Interesting! Introduction Of The Auricon Pro 1200

We don’t spend much time on film cameras here, but this is such an interesting piece of film, I thought you would like to see it. Thanks Steve Williams for sharing this.

At first, I thought the “studio finder” was perhaps an electronic video camera used as a video assist, but after seeing this a second time, I think it is just a large ground glass optical viewfinder. I have seen a couple of these in person, but never knew there were small lenses in the center of the turret for the cameraman’s eyepiece. You learn something new every day! Enjoy and share! -Bobby Ellerbee

Source

ABC’s Sacrificial Lambs…GE PC 7 Made Into First ABC Mini Cam

On August 24, 2014

- Archives, TV History

I was digging through some old photos this morning and came across this and it reminded me to set the record straight on ABC’s first homemade mini cameras that we see in use here on ‘Wide World Of Sports’

A while back I had mentioned that they were made from RCA TK30s, but I had forgotten about this picture from ABC veteran cameraman Don ‘Peaches’ Langford. ABC New York had sent a couple of GE PC 7s to LA, but they had no use for them. The man with the big PC7s is Jim Angel and I’m not sure, but it may have been Angel that built the ABC mini cams using parts from these two GE PC7s.

By the way, Don is the one with the bald wig goofing with the mini cam and doing his impersonation of the cameras regular operator who was “follicly challenged”. Enjoy and share! – Bobby Ellerbee

The Most Awesome “Ballet” In All Of Television! SLN Timelapse

Here’s a fantastic 2 minute time lapse look at ‘Saturday Night Live’. This was shot a on April 5 of this year and features Pharrell Williams singing “Happy” and Anna Kendrick as the host. Remember that?

I was there a month later on May 3rd. My seat was on the floor, front row left as you look at this. I can’t even begin to tell you what a joy it was to watch these pros at work! Honest to God, it’s a ballet!

5 pedestal cameras, the Chapman Electra crane and two sound booms all have to move in unison from one end of 8H to the other as the sketches move from stage to stage. All the while, there are 30 or so stagehands striking and setting up scenery all around you. Plus, there are cast members, PAs, Q card and utility men and floor directors in constant motion!

To the crew, the cast and everyone associated with ‘SNL’ I only have 4 words…YOU ROCK! THANK YOU! – Bobby Ellerbee

Videotape Ground Zero…A First Hand Account From Fred Pfost

On August 20, 2014

- Archives, TV History

This is a fantastic, first hand account from Ampex videotape team member Fred Pfost of the entire process of creating the VR-1000… the world’s first commercially viable videotape machine.

This is a rare front row seat to one of television’s biggest ever moments and beautifully told by someone who was there. There are details here you will never see anywhere else, so save this historic treasure and share it with you friends! – Bobby Ellerbee

Here’s A Rare Sight & Great DGA Article…’I Love Lucy’

On June 30, 2014

- Archives, TV History

This is a fascinating article from Ted Elrick in “The Director’s Guild Of America Quarterly” on how the show was done. There is a lot of information there you won’t read anywhere else. The whole article is copied below.

http://www.dga.org/Craft/DGAQ/All-Articles/0307-July-2003/I-Love-Lucy.aspx

In the photo, we see Desi Arnaz with Jess Oppenheimer looking at a control booth under construction at General Services studio just before the show started production. This is probably around August of 1951.

Now this is really more of an audio and intercom center than anything else, because as you remember the show was shot on film, but coordination was still a key factor in the production. All the camera, dolly and boom people wore headphones. I would think there was an assistant director in the booth reminding them of cues and the DOP and director would be on the studio floor. Enjoy and share!

I Love Lucy

Directing the first multi-camera film sitcom before a live audience.

BY TED ELRICK

Desi Arnaz and Lucille Ball in I Love Lucy

On October 15, 1951, television broadcast history was made when the first episode of I Love Lucy aired on CBS. Technically, it was not the first episode of the show. The pilot, directed by Ralph Levy, was recorded as a kinescope, a 16mm filmed recording taken from an extremely bright cathode ray tube, but it was not broadcast until 1990. Kinescopes are fuzzy and often distorted, but were the only means for communities outside of the reach of coaxial cable linked network affiliates, predominately on the East Coast where most television programs originated, to see network programming. Lucy was the first multi-camera sitcom to be filmed before a live studio audience.

Its genesis was really something of a fluke, primarily driven by a cigarette manufacturer’s objection to kinescope films. When I interviewed him in the late 1970s, Desi Arnaz said that CBS and the show’s sponsor, Philip Morris, objected to making I Love Lucy in Los Angeles. The sponsor in particular didn’t want the lucrative New York and East Coast market, accustomed to quality broadcasts, seeing their show the way the rest of the country saw other shows, on kinescopes.

Lucille Ball and Desi Arnaz were adamant that this production stay in Los Angeles, where they had made their home for several years. A compromise to “film” Lucy was reached after the network’s complaints about the increased costs of shooting in that medium were offset by Arnaz and Ball agreeing to take a cut in their weekly salary. In return for this salary concession, CBS agreed that Arnaz and Ball would own the shows after they were broadcast. Both were truly surprised by CBS’ concession. That move alone would eventually make Desilu Productions one of the most powerful independent companies in television.

However, the problem remained of how to film the show. Many cinematographers said it was impossible to film multi-camera before a live audience. Different lighting requirements were needed for master shots, medium shots and close-ups. It just couldn’t be done. But that was not a phrase in Arnaz’ vocabulary.

He called veteran cinematographer Karl Freund, then in his early sixties, who told Arnaz the same, “It can’t be done.” According to Stefan Kanfer’s new book, Ball of Fire, The Tumultuous Life and Comic Art of Lucille Ball, Arnaz replied, “Well, I know that nobody has done it up to now, but I figured that if there was anybody in the world who could do it, it would be Karl Freund.” Needless to say, flattery got Arnaz everywhere, and Freund set to work, eventually accomplishing what couldn’t be done.

Film considerably raised the bar on broadcast quality. Suddenly, people across the country all saw the same image, and they liked it. I Love Lucy was a hit.

