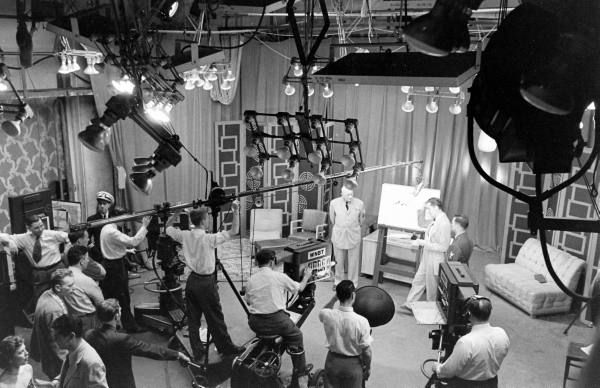

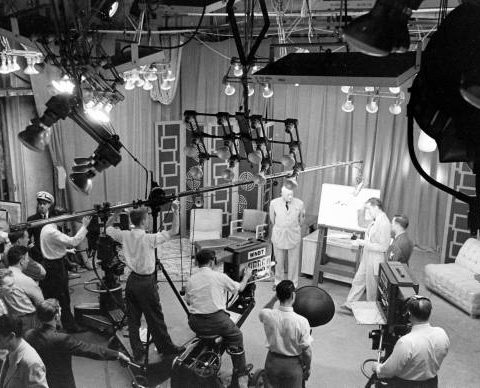

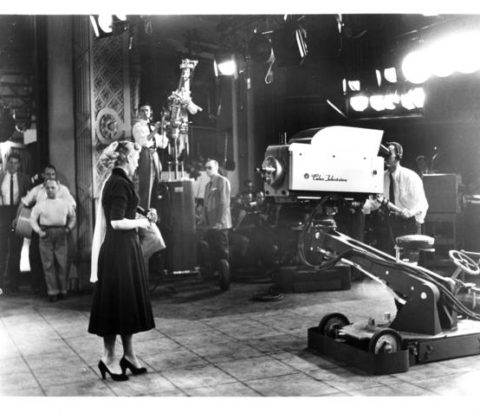

Ultra Rare…Inside NBC’s New York Studios 1950

As TV was taking off in 1950, NBC and others struggled to find studio space in New York. This rare film shows us, in more detail than we have ever seen, the course those efforts with a look inside not only the “Radio City” 30 Rock building, but also the International, Center and Hudson Theaters and thankfully, the “missing link” is shown here too…NBC’s Uptown Studios at 106th Street. There is a lot more here, including film of the NBC Kinescope department, the renovation of Studio 8H for TV, a new Master Control and much more. This film has been out of sight for decades but has now resurfaced, complete with narration by NBC’s first television news anchorman John Cameron Swayze.

A huge thanks to TV historian Alec Cumming and Ken Aymong at SNL for locating and preserving this fabulous NBC Studio history archive! -Bobby Ellerbee

First Person Oral History

This is an ongoing project, and from time to time, we will add audio interviews to this list, but here are the first of the series with a short, one line bio on each but their full story is in these hour long sessions. Enjoy!

1. George Sunga: Producer of Smothers Brothers, All In The Family, Good Times, The Jeffersons, Three’s Company and the first Production Director at CBS Television City. He handled all the Edward R. Murrow’s Person To Person live interviews from the west coast.

2 .Lou Bazin: His entire carrier as one of RCA’s top broadcast engineers includes development of the TK44-45-46, TK76, TKP 45 and much more

3.. Don Kennedy: As “Officer Don”, he was one of the nation’s top kid show host, as Don Kennedy he was an owner/operator of TV and Radio stations

4. Arch Luther: Chief Engineer of RCA’s Commercial Communications Systems Division and later, Vice President of Engineering for the RCA Broadcast Division

5. Jay Ballard: One of Television’s most respected engineering historians. Veteran NBC and ABC Labs, engineer extraordinaire and former associate of NBC/RCA engineering legend Fred Himelfarb.

EXCLUSIVE! 1963 Video Tour Of The Ed Sullivan Theater…A One Of A Kind Look Behind The Scenes

With many thanks to The University of Indiana Libraries Moving Image Archive, we are very happy and proud to be able to present an amazing piece of historic video that takes us, in two parts, first on a technical tour of CBS Studio 50, or as it is better known now; The Ed Sullivan Theater. CBS Director of Technical Services, Bob Hammer takes us from the stage, where we get a close look the Marconi Mark IV cameras, their lenses, pan heads and pedestals and to the mics and booms, all the way into the control room and even the equipment room for the most detailed look we have ever had of this historic broadcast facility. You’ll even see lens differences and Zoom demonstrations at the camera and in the control room, special effects wipes and how the cameras are shaded.

Here is Part 1

In Part 2, CBS’s Carlton Winkler, Director of Production Services leads a discussion on what this seminar is really about…production accounting, but it is not as dry as you might think! In this part you’ll see how the planning and budgeting bring about a full set that you will see erected in real time on the Sullivan stage. You’ll get to know what “above the line and below the line” costs are and a look at how the sets were built and then erected and perfected on stage, complete with a back screen projection unit adding to the reality of the scene. You’ll also see the rigging loft, stage and lighting details as this video alternates between lecture and two scenes that show the staging elements.

Here is Part 2

Originally, when this came to us from The Indiana University Libraries Moving Image Archive, this was one long presentation but thanks to our editing pro Jack Niesi (at NBC NY), we made two parts of it and were able through considerable editing (on the first part) to maximize Mr. Hammer’s oral delivery skills.

I would like to thank Jack for the long hours he spent on this project, but most especially, I want to thank or friend Dr. Mike Conway, who is a professor of Journalism at Indiana University for his help getting permission for us to use this video, as well as for writing “THE ORIGINS OF TELEVISION NEWS IN AMERICA”, which is THE BEST BOOK I have ever read on this subject.

I also wish to thank Carmel Curtis, Moving Image Curator at The University of Indiana for advocating for Eyes Of A Generation to present this information to you and to the Director of the Moving Image Archives for approving our display.