Live Audience and Directing

In his book, And the Show Goes On, television pioneer Sheldon Leonard wrote about another of Arnaz’ decisions: “Operating on the well-founded belief that a comedy show needs an audience to give it the authentic response that canned laughter can never duplicate, Desi brought in an audience to watch and react, while he used multiple-camera shooting technique borrowed from live TV.”

Arnaz also “borrowed from live TV” director Marc Daniels who would sit in the director’s chair for the filmed I Love Lucy. Daniels’ contribution to choreographing three-camera technique was considerable and influenced generations of television directors.

James Nicholson, William Asher and William Quine on the backlot at Columbia Pictures.

Daniels would direct all of the first season’s 35 episodes, a season uninterrupted by today’s all-too-common reruns. In the DGA Oral History, The Days of Live edited by Ira Skutch, Daniels said, “I’d had the multiple-camera experience. [Lucy] was similar to live, except that the film cameras were much less flexible than the television cameras. You were stuck with the side cameras being the long lenses for close-ups and the center camera being the master camera, and you couldn’t change a lens as quickly.

“We began I Love Lucy using four cameras because they wanted to do the entire first half of the show without stopping,” Daniels continued. “We had four Fearless dollies, four dolly grips, four camera assistants, two booms, two dolly grips for the booms, and a few cable men. You can imagine what that floor looked like.”

After the first season, Daniels moved on to direct other shows. William Asher, who would later produce 285 episodes, and direct 200 episodes himself of another television classic, Bewitched, came on board, becoming the directing mainstay for many years, and further refined and perfected multi-camera technique.

Trouble on Day One

Asher’s first day on the set though nearly ended his association with the show. They had begun rehearsal and Asher had to walk away for a bit to attend to some technical matters. When he returned, he discovered that Lucille Ball had been giving directions backstage. Asher was astonished.

“I said, ‘Lucy, there’s only one director. I’m it. If you would like to direct, then don’t pay me and send me home,’ ” Asher said. “When I said that, she began to cry and ran off the stage. Everybody disappeared. Desi hadn’t been in the scene. I didn’t know where to go because I had no office. So, I went to the men’s bathroom, sat on the toilet and didn’t know what the hell to do. I realized I’d blown my first day of what was really a pretty good job.

“I sat there for a long time and finally got up and went back to the stage,” he continued. “Desi was there. He was furious. He was cussing me out in Spanish and I didn’t know what he was saying. I settled him down and said, ‘Look, Desi, here’s what happened.’ And he said, ‘Well, you’re absolutely right, Bill. What you should do is go in to Lucy’s dressing room. She’s crying. Go talk to her and settle this thing.’ So that’s what I did. I went in. I said I was sorry I upset her. And she was crying and I started to cry. And after a while we went back to work. But I’ll tell you this. I never had trouble from her after that. She had her opinion, and would offer it, but nothing ever behind my back. Everything was just fine. That’s the way it was for the next five years.”

On the set of I Love Lucy with Lucille Ball and William Asher

Scripts, Rehearsals and Showtime Folks

Asher said they began working on each season of Lucy with between six and seven scripts that were in very good shape. “The scripts were excellent,” Asher recalled. “We had only the producer [and head writer], Jess Oppenheimer, and two other writers who wrote as a team [Madelyn Pugh and Bob Carroll, Jr.]. And that’s all we had. Today you see 9, 10, or more writers.” Oppenheimer, Pugh and Carroll had also been the writing team of Ball’s hit radio comedy My Favorite Husband. In Lucy’s later years Bob Schiller and Bob Weiskopf would write episodes.

Asher said there was very little ad libbing because the material was strong and they’d had time to rehearse. “On Monday morning we would read the material, discuss it and make changes. In the afternoon, I would start rehearsing and continue rehearsing Tuesday and Wednesday when the cameras came in. On Thursday, we’d rehearse again with cameras about half the day. Then we would do a dress rehearsal. Later that day, we’d do the show.”

Rehearsals were vital because they were shooting film. At the time there were no monitors for the director to see the image. The show’s quality depended on his ability to watch the floor and ensure that all cameras and actors hit their marks at the required moments. Precision was crucial, as nobody wanted to halt the performance in front of an audience. They rarely shot pick-ups, Asher said, and when they did it was usually for a guest star who forgot a line. Most shows were filmed in around thirty minutes.

“We had stops for Lucy’s big costume changes, but that was all,” Asher said. “I had a pretty strict rule on that. We didn’t stop for anything. We played it like a Broadway show. If an actor made a mistake or forgot a line or something like that, it was up to the other actor to get him out of it.”

(Top) Lucille Ball performs the famous “Vitameatvegamin” scene (Below) Lucille Ball, William Frawley, Vivian Vance and Desi Arnaz in a scene from I Love Lucy

Asher can recall only one time when the show came to a dead stop. “Lucy always had one moment where she’d get stuck. We’d put that line of dialogue on the back of a lamp or something where we knew she’d be working. Once, right in the middle of a scene she suddenly stopped. And she was the only one in the scene, alone in the living room. I waited and waited. She just was staring at something. Finally, I yelled ‘cut’ and ran down to the set and saw she was staring at the back of a lamp where we’d put her line. She said the line didn’t seem right to her. It turned out that the lamp we were using in that show broke after dress rehearsal, and the crew brought in another lamp that had a line from a previous show from the year before on it. We explained it to the audience and replaced it with the right line and went on. It was the only time we stopped.”

Yet Another Innovation

On Friday, Asher would cut the show with the editor, and on Monday, during lunch following the next show’s read through, he’d watch the prior week’s show with Arnaz who would give his comments.

The editing of I Love Lucy brought another major innovation to television. Arnaz said that when he first sat down to watch the film, he found it very confusing to look at only one camera’s footage on a Moviola. He asked why he couldn’t see the film from all three cameras at the same time. He was told that this was the only way — one camera’s film at a time. Arnaz pushed the issue and asked, “Why can’t you just stick three Moviolas together?” So the production team contacted Moviola’s president, Mark Serrurier, son of Iwan Serrurier who had created Moviola in 1924. A graduate of Caltech who oversaw the design of the dome and structural parts of the 200-inch Palomar Telescope, Serrurier developed a three-headed machine to speed up the editing process on Lucy.