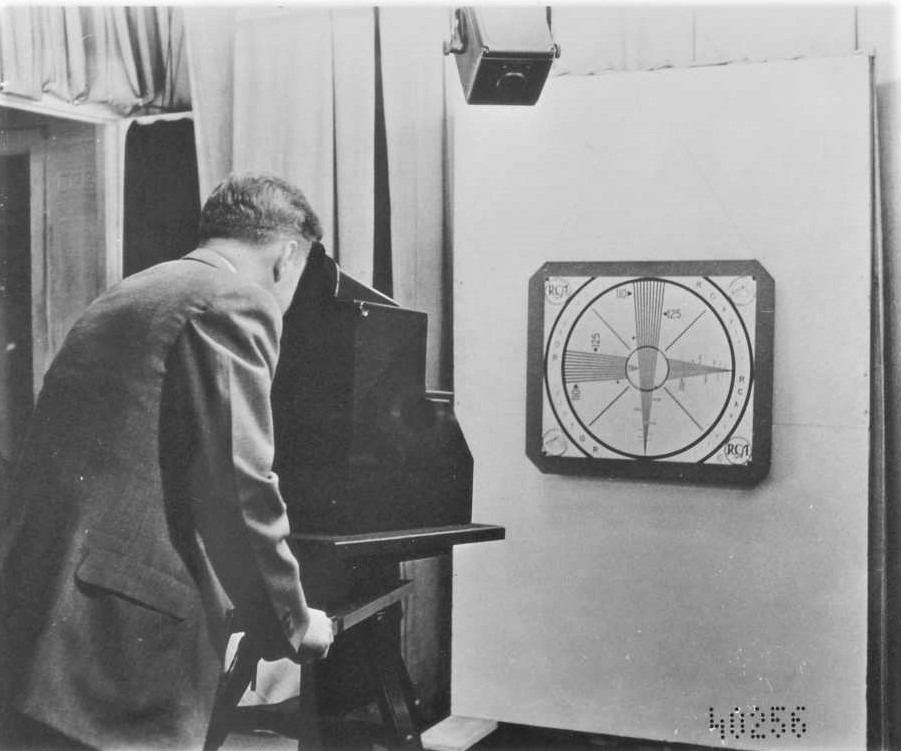

RCA’S FIRST ICONOSCOPE CAMERAS & THE PROTOTYPE

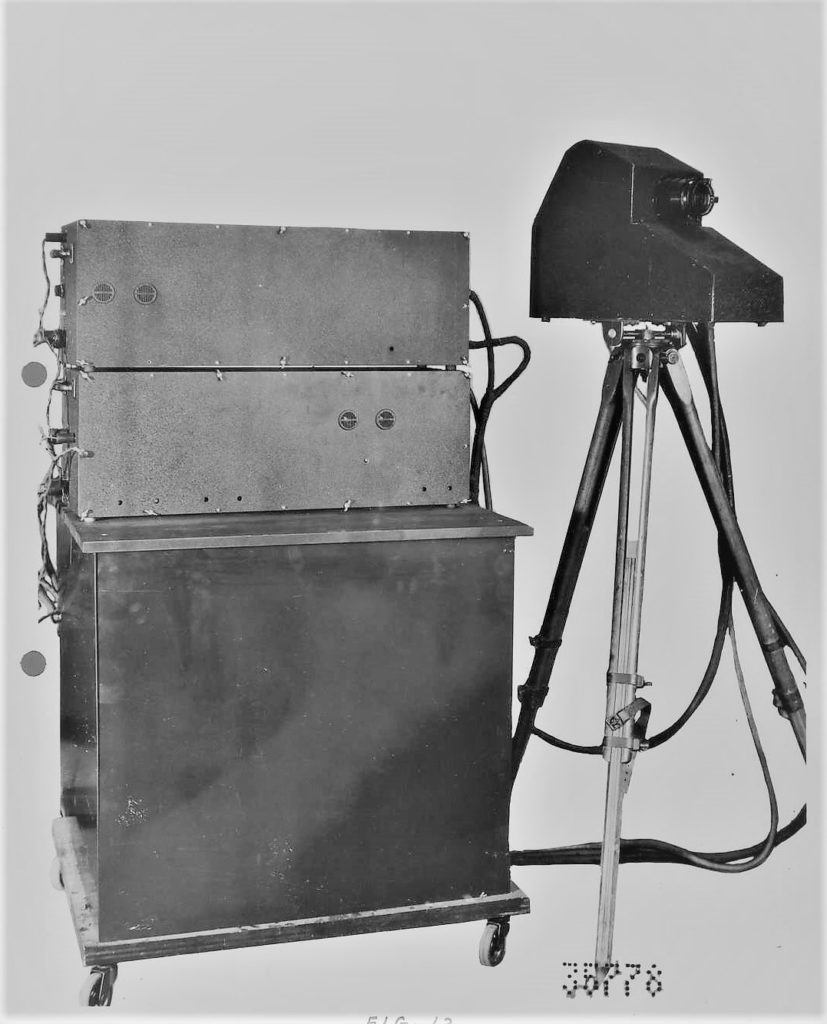

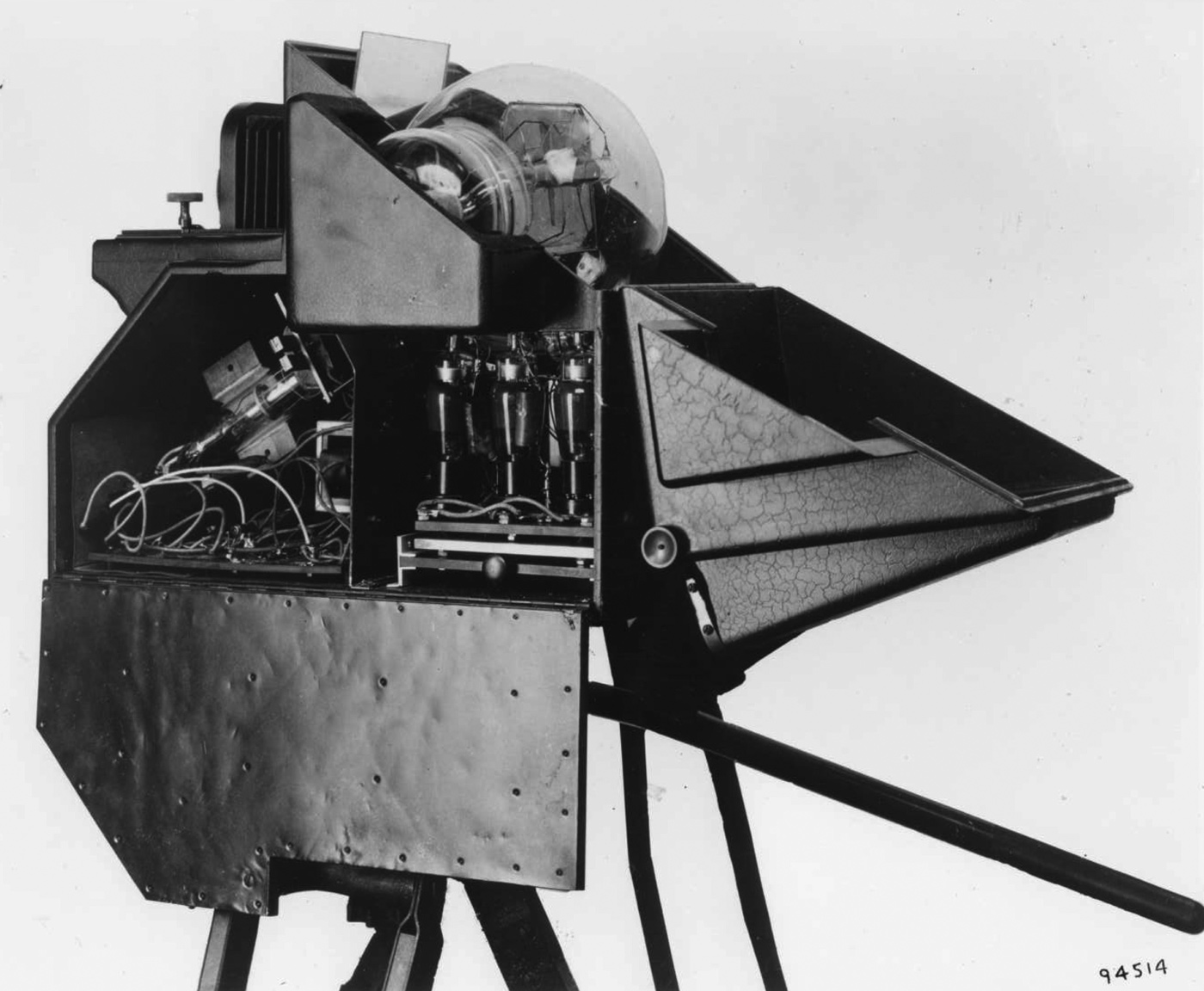

We will see three different Iconoscope cameras here…the first three all electronic cameras made by RCA at their Camden N.J. labs. These images are from the David Sarnoff Library Collection and are quite rare these days.

The first we’ll see will be the prototype camera developed by Dr. Zworykin around 1932. The second is a more sophisticated model that RCA introduced in 1934 and the last camera is the “icon” of early cameras, the one some refer to as the A500, which was first used in RCA/NBC experimental Studio 3H at Rockefeller Plaza. I would like to suggest that from here on out, we all refer to those hard-bodied cameras as the Studio 3H Iconoscope cameras.

RCA ICONOSCOPE PROTOTYPE CAMERA

If you look closely at the bottom of the camera, notice the rubber feet…items that suggest this sits on ‘something’ and we’ll see that something a few images down.

Below is the first ever shot of an electronic RCA TV camera with it’s camera control unit

Below is the paragraph from the RCA Broadcast News article (you’ll soon see) which describes the camera and configuration above, which is the original image that was photographed for the magazine article by Dr. Zworykin.

Here is the ‘something’ the camera sits on and the camera we see above is on the left. The unit it is sitting on is basically ‘the control room’ with all the components neatly packed together on this convenient rolling rack, so it is also a ‘remote unit’ of sorts since they can take it from lab to lab to experiment. Up top, in front of the camera there seems to be an experiment in progress as the prototype is shooting into a microscope with a light source shooting from the other side of the microscope’s slide table. Although this is an electronic system, it seems to have rotating mechanical disc at the light source, used for generating synchronizing pulses. As electronics progressed, less and less mechanical means were necessary to get a good stable image. It would be interesting to see the result of this experiment, which is possibly being conducted to see if there is a medical use for the new apparatus.

Before we move to the second camera, here is the August 1933 edition of the RCA Broadcast News magazine I mentioned with an 8 page paper on the new Iconoscope Tube by Dr. Vladimir Zworykin, the tube’s inventor. On pages 6 – 14 he describes the technology in detail and the image of the camera above is shown here on page 13 with it’s description on page 12.

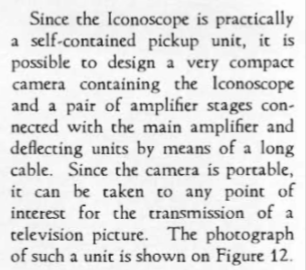

THE FIRST RCA ICONOSCOPE CAMERA

Above are two shots of the camera in testing at RCA’s Camden N.J. labs. Notice there is viewfinder on this model very similar to the kind you find on photographic cameras which is an optical viewfinder made of ground glass which captures the image from the lens.

![]()

Above left we see the interior in a nice clear shot and on the right a helpful labeling of the parts. We know the date of this camera because of the date on this photo from Dr. Zworykin’s photo albums that he kept at work to record events. This is RCA’s Lesley Florey in early tests to the camera in 1934 at Camden, but we think this was in use in 1933 too. Notice the tube is bubble shaped, but as resolution increased the tube became more drum like.

![]()

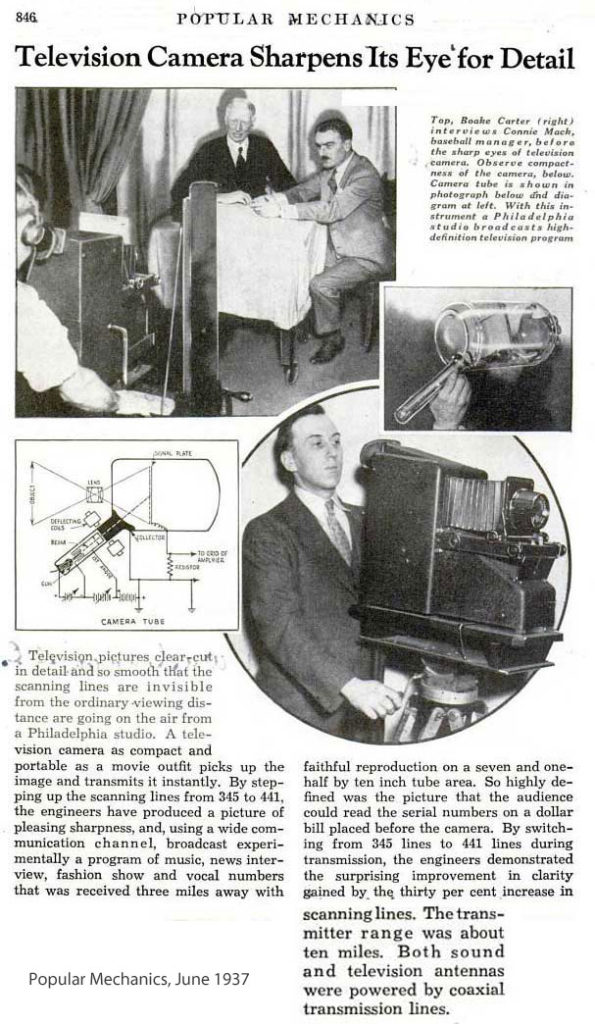

Below is a 1937 article that shows this same camera at Philadelphia experimental station W3XE which was owned by Philco. Philo Farnsworth was there in the mid 1930s, but competition was fierce and trade secrets were held close to the vest. Some former RCA engineers had come to work there in the early 1930s when RCA refused to sell any of their iconoscope tubes, and they began making their own tubes.

When RCA set up their experimental Studio 3H at Radio City in the spring of 1935, they had an all new camera design (which we’ll see next) and once 3H had been in operation for a while, Philco convinced RCA to sell them their bellows lens cameras (of which I believe there were two) to use in their W3XE station. Below is an article from 1937 that shows the RCA camera in use there. I included this image and info to help with any confusion with seeing the same camera at two different places.

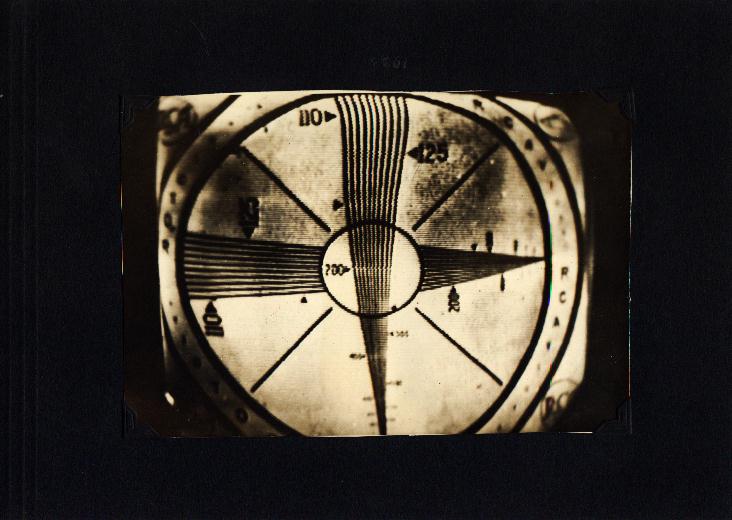

Above we see the camera shooting a test pattern in Camden and below, a transmitted image of this pattern in 1933.

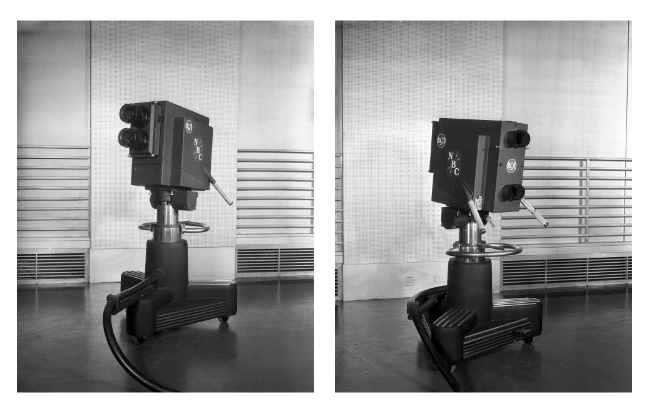

THE 1935 RCA STUDIO 3H ICONOSCOPE CAMERA

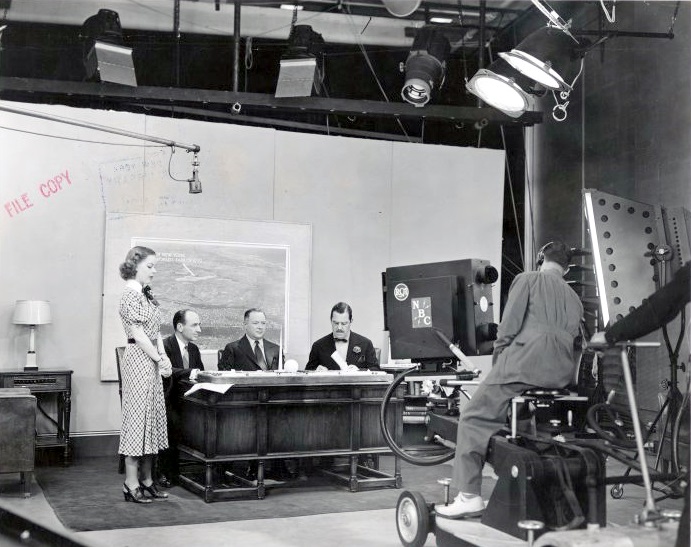

Above, the very first all electronic television studio…RCA Studio 3H at NBC’s 30 Rockefeller Plaza. In 1937, RCA transferred control of the studio to NBC Television, but until the mid 50s, there was usually some kind of testing going on in this space, along with programs originating here like Howdy Doody. As a matter of fact, when Howdy started December 27, 1947 the show was shot with these very cameras. Only after Studio 8G opened in June of ’48 did Studio 3H get three new RCA TK30 Image Orthicon cameras.

There were three of these hard bodied camera in Studio 3H and most of the time, at least one of the cameras was mounted on a Panoram dolly. In-fact the one shown here in the second image down may be a prototype as it has a nice wooden footrest/step up for the cameraman, the wheel base is longer and the rotating section is more centered in the chassis than the versions we see in the late ’40s and ’50s.