Jay Sandrich, who would establish his own directing legacy on The Mary Tyler Moore Show, Soap and The Cosby Show, began his career as a 2nd AD on I Love Lucy. He moved up to 1st AD when Jack Aldworth moved up to producer. “I was 24 and I knew nothing,” Sandrich said. “I was learning on the number one show in the country. Aldworth was a wonderful mentor who really helped me.”

After thousands of reruns in syndication, it’s sometimes easy to forget just how innovative I Love Lucy was to the history of sitcoms. But it set the stage for further technical innovations, for influential independent producers like Sheldon Leonard, Norman Lear, and Grant Tinker, and for strong directors whose voice and commitment to the idea that “There can be only one director” would continue to perfect the uniquely American art form known as the sitcom.

Confirmation! CBS Buys Marconi Color Cameras…October 31, 1966

On May 28, 2014

- Archives, TV History

It was always my opinion that CBS only kept the Norelco PC60s at Studio 50 (The Ed Sullivan Theater), for eighteen months or so. Now that is confirmed with this article that appeared on my sixteenth birthday in Broadcasting Magazine.

In another Halloween quirk, it was October 31, 1965 when the ‘Ed Sullivan Show’ went color in Studio 50 with the Norelcos. The show had actually been broadcast in color the prior three weeks, but those shows came from Television City while the New York studio was being finished.

As stated in the article, the five Mark VIIs would arrive in the summer and that makes eighteen months. As we’ve learned, Studio 50 had big magnetic field problems caused by the subway generators just behind the backstage wall. In field tests of a prototype Mark VII, that was not much of a problem but it was for the Norelcos. As Paul Harvey would say, “Now we know…the rest of the story”.

June 19, 1946…The debut of the RCA TK30s…

On May 19, 2014

- Archives, TV History

The debut of the RCA TK30 Image Orthicon camera was live in half of the nation and on kinescope for the rest, so this better be good! And it was! This was trial by fire.

RCA worked so fast to get six TK30s to NBC in New York for the Lewis-Conn rematch at Yankee Stadium, the art department didn’t even have time to cut and paste photos of the cameras in their pre fight ads that ran in May of 1946.

In the photos on the right and left, you see the first TK30s ever used anywhere…even on a local NBC NY show. The introduction date was officially set for October of ’46, but the Lewis-Conn rematch was such a big deal that production was moved up to get at least a few in service for the fight. NBC covered the fight on radio and television on the full network. This was television’s first ever coverage of a World Heavyweight Championship bout.

In the RCA ad in the center we see the immediate predecessor to the TK line of Image Orthicon cameras. These are RCA Orthicon cameras…better than Iconoscopes, but still not half the quality of the IO cameras.

Here’s a little history on this Lewis-Conn rematch…one long delayed by WWII. In 1942, Conn beat Tony Zale and had an exhibition with Louis. World War II was at one of its most important moments, however, and both Conn and Louis were called to serve in the Army. Conn went to war and was away from the ring until 1946.

By then, the public was clamoring for a rematch between him and the still world Heavyweight champion Louis. This happened, and on June 19, 1946, Conn returned into the ring, straight into a world Heavyweight championship bout. Before that fight, it was suggested to Louis that Conn might outpoint him because of his hand and foot speed. In a line that would be long-remembered, Louis replied: “He can run, but he can’t hide.” The fight, at Yankee Stadium, was the first televised world Heavyweight championship bout ever, and 146,000 people watched it on TV, also setting a record for the most seen world Heavyweight bout in history. Most people who saw it agreed that both Conn and Louis’ abilities had eroded with their time spent serving in the armed forces, but Louis was able to retain the crown by a knockout in round eight.

Reports on the television coverage were glowing too! These cameras had delivered the clearest, sharpest pictures ever and with four lenses on the turret, were able to offer a never before available range of shots per camera with 24 views of the action.

Television’s First Sportscaster…Bill Stern

On April 20, 2014

- Archives, TV History

In the center is an NBC publicity photo of Bill Stern. Mr. Stern is the man that called the action on the first ever televised sporting event…the second game of a baseball doubleheader between Princeton and Columbia at Columbia’s Baker Field on May 17, 1939 as seen on the left.

On September 30, 1939 he called the first televised football game. It was a college game between the Fordham Rams and the Waynesburg Yellow Jackets played at Triborough Stadium on New York City’s Randall’s Island. Fordham won the game 34–7 and a photo from that game is on the right.

NBC hired Stern in 1937 to host ‘The Colgate Sports Newsreel’ as well as Friday night boxing on radio. Stern was also one of the first televised boxing commentators. Many say that Paul Harvey copied Stern’s style and his stories about the famous and odd, which Harvey called “The Rest Of The Story”. Although Stern made no effort to authenticate his stories, in later years, he did however introduce that segment of his show by saying that they “might be actual, may be mythical, but definitely interesting.”

Thanks to Jodie Peeler for the wonderful and rare color photo… more of those soon!

A Brief History Of Portable Color Cameras

On April 18, 2014

- Archives, TV History

You would think RCA lead the way in this area, but they were more focused on studio color cameras in the late 60s as the TK42/43 project had gone badly and Norelco was eating their lunch. Now, this is not to say that there were not some RCA/NBC experimental color portables in use, but they were not production models…just testers.

That I know of, ABC had the first color portables and this video clip shows the camera on the sidelines of the USC-UCLA game on November 11, 1967. There were two backpack versions…one contained a small video tape recorder and no live capacity, but the one shown here is the “Scrambler” pack which is a control and microwave box. In the photo below is our friend Don ‘Peaches’ Langford with the BC 100 and was one of the first to use this camera.

Just a month earlier, in October of 1967, Norelco announced it’s first color mini camera, the PCP 70, at National Association of Educational Broadcasters convention, but most think it was just a prototype that was not ready for field use. The camera head, with zoom lens weighed in at 23 pounds. The backpack was an additional 22 pounds. The list price was $41,450.