NOTICE AS WE GO! This is a “dating” trick of mine that gives me an idea when photos were taken. NOTICE on the photos above, there is a round RCA decal and below it is a square NBC decal, which are the original markings of these cameras. When you see that you know the photo was from about 1935 till 1937. After ’37, the round NBC decal was there and many times the second (or low viewfinder port) is sealed as in the image below.

Keep in mind, the camera bodies are the same three that were built in 1935…even the silver versions. All that changed was the internal workings and especially the Iconoscope tube’s resolution. These cameras started with 345 lines of resolution with their original dressing, then when they went to 441 lines, the camera art changed to the round NBC logo and the bottom viewfinder port was sealed. The silver on these cameras at NBC (and the ones they sold to CBS) occurred when the 525 line tubes came along on July 1, 1941.

The next image shows you the removeable lens plates that snap on and off for quick changes in the studio when a close up or wide shot is needed.

![]()

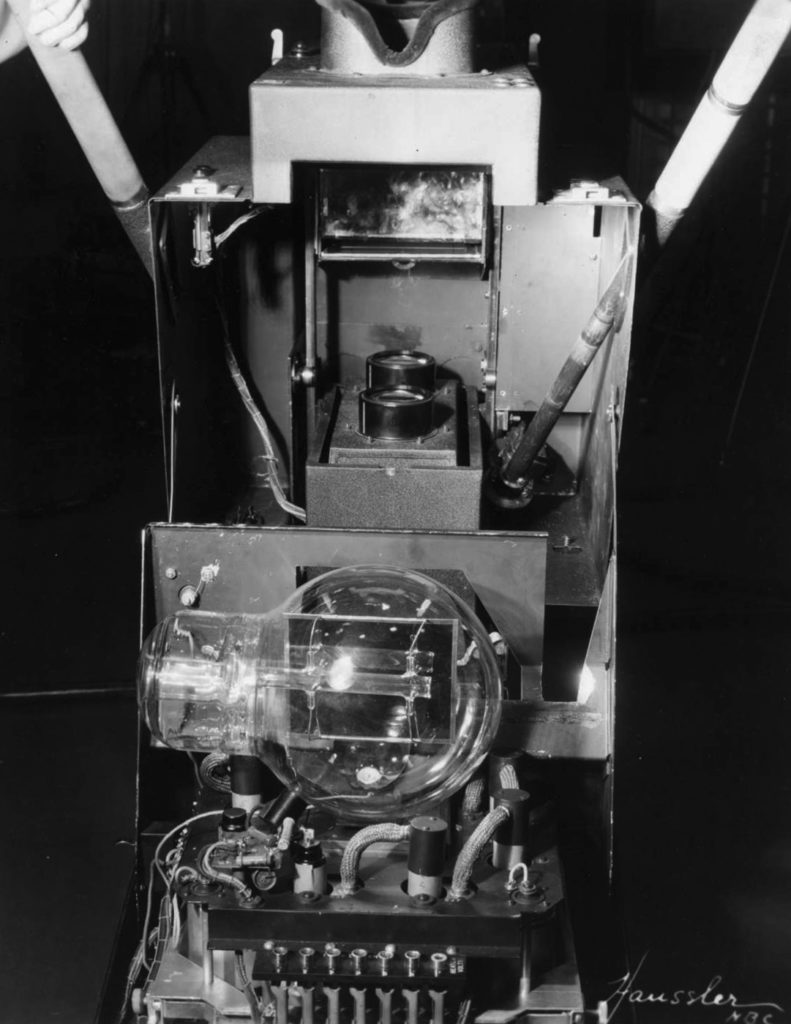

Here is the interior of the camera that shows you just how the optical (ground glass) viewfinder worked and where the tube was.

![]()

One of the big drawbacks to the optical viewfinder was the impossible upside down and backward image the cameraman had to deal with. To him, the voice command of left, meant right and up meant down!

![]()

In this image below, notice the 345 line Iconoscope tube is very bubble like which marks this as the original tube style in these cameras. If you are confused, these opened from the back and tilted up to get to the interior components.

Notice in the image below, the bottom viewfinder port is gone and the Iconoscope tube is now the very familiar drum shaped tube we think of as the “normal” shape for these instruments. This image may be from around 1939 and shows a 441 line resolution setup.

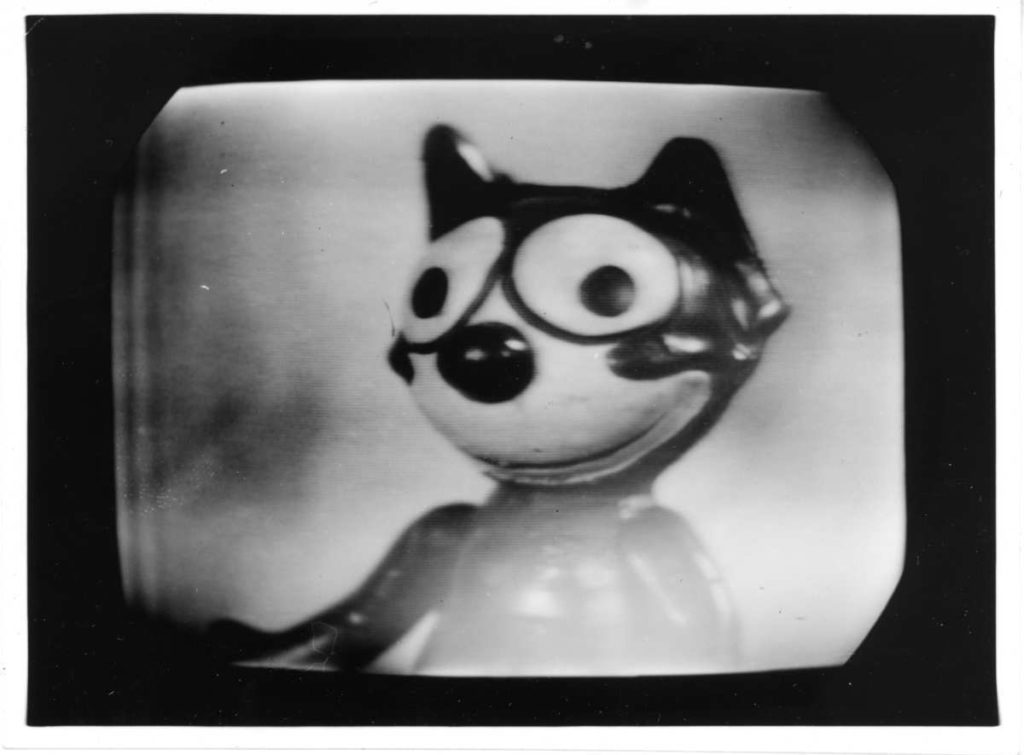

If you thought Felix The Cat camera models went out with mechanical television, think again! Here is a photo shot off the monitor in Studio 3H on February 5, 1937 showing how he looked with the new 441 lines of resolution.

Below, the final step as the camera bodies are painted silver to denote the upgrade in resolution to 525 lines of resolution and this is a good look at the 1850A style six inch iconoscope tube.

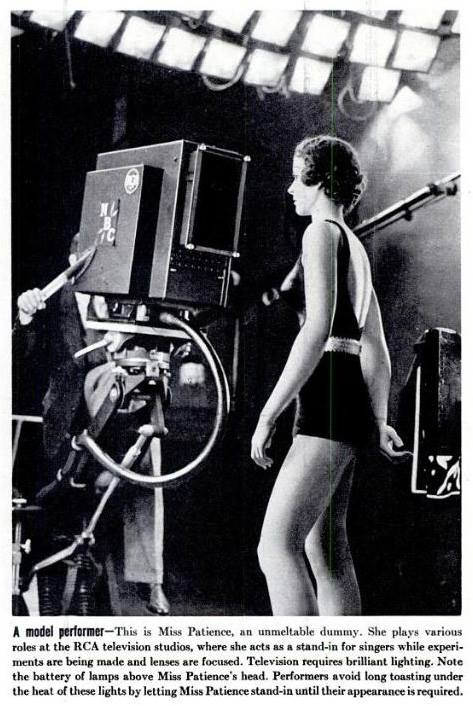

Here are our last images which show up top, a 1941 “Miss Legs” contest and below, an early necessity in Studio 3H…Miss Patience, a mannequin that acts as a stand in under the blistering light needed for the iconoscope.

Shooting Live TV Shows On Film By Karl Freund; “I Love Lucy” Director of Photography

Below this 1953 SMPTE article written by Karl Freund is a copy of his biography by IMBD writer John Hopwood. In the article Freund tells how he shot I Love Lucy and describes how he overcame unique new problems.

Karl Freund was born in Germany in 1890; by age 15 was working as a projectionist and by age 17, he had become a newsreel photographer. By 1926, he had earned a reputation for his skills in cinematography and his work on the classic Metropolis was his last job there before leaving for America.

Now possessing an international reputation, Freund emigrated to the U.S. in 1929, where he was employed by the Technicolor Co. to help perfect its color process. Subsequently, he was hired as a cinematographer and director by Universal Studios, where he cut his teeth, uncredited, as a cinematographer on the great anti-war classic All Quiet on the Western Front (1930), Universal’s first Oscar winner as Best Picture.

Universal’s bread and butter in the early 1930s were its horror films, and Freund was involved in the production of several classics. Among his Universal assignments, Freund shot Dracula (1931) and Murders in the Rue Morgue (1932), and directed The Mummy (1932). The Mummy (1932) was Freund’s first directorial effort, and co-star Zita Johann, who disliked Freund, claimed he was incompetent, which is unfair, seeing as how the film is now considered a classic of its genre. The film uses the undead sorcerer Imhotep’s pool with which he can impose his will over the living by spreading some tana leaves on the water, as a visual metaphor for the subconscious. The film is arresting visually due to Freund’s cinematic eye that created a sense of “otherness.” The film is infused with a dream-like state that seems rooted in the subconscious mind. Freund’s other directorial efforts at Universal proved less satisfying.

MGM wanted Freund for his genius at camera work. He shot the rooftop numbers for The Great Ziegfeld (1936), another Best Picture Oscar winner, and worked with William H. Daniels, Garbo’s favorite cameraman, on “Camille” (1936). He shot Greta Garbo’s Conquest (1937) solo, though he never worked with Garbo again. That same year, he was the director of photography on The Good Earth (1937), for which he won an Academy Award for Best Cinematography.

Other major MGM pictures he shot were Pride and Prejudice (1940), for which he received an Academy Award nomination, Tortilla Flat (1942), and A Guy Named Joe (1943). He also worked for other studios, shooting Golden Boy (1939) for Columbia. In 1942, he pulled off a rare double: he was nominated for Best Cinematography in both the black and white and color categories, for The Chocolate Soldier (1941) and Blossoms in the Dust (1941), respectively.

One of the last films he shot for MGM was Two Smart People (1946), starring Lucille Ball. In 1947, he moved on to Warner Bros, where he shot the classic Key Largo (1948) for John Huston. His last film as a director of photography was Michael Curtiz’ Montana (1950), which starred Gary Cooper.

Always the technical innovator, Freund founded the Photo Research Corp. in 1944, a laboratory for the development of new cinematographic techniques and equipment. His technical work culminated in his receipt of a Class II Technical Award in 1955 from the Motion Pictures Arts & Sciences for the design of a direct-reading light meter which is seen in the PDF article on this page. That same year, he had the honor of representing his adopted country at the International Conference on Illumination in Zurich, Switzerland.

It was perhaps inevitable that the technical and innovation-minded Freund would get to work for a brand new visual medium, television. Lucille Ball, whom he had photographed when she was a contract player at MGM, became his boss when he was hired as the director of photography at Desilu Productions, owned by Ball and her husband, Desi Arnaz. Desilu hired the great Freund as its owners were determined to shoot the show I Love Lucy (1951) on film rather than produce the show live, as was standard in the early 1950s. Most shows were shot live, while a film of the program was simultaneously shot from a monitor, a process that created a “kinescope.” The kinescope would be shown in other time zones on the network’s affiliates. Desilu’s owners disliked the quality of kinescopes, and needed Freund to come up with a solution to their problem of how to maintain the intimacy of a live show on film.

Freund agreed that the show should be shot on film rather than live, as film enabled thorough planning and allowed for cutting, which was impossible with live TV. Freud knew that film would allow Desilu to eliminate the fluffs which were a staple of early television, and would allow the producers to re-shoot scenes to improve the show, if needed.

I Love Lucy had to be filmed before an audience to retain the immediacy of a live TV show, which meant that the traditional, time-consuming methods of studio production with one camera would not work. Freund decided to shoot I Love Lucy with three 35mm Mitchell BNC cameras, one of each to simultaneously shoot long shots, medium shots and close-ups. Thus, the editor would have adequate coverage to create the 22 minutes of footage needed for a half-hour commercial network show.

The then-innovative, now-standard technique of simultaneously shooting a situation comedy with three 35mm cameras cut the production time needed to produce a 22-minute program to one-hour. The cameras were mounted on dollies, with the center camera outfitted with a 40mm wide-angle lens, and the side cameras outfitted with 3- and 4-inch lenses. The resulting shots were edited on a Movieola. A script girl in a booth overlooking the stage cued the camera operators. Due to extensive rehearsal time before the show was shot live, the camera operators had floor marks to guide them, but Freund’s system was enabled by the script girl overseeing their actions via a 2-way intercom. The system made the shooting, breaking-down, and setting-up process for the next scenes on the three sets of the I Love Lucy (1951) stage very economical in terms of time, averaging one and one-half minutes between shots.

Freund worked out the lighting during the rehearsal period. Almost all of the lighting was overhead, except for portable fill lights mounted above the matte box on each camera. In Freund’s system, there were no lighting changes during shooting, other than the use of a dimming board. Since the lighting was mounted overhead on catwalks, power cables were kept off the floor, which facilitated the dollying that was essential for making the system work fluidly.

Freund’s solution to the problem of shooting a show on film economically was to make lighting as uniform as possible, taking advantage of adding highlights whenever possible, since a comedy show required high-key illumination. Due to the high contrast of the tubes in the image pickup systems at the television stations, contrast was a potential problem, as any contrast in the film would be exaggerated upon transmission of the film. To keep the film contrast to what Freund called a “fine medium,” the sets were painted in various shades of gray. Props and costumes also were gray to promote a uniformity of color and tone that would not defeat Freund’s carefully devised illumination scheme.

In a typical workweek, the I Love Lucy (1951) company engaged in pre-production planning and rehearsals on Monday through Thursday. I Love Lucy (1951) was filmed before a live audience at 8:00 o’clock PM on Friday evenings, and Freund’s camera crew worked only on that Friday and the preceding Thursday. Freund, however, attended the Wednesday afternoon rehearsal of the cast to study the movements of the players around the sets, noting the blocking and their entrances and exits, in order to plan his lighting and camera work. Thursday morning at 8:00 o’clock AM, Freund and the gaffers would begin lighting the sets, which typically would be done by noon, the time the camera crew was required to report on set to be briefed on camera movements. Then, Freund would rehearse the camera action in order to make necessary changes in the lighting and the dollying of the cameras.

It was during the Thursday full-crew rehearsal that the cues for the dimmer operator were set, and the floor was marked to indicate the cameras’ positions for various shots. For each shot, the focus was pre-measured and noted for each camera position with chalk marks on the stage floor. Another rehearsal was held at 4:30 PM with the full production crew. Though a full-dress rehearsal was held at 7:30 PM, with the attendance of the full crew, the cameras were not brought onto the set. The director would take the opportunity to discuss the plan of the show and solicit input from the cast and crew on how to tighten the show and improve its pacing.

The next call for the entire company was at 1:00 PM on Friday to discuss any major changes that were discussed the previous night. After this meeting, the cameras would be brought out onto the stage, and at 4:30 PM, there would be a final dress rehearsal during which Freund would check his lighting and make any required changes.

After a dinner break, the cast and production crew would hold a “talk through” of the show to solicit further suggestions and solve any remaining problems. At 8:00 PM, the cast and production crew were ready to start filming the show before a live audience. Before shooting, one of the cast or a member of the company had briefed the audience on the filming procedure, emphasizing the need for the audience’s reactions to be spontaneous and natural.