To be fair to RCA, the color portable they introduced August 25, 1968 at the political conventions had been in developed the year before for use on the NASA Moon missions. Here is a link to the story on that camera.

August 25, 1968…NBC Debuts Color Portables In Chicago

Third on the scene with portable color was Ikegami. In 1972, the HL 33 (Handy Looky) debuted. The HL 33 also had a large back pack, but did lead the way in Electronic News Gathering and is generally considered the first ENG camera.

Although bringing up the rear, it was RCA that finally did away with the backpacks, which brought great joy to the camera crews. The RCA TKP 45 (see earlier post for introductory video) debuted in 1974 as a camera only unit which cabled directly to the truck. It was more of a production color camera than and ENG but could handle the task.

Finally in 1976, RCA rolled out what would become the top of the line and most used ENG camera ever, the TK76. In the last part of the TKP 45 video, we see the 1975 engineering model of the TK76. Here is the full story on that 1975 RCA ENG camera that never had a name, as told by our friend Lytle Hoover. Enjoy and share!

http://www.oldradio.com/archives/hardware/TV/tk75.htm

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=_kh8JurXv2c

Ignore the annoying bugs; here’s a quick clip of Ampex’s portable Ampex BC-100 camera in action, at the November 11, 1967 UCLA-USC game–which I had thought …

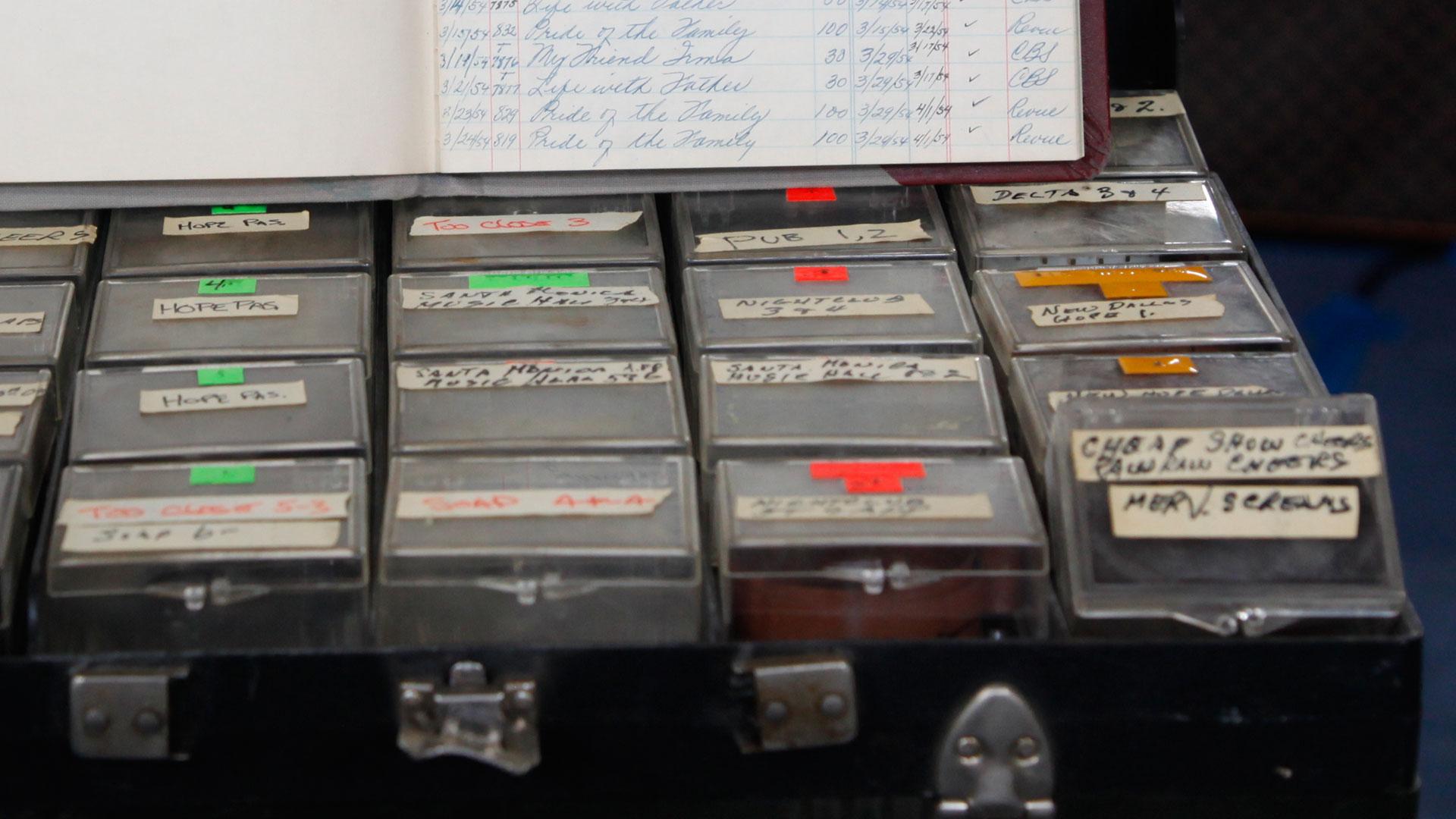

1953 Charlie Douglas’s “Laff Box” Discovered

On April 17, 2014

- Archives, TV History

Laugh Tracks: Ultra Rare Black Box Found!

This is an amazing find! From ‘Antiques Roadshow’ here is the video of the Charlie Douglas ‘Laff Box’, built in 1953, which was discovered among the items sold in a storage locker sale!

Back in the 50s and 60s, Charlie Douglas was ‘The Man’ for laugh tracks in Los Angeles and traveled with his top secret black box to sweeten the tracks on many famous shows.

He would wheel his black box of pre-recorded laughs into the post audio room, plug in to the mixing console, and proceed to treat the soundtrack with everything from chuckles to knee-slapping fits, to applause.

Understandably, Charlie and his son Bobby were very protective of the technology and the library of carefully categorized audience reactions inside that black box. Now remember, this was before cart machines, but when the close up comes, you’ll see the loops rotating and I think this technology was called the Mckinzie tape loop system. Thanks to Mark Sudock for the clip. Enjoy and Share!

April 11, 1956…Ampex Debuts Video Tape At NAB

On April 11, 2014

- Archives, TV History

April 11, 1956 is a day that truly changed television! Here it the story of that day and the hectic months at Ampex that followed this blockbuster announcement.

On April 11, 1956, Ampex engineers Phil Gundy and Charlie Ginsburg introduced one of two existing video recorder prototypes to the National Association of Radio and Television Broadcasters (NARTB) Convention in Chicago, later renamed the National Association of Broadcasters (NAB). The second prototype had its introductory demonstration simultaneously in Redwood City.

What was unforgettable about the 1956 introduction was the event that occurred the day before the opening of the convention in Chicago; the April 10th CBS annual meeting for television personnel, held at the same convention center.

This was to be a “state of the company” presentation by Bill Lodge who was head of television affairs at CBS. The meeting was to be held in a small auditorium that was about 100 feet deep and maybe 70 feet wide. Three television monitors were spaced along each side, so that all in the audience could see and hear Lodge as he spoke at the podium. There was a curtain behind him as he stood at the podium. CBS personnel and affiliates began to stream in and take their seats – maybe 200 in total. Little did they know what Bill Lodge and Ampex had in store for them!

Earlier that morning, Charlie Ginsburg and Charlie Anderson had set up their Ampex videotape recorder behind the curtain so it would not be seen by the audience – at least at first. Fred Pfost arrived a short time later. Together, they checked out the system, and it was working perfectly; they were ready! Pfost started the recording as Lodge made his introductory remarks, continued with his presentation of what CBS had accomplished in the current year, and described his plans for the coming year. He mentioned a rumor that many had heard – that Ampex was working on a videotape recorder – and said that he had visited Ampex and was impressed with their development project, and had given them a small contract to help finance their development efforts.

Then, Bill Lodge opened the session to questions and answers. That was the signal for Fred Pfost to rewind the tape. When Bill received the signal that the tape was ready to play, he concluded his presentation with much applause. That was Fred’s cue to press play: when the audience saw the replay on the same monitors as the original presentation, they went wild with shouting, screaming, and whistling. When the curtains were opened to show the Ampex videotape recorder, some stood on their chairs to get a glimpse of it. These television people realized that what they were seeing for the first time was a recorder that would greatly simplify production of video programs and also be an excellent answer for recording delayed television broadcasts.

What Ampex had just done for the television industry is the same thing it had done for both the radio and audio-recording industries some seven or eight years earlier. This was truly a revolutionary moment for television. Fred Pfost has said that every time he tells the story of this event, it brings tears to his eyes. He still feels it is one of the most exciting moments of his life. When the Convention opened the following day, everyone had heard about the introduction of the Ampex videotape recorder at the CBS meeting, and Phil Gundy announced that 11 presidents of the major television networks from around the world were standing in line to see the recorder – and learn how soon they could purchase it.

In less than a week, he received orders for 45 Model VR-1000 recorders at $45,000 each. Phil also received a contract from CBS for modified prototypes (similar to the one shown at the Convention) with the proviso that the network get them soon as possible. These required custom engineering, and cost considerably more.

With the introductions over, Ampex now had to redesign the prototypes for production, tool them, produce them and ship them all by April, 1957 in order to meet the beginning of daylight saving time that year. John Leslie headed an overlay team that bridged application engineering, product engineering, manufacturing engineering, manufacturing and quality assurance. Ampex shipped the VR-1000 recorders on schedule.

CBS Television City got the first five and NBC Burbank got the next three. The deliveries were made the same month NBC Brooklyn II, Burbank Color City Studio 4 and, the all color, Ziegfeld Theater went into service.

Below the first VR 1000 ready to ship and a bottom, the November 30, 1956 first-ever, nationwide tape-delayed broadcast. CBS replayed ‘Douglas Edwards With The News’ from CBS Television City for the Mountain and Pacific time zones.