Shooting was over in about an hour due to the rapid set-ups and break-downs of the crew, which shot the show in chronological order. Due to the thorough planning and rehearsals, retakes were seldom necessary. Camera operators in Freund’s system had to make each take the right way the first time, every time, to keep the system working smoothly, and they did. An average of 7,500 feet of film was shot for each show at a cost that was significantly less than a comparable major studio production.

Freund also served as the cinematographer on the TV series Our Miss Brooks (1952), which was shot at Desilu Studios, and Desilu’s own December Bride (1954). It was no accident that Desilu productions turned to Karl Freund to realize their dream of creating a high-quality show on film. Freund had the broadest experience of any cameraman of his stature, starting in silent pictures, and then excelling in both B&W and color in the sound era. With his penchant for technical innovation, he was the ideal man to develop solutions for filming a television show. Freund met the challenge of creating high quality filmed images in a young medium still handicapped by its primitive technology.

Freund became the dean of cinematographers in a new medium, with Desilu’s I Love Lucy and its other shows recognized as the gold standard for TV production. His work ensured the fortunes of Desilu Productions, and the personal fortunes of Desilu owners Desi Arnaz and Lucille Ball, as he provided them with quality films of each show that could be easily syndicated into perpetuity, whereas the live shows filmed secondarily off of flickering TV monitors as kinescopes could not.

After retiring as a cinematographer, Freund continued his research at the Photo Research Corp. He died on May 3, 1969.

– IMDb Mini Biography By: Jon C. Hopwood

4 Minutes Of RCA/NBC Color With TK41s

This is part of the original 26 minute RCA presentation from 1956 that pitches color to the public. The full length version is linked below, but this it the good part if you (like me) love TK41s. It is such a rare occasion to see the great giants in action, that I thought it would be great just to cut to the chase here. ENJOY! -Bobby Ellerbee

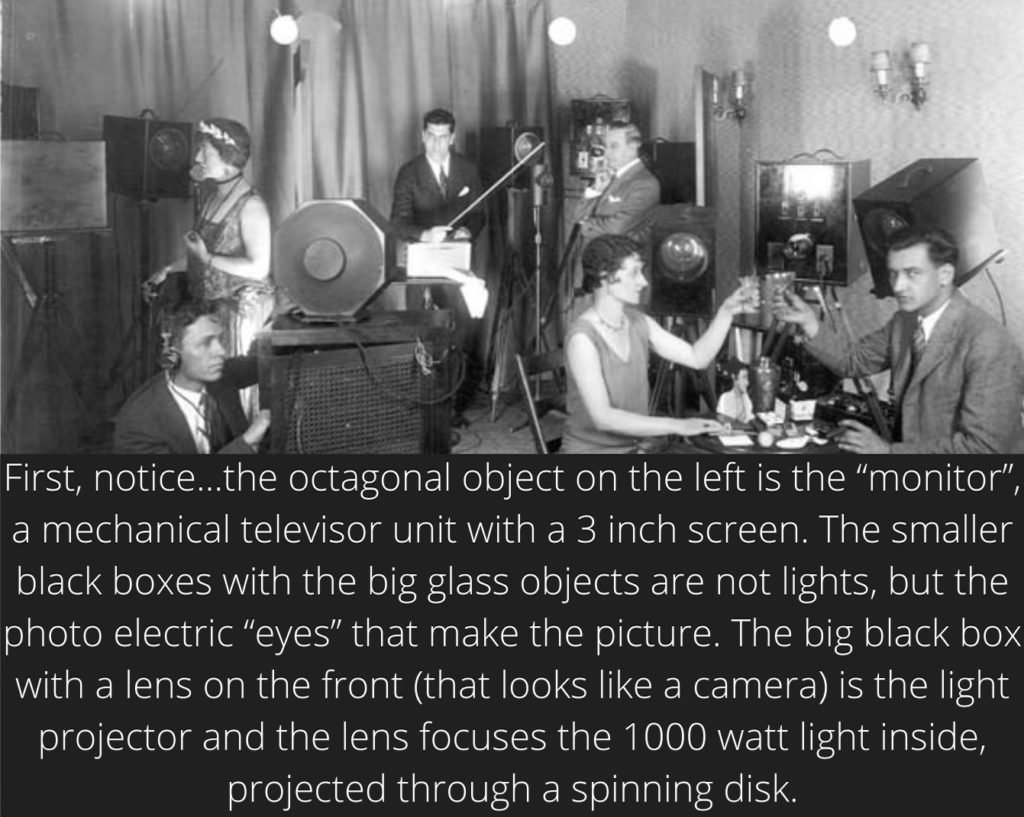

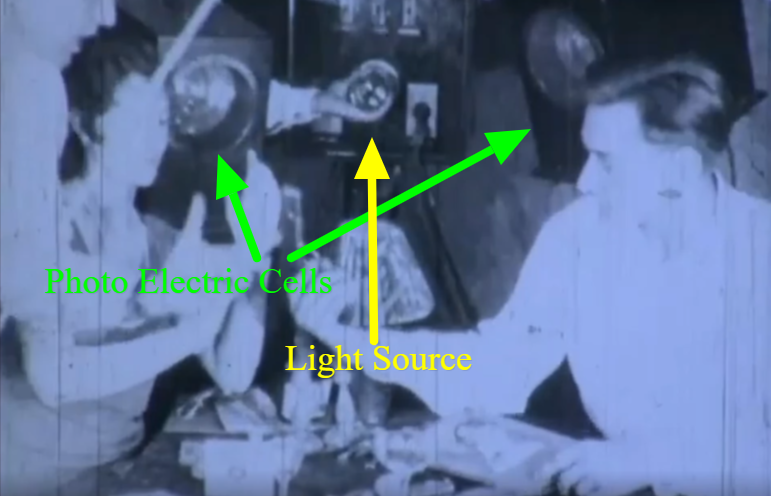

Rare: Mechanical Broadcast of TV’s First Drama, The Queen’s Messenger

This is part of the first ever dramatic television broadcast called “The Queen’s Messenger” and what you are seeing in this clip below is how they shot a close up scene that concentrated on the actors hands, and what they had in them. The experiment was broadcast by GE’s Schenectady, New York television station W2XB and radio their station WGY, on September 11, 1928. It was a radio drama adapted for television and broadcast both sound and moving pictures. These were received by televisions with screens that were three inches in diameter that were set up in various places all around the city. There were special effect props for this broadcast to enhance the actors’ performance and their sounds.

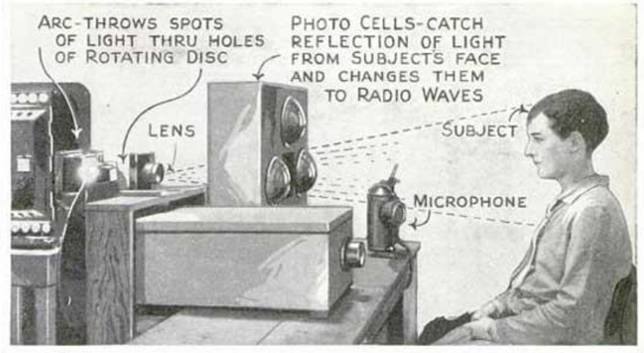

There were only four actors, these two hand actors (on the right) and two face actors…a female Russian spy and a male British diplomatic courier. Only close ups were possible and there were three light projectors in the room with six photo electric cell boxes. One light projector was for the female face actor, one for the male face actor and one for the hand actors.

By the way, this is a brightly lit reenactment for the film camera, because the studio had to be twilight dark in order for the not so sensitive photo electric cells to capture the 24 lines of light projected onto the subjects.

Just to be clear, here are the elements that you just saw in the film clip.

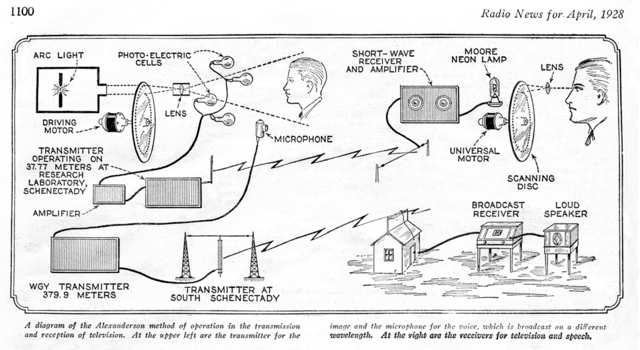

Also shown here is an April 1928 diagram of the GE mechanical television process that includes the broadcast and reception method. Notice that two radio transmitters were used in these experimental broadcasts. The visual image was broadcast on GE’s experimental shortwave station W2XB operating on 37.33 meters (7.7 MHz) and the sound was broadcast over their radio station WGY, operating on 379.9 meters (790 KHz).