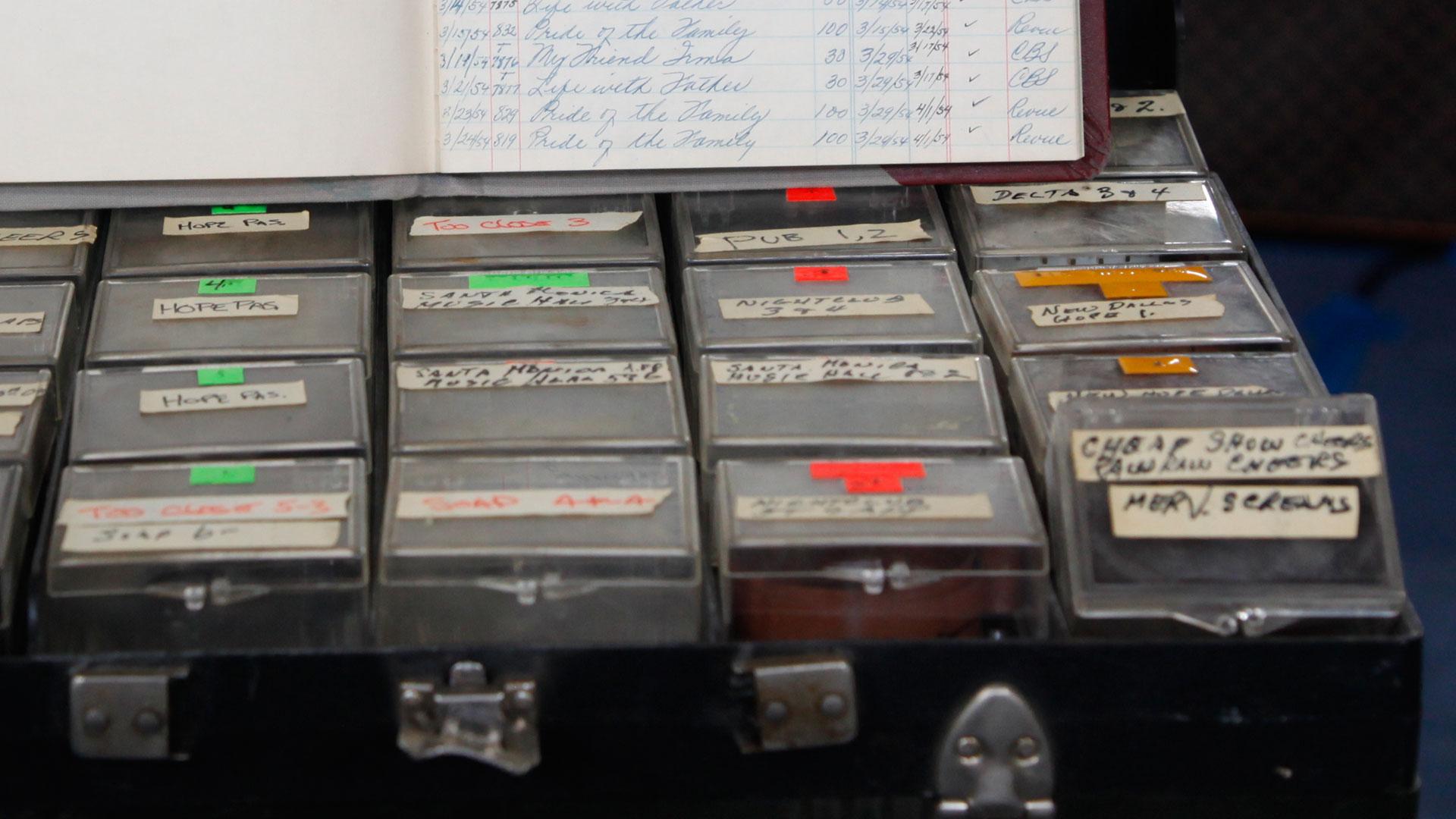

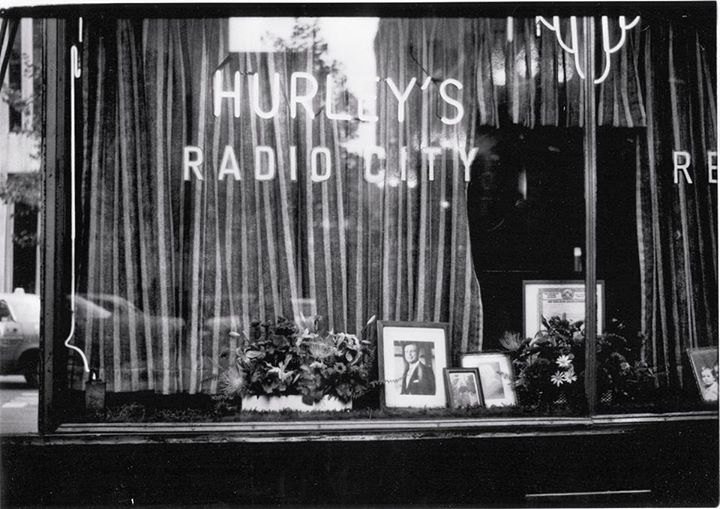

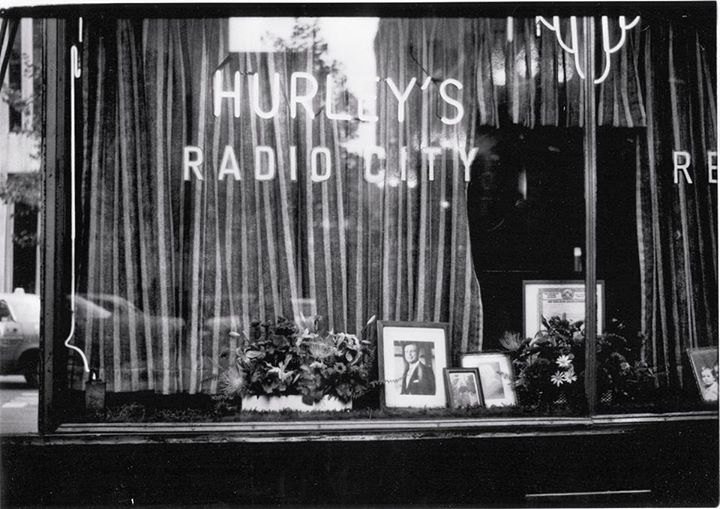

When Jack Paar Walked OUT, Here’s Where He Walked IN…

On April 10, 2014

- Archives, TV History

Notice the photo in the window of Jack Paar. Hurley’s was where Jack Paar went the night of February 11, 1960…the night he walked off the ‘Tonight’ when a network censor edited out one of his jokes from the previous night’s taped broadcast. Paar wasn’t really hiding, but didn’t want to be inside NBC or talk to the people calling him on the special NBC phone on the bar.

I think this picture was taken between February 11 and March 7, 1960 when Paar returned to the show. Thanks to Glenn Mack for this amazing photo which also happens to be the first and only photo of the original Hurley’s Bar that we know of.

On October 15, 1975, Hurley’s closing, after 70 plus years was covered on NBC’s ‘Tomorrow With Tom Snyder’. Below is the NBC description of that episode.

“This show marks the end of Hurley’s, a local bar on 49th Street in NYC frequented by NBC personalities and employees, which is closing after 70 years. This also begins the third year for the tomorrow show. Tom talks with Steve Allen about the changes that have taken place in New York. He feels a lot of the bad mouthing about the city is done by new yorkers. Then Dave Garroway, Jack Lescoulie and Frank Blair talk about the old days. They started with today on January 14 1952. Blair explains that he got up so early for the show by the time he got to Hurley’s it was his lunch time. Therefore he had a drink and furthered his reputation in that area. Comedians Bob & Ray and Ben Grauer talk with Tom about the days of radio and their transition to television. Kenny Delmar, Don Pardo, Bill Wendell and Lanny Ross tell stories of their careers. Hurleys was known as studio 1H or Hurley’s beach. There was an NBC phone on the bar where employees could be reached.”

“NBC Studio 1H”…Hurely’s Bar

On April 5, 2014

- Archives, TV History

“NBC Studio 1H”…Hurely’s Bar

As you can see in the photo below, Hurley’s Bar (which opened in 1892) was just a half a block away from NBC’s studio entrance, making it the nearest watering hole for everyone from stars to stage hands. It became the favorite for radio, television, newspaper and sports celebrities as well as tourists and midtown workers.

The old-fashioned saloon atmosphere, as well as the convenient location in Rockefeller Center, made Hurley’s a favorite. Liz Trotta noted “You never knew who would be standing next to your lifting elbow at Hurley’s. Jason Robards, Jonathan Winters, jazz musicians from the local clubs and the ‘Tonight’ show, starlets, football players, the lot.”

Johnny Carson made the Hurley name nationally familiar while he did his show live from Rockefeller Center. It was the bar in all of his Ed McMahon drinking jokes. David Letterman did several on-air visits to the bar. NBC technicians haunted the place so regularly that among themselves it was known as Studio 1-H.

Hurley’s was known as a place where status was left at the door. Mayor John Lindsay stopped in once, only to be hissed by the patrons. When Henry Kissinger and two bodyguards got noisy, they were ejected by the bartender “for rowdy behavior.”

But this is only half of a great “David & Goliath” story.

The bar had been here since 1892 and had always done well, even during prohibition when a florist shop was used to disguise the bar and it’s new back door.

In 1930, John D. Rockefeller, Jr. had begun aggressively buying up a staggering twenty-two acres of midtown property, right in the middle of Fifth Avenue’s most exclusive district, for a seemingly implausible project: Rockefeller Center. One by one he purchased buildings from Fifth to Sixth Avenue between 48th and 51st Streets. In the stranglehold of the Great Depression, none but the city’s wealthiest property owners could resist the offer to convert real estate to cash.

None except John F. Maxwell, grandson of John F. Boronowsky who owned the three story building at the opposite end of the block from Hurley’s and, of course, the feisty Irishmen themselves. In June 1931 Maxwell sent word to Rockefeller that he would not sell “at any price.”

Construction had already began on the gargantuan Art Deco complex of nineteen buildings on May 17, 1930. The block of 49th to 50th Streets, Sixth Avenue to 5th Avenue was eventually demolished, leaving only the two brick Victorian buildings standing on opposite corners of a devastated landscape.

The RCA Building—70 stories tall—rose around Hurley’s, diminishing the bar building only in height. But nothing in New York City is permanent and in 1979 Hurley Brothers and Daly was sold. Journalist William Safire spoke for New Yorkers in an article mourning the loss. The mahogany bar was removed to a Third Avenue restaurant and, as Nancy Arum wrote in her letter to New York Magazine that year “a pretend old-fashioned bar now stands where the real old-fashioned bar once was.”

The pretend old-fashioned bar took the name Hurley’s and, most likely, tourists never noticed the change. But proximity, tradition, or habit still brought the Rockefeller Center workers and celebrities into the bar until September 2, 1999. That night owner Adrien Barbey served the last glass of beer in the bar that had stood at Sixth Avenue and 49th Street for 102 years.

Today, Hurley’s is a bakery and the building at the other end of the block is a 9 West store. The 1931 photo on the right shows 6th Avenue with it’s elevated train (yellow). Hurely’s is in the red circle and 46th Street is in aqua. The other building left standing on the 6th Avenue corner is the space that is now a 9 West store. The 11 story NBC studio building is just behind Hurley’s.

The Amazing Life Of Eddie Brinkmann…Sullivan Stage Manager

On January 27, 2014

- Archives, TV History

Here is a great, four page story that covers 20+ years of ‘The Ed Sullivan Show’ from the guy that was the stage manger for the whole run, BUT HIS PERSONAL ARCHIVES ARE HERE, SO USE THE SEARCH FEATURE AT THE TOP RIGHT OF THE PAGE TO FIND THEM ALL!

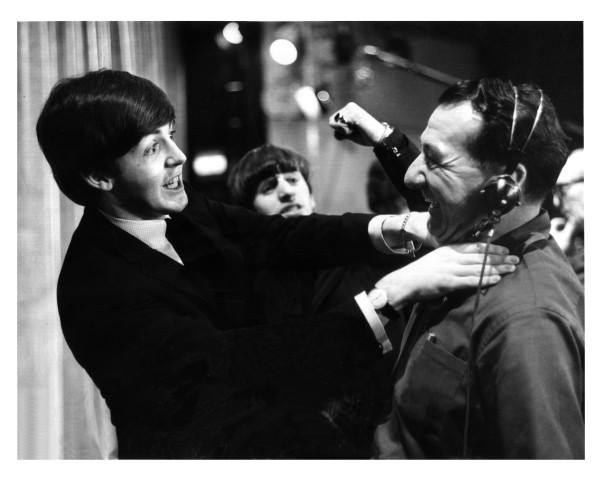

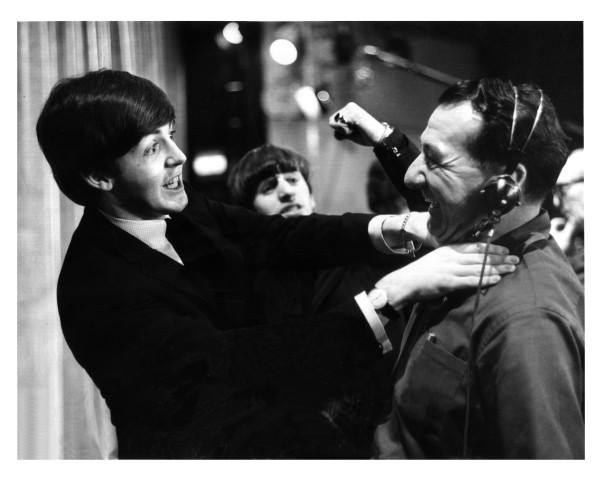

This is a one of a kind look behind the scenes of real television history as told by Eddie Brinkmann. Above, Brinkmann and McCartney playing around, letting of a little nervous energy before “the really big show”!