The last image is a simplified version of the broadcast apparatus from an April 1928 Mechanic’s Illustrated.

January 6, 1952…First Ever “TODAY” Promo

First Ever “TODAY” Promo, Live With Fred Allen & Dave Garroway

In preparation for a new era of television, the full staff of the new “TODAY” show began reporting to work at 4 AM, Monday January 2, 1952, to get them acclimated to their new early morning schedules, two weeks prior to the January 14th debut. This sketch/promo aired at the end of that first early rising week, on Friday night, the 6th.

This is also a rare look at “Sound Off”, a show that had rotating hosts that included not only radio star Fred Allen, seen here, but Bob Hope and Jerry Lester as well. The show only aired for a few months, and this is one of the last episodes. The announcer is Dick Stark.

I think this show came from NBC’s Uptown studios at 106 Street. Notice in the front of the gag, CBS gets dished and the “NBC Man” is called Mr. Weaver, a poke at NBC program head Pat Weaver, who of course was the creator of “Today”, “Tonight” and much more. -Bobby Ellerbee

TODAY Show Debut

It was 7 AM, January 14, 1952 when TODAY debuted on NBC. There were of course a number of innovations that came from the show, but on Day 1, it seems to me that they are already pushing the envelope with a lower third news crawl at the bottom of the screen…AND a time bug which pop in at the 2:15 mark! A television first for a daily news and entertainment program.

Inside NBC Like You Have Never Seen! Pristine “Behind Your Radio Dial” Video

About five years ago, I found this classic 1948 movie short on YouTube. It was a bad dub of a bad dub, but at least it was a rare glimpse into the history of NBC when radio was king and TV was just getting started.

As a matter of fact, this film gives us the only video record of NBC Studio 8G in action with it’s unique NBC built Image Orthicon cameras in use(https://eyesofageneration.com/the-nbc-nd-8g-cameras/)

The show they are broadcasting is television’s first non-scripted entertainment show, “Hourglass”. When you see the unusual looking cameras and the acrobatic, dancing Costello Sisters in their mini costumes, you’ll be one of the few people to not only have seen this show, but also to know what the show is and who the dancers are. https://eyesofageneration.com/?s=hourglass

I was fascinated by all the studio and building décor we were seeing…places and features that were no longer there…overcome by the march of time and the need for space to evolve at 30 Rockefeller Plaza. Before I posted the video back then, I sent a link to Joel Spector and Dennis Degan; two NBC friends that have spent decades waking these halls and noting the changes. We compared notes and I compiled a written narrative that timed with the who, what and where we were seeing on the screen.

A year later, Matias Bombal contacted me and told me he had just located at pristine copy of the 1948 movie short “Behind Your Radio Dial” there in California. His efforts led to the digitizing of that print, but he thought it would be a shame to clutter it up with “lower third” graphics and explanations on screen, so…he narrated and enlarged upon what we are seeing using his own research and updated notes from myself, Joel and Dennis.

In the top video presentation, Matias does a masterful job of narrating and showing us what we will see in the second, or bottom video presentation, which is the completely digitized, HD version of the 35 millimeter print he found in California. Our great thanks to Matias Bambal and all the people that helped find and digitize this and to NBC veterans Joel Spector and Dennis Degan. ENJOY! -Bobby Ellerbee

The Introduction:

Below “Behind Your Radio Dial” The Movie Short:

CBS Portable Prototype In Action, 1962 Belmont Stakes & ’63 Beatles Miami

There are two videos here. The first is a great look at the first CBS portable and wireless camera developed in 1961-62 by CBS VP of Technology Dr. Joe Flaherty with help from Ikegami. There were three prototypes with one at CBS O&O KMOX in St. Louis to test for use as an “electronic new gathering” tool, one was at CBS New York for the same and more bench testing and one was assigned to the Florida bound CBS mobile units covering the many manned space missions, at the then, Cape Canaveral.

This footage at the race tracks is a perfect example of the kind of tests they subjected the camera to, and it was also brought on stage for a live demonstration during an Ed Sullivan show, I think, just a few weeks after the Belmont Stakes with Dr. Joe and a couple of the Ikegami engineers introduced during the demo.

With reference to the top photo of The Beatles on stage during the Sullivan’s live Miami show , see the image clarity that this camera makes as he shoots Ringo from a low angle (at :32 and 1:41), just like in the photo. Nice, crisp picture, just like the TK30s are giving us as, I think, they are both using the same 3.5″ image orthicon tube. Thanks to Kevin O’Keefe for the Belmont video.

RCA Television Tape Equipment & Prices, 1966

A trip down memory lane when 4 heads were better than one, and quad editing was just getting started. Here is the 83 page catalog with prices on the last few pages.

RCA TR 4 Video Tape Machine Demo

This 1966 RCA demo on how their newest quad machine works is hosted by RCA’s John Wentworth and although the quality of the film capture is not a good as we would like it, the technical presentation is about as good as it gets. The TR-4 cost over $35,000 in 1966, equivalent to over $283,300 in 2021.

The BEST JOB In Live Television?

If you guessed “anything” at Saturday Night Live, you’d be 99% right, but only one job in the world is the absolute “best”. Operating Camera 1 on the Chapman Electra crane in NBC Studio 8H is the hands down winner and although seeing a video is not the same as being there, this sure goes a long way!

I’ve actually had the pleasure of being there as the crane crew’s guest and I am forever impressed with these four gents and their performance. Many thanks to John, Phil, Louis and Bob, and now Michael too! Open the video and meet them. For MUCH MORE on the historic Chapman Electra crane, go here!

https://eyesofageneration.com/teletales/studio-8h-and-the-chapman-crane/

Viewseum

The Viewseum is a portal for viewing things that belong in a museum of rare moving images…all gathered in a central location. These videos and curated photographs have been collected to tell a story of television in action. This is a living history of broadcasting that spans the decades, as far back as the first transmissions, to the latest in the network studios and everything in between. There are video tours of historic TV landmarks, moving image stories about the first studios, first cameras, first color, first videotape and a hundred surprises that come in every shape form and fashion.

NBC First Television Broadcast…July 7, 1936

The First All Electronic Television Broadcast by RCA & NBC, July 7, 1936

The Television History Part

The video here was shot by a Pathe film camera on July 7, 1936…the day that RCA’s all electronic experimental television system was first demonstrated to an audience of people other than RCA and NBC engineers. Although the 225 invited guests this day were licencees of RCA and radio station owners that were NBC affiliates, they were still people that had only heard about this new thing called television. A news report described it this way: At David Sarnoff’s request for an experiment of RCA’s electronic television technology, NBC’s first attempt at actual programming is a 30-minute variety show featuring speeches, dance ensembles, monologues, vocal numbers, and film clips.

Just one week earlier, on June 29, 1936, television broadcast station W2XF began operation in the Empire State Building on an experimental basis for public reception. Although the signal was broadcast to the public, they had no way to receive the pictures since only RCA engineers had all of the 80 plus receivers in their homes and offices.

Further down, I’ll go into detail of who we are seeing and hearing in the film of that first day of broadcasting from Studio 3H, but first a little on what they actually saw when they looked at the screens of the 80 or so receivers in the 67th floor viewing room at 30 Rockefeller Plaza.

NBC chief engineer O.B, Hansen and his men were having serious noise problems in the amplifiers until just a few hours before the big July 7 broadcast, when they managed to solve the problem. Since white phosphorus was not yet available to use in picture tubes, these guests were seeing green phosphorus images on 9 inch round tubes with 5 by 7 inch masks…too small for most, but that’s what they had. The images were 343 line resolution “high definition” pictures on sets with 33 tubes and 14 controls.

Notice the announcer identifies the station as W2XF and not W2XBS. RCA’s earliest experimental TV transmitter was located at the Van Cortlandt Park research facility and in 1928 was designated W2XBS. The transmitter and the W2XBS designation moved to the New Amsterdam Theater on 42nd Street in 1930. The first tests on that transmitter from both locations featured the famous Felix The Cat image broadcast via the Nipkow Disc mechanical system.