The First Camera Dolly, 1936

On January 20, 2014

- Archives, TV History

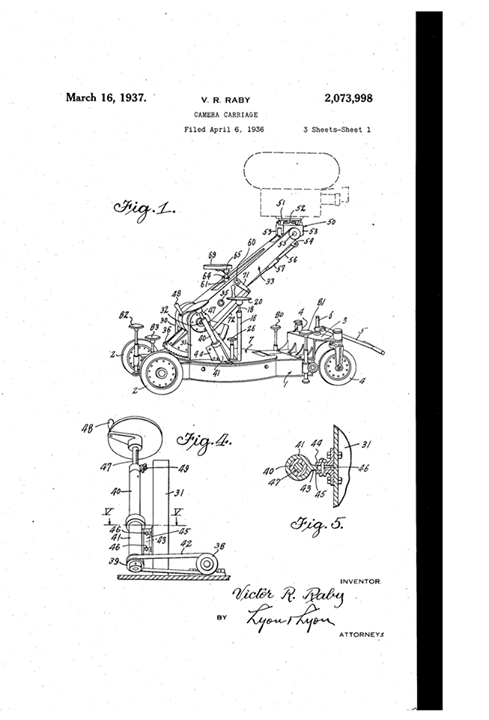

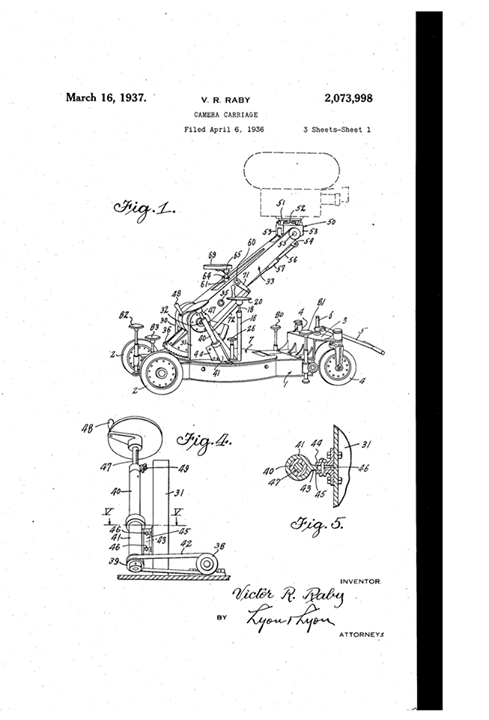

The First Camera Dolly, 1936

In the patent application, this is referred to as a “camera carriage” and as you can see, it has only three wheels. Designed by Victor Raby and made by Studio Equipment Company, these are now rare items and only a couple of these are still around. One of the survivors is shown below under a GE Iconoscope camera from WRGB and is located with the camera at the GE Museum in Schenectady NY. By early 1937, Fearless Camera Corp had introduced the four wheel Panoram dolly which was the preferred model. Television was still in the infancy stages so most customers were movie studios, but the WRGB crew has to be credited for being innovative.

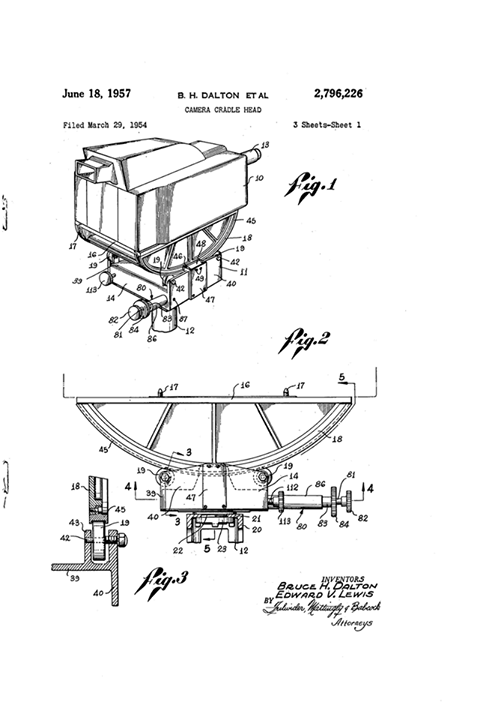

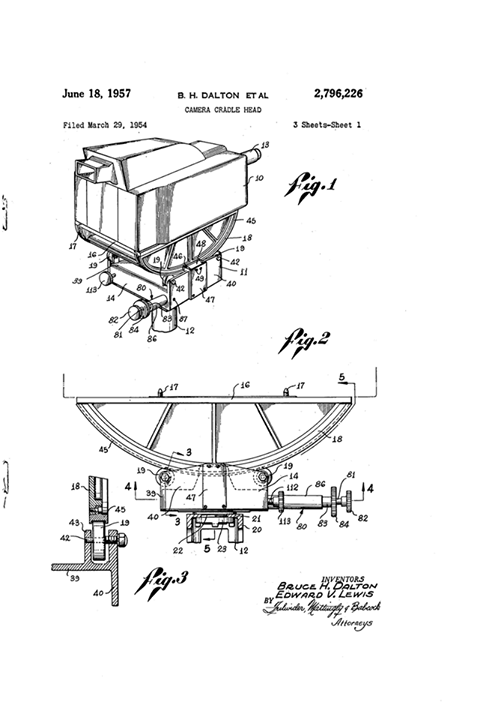

The Cradle Head Patent

On January 19, 2014

- Archives, TV History

Necessity Is The Mother Of Invention…The Cradle Head Patent

The Fearless Camera Company and RCA had a good thing going… Fearless (later, Houston Fearless) built the support equipment and RCA’s built the cameras and distributed for Fearless. As you can see in the photo on the right, the first experimental TK40 color cameras used the Fearless friction type pan head. The camera was just to heavy for it though, so Bruce Dalton (one of the creators of the TD 1 pedestal) and Edward Lewis came up with the now famous Cradle Head design. Although RCA built 239 TK40/41s, only 215 of these wide bodied cradle heads were made and distributed with the cameras as of 1964, when regular production stopped. In 1966, 24 more were made and all were shipped with the new Houston Fearless Cam style pan heads which you see under most of ABC’s TK41s as they bought 12 of the last 24 made. By late in 54 there was also a narrower cradle head available that fit under RCA’s black and white cameras like the TK11/31. The photo on the right shows one of the first production models of the TK40 being tested at the Colonial Theater.