The W2XF license belonged to Western Electric and Bell Labs, which early on became part of RCA. When the Empire State Building transmission facility came online 1935, that set of call letters was used, but within a couple of years, the calls went back to W2XBS and eventually became WNBT and is now WNBC. Many thanks to Frank Decker for his research into this area which you can see more of at http://w2xf.com/

What We See Here

As we get our first ever recorded look inside television’s very first all electronic studio, we see a single RCA Iconoscope camera most likely manned by NBC’s first cameraman, Albert W. Protzman. His utility man (kneeling) may be the great Heino Ripp.

On the set, on the right of course is RCA president David Sarnoff and on the left is General James Harbord who was then chairman of the board of RCA and remained so until 1947.

The next man to sit with Mr. Sarnoff is NBC president Lennox Lohr and the conversation turns to the new coaxial cable from 30 Rockefeller Plaza to the new transmitter atop the Empire State Building and to the viewing party about to start on the 67th floor.

Here we cut to film shot atop 30 Rock that same day with the new antenna in the background on the Empire State Building. As these men are introduced, remember that Mr. Sarnoff has invited the radio station owners, who are all NBC affiliates, because he wants them to immediately begin their applications for television licences for their city…to get ahead of the crowd.

(FYI, aside from the portion mentioned above, I have edited most of the other Pathe film inserts out of this to concentrate on the historic live performance in the studio. Television’s First!)

When the fashion show starts, you will hear the voice of television’s first ever female announcer…Betty Goodwin. Betty had been a newspaper reporter in Seattle, but moved to NYC in the depths of the depression to take a job in radio with NBC. After working as a production assistant at the 1936 political conventions, she was reassigned to kind of the same position in the new Television Department, which at the time was very hush-hush.

When RCA set up the experimental Studio 3H in 1935, they had kept it under wraps as competition for tech secrets was fierce. By July of ’36, RCA had decided to go public with their project, and on July 7, their first public broadcast was made from this studio for a group of radio station owners, which were NBC affiliates, watching on the 62nd floor of 30 Rock.

Next, we see the first people of color ever to appear on television. Eddie Green, a popular stage, radio and screen comedian and George Wiltshire, a well known straight man to many entertainers.

Next up, a trio of the Radio City Music Hall dancers, The Rockettes, perform a specially choreographed tap dance number.

They are followed by Broadway star Henry Hull recreating a scene from “Tobacco Road”. Hull’s greatest success as an actor was on Broadway in his portrayal of Erskine Caldwell’s Jeeter in “Tobacco Road,” which still ranks among the longest-running dramas in the Great White Way’s history, opening on December 4, 1933, and closing on May 31, 1941, after 3,182 total performances.

The singing girls that follow Hull were southern belles from Georgia, taught to harmonize by their mother. Their father, a wealthy cotton broker, loved to accompany them on piano. In the early 1930s, they moved to New York’s Park Avenue and became involved in New York, Long Island and Newport Society. A search was on at the time to find female trios to compete with the popular Boswell Sisters. The Pickenses were spotted at a party and quickly landed both a radio deal and a recording contract.

Their radio shows ran from 1932 through 1936 and they appeared in several films and in the Ziegfeld Follies of 1936.

Finishing off the broadcast is Ed Wynn, who seems slightly befuddled with the whole thing as there is no audience to play to. He is accompanied by the famous NBC radio announcer Graham McNamee.

Winn was an accomplished vaudeville comedian before he became a fixture on NBC radio when he hosted the popular radio show The Fire Chief, heard in North America on Tuesday nights, sponsored by Texaco gasoline. Like many former vaudeville performers who turned to radio in the same decade, the stage-trained Wynn insisted on playing for a live studio audience, doing each program as an actual stage show, using visual bits to augment his written material, and in his case, wearing a colorful costume with a red fireman’s helmet. He usually bounced his gags off announcer/straight man Graham McNamee; Wynn’s customary opening, “Tonight, Graham, the show’s gonna be different,” became one of the most familiar tag-lines of its time; a sample joke: “Graham, my uncle just bought a new second-handed car… he calls it Baby! I don’t know, it won’t go anyplace without a rattle!”

The First 50 Years of Broadcasting

Going back to 1931, the names Farnsworth and Zworykin ring out as the editors of BROADCASTING MAGAZINE present a special 320 page, 1981 edition that takes in an amazing array of “firsts” in broadcasting!

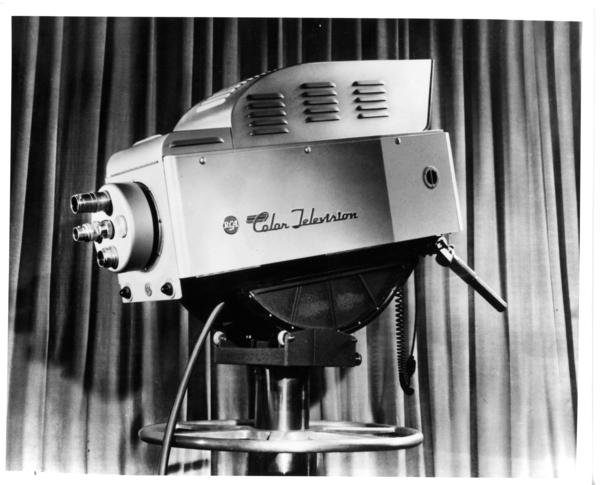

A PRIMER ON RCA’S EARLIEST COMPATABLE COLOR CAMERAS

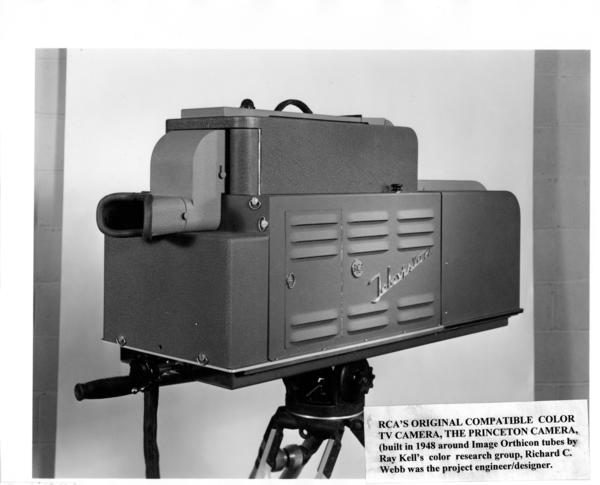

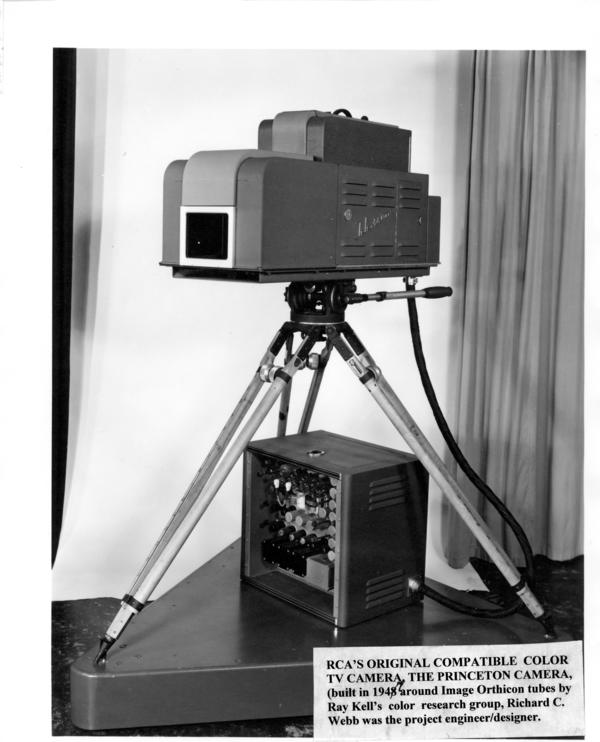

I’ve just recently been able see these stunning in-house marketing photos that reveal some news about the first three sets of RCA’s compatible color prototype cameras. We now know the “name” of the first set of color compatible prototype cameras.

These are the Princeton Cameras. There were two of these and after being built in Princeton NJ at RCA Labs, they were sent to NBC’s Wardman Park Hotel studios in Washington DC where they were put through their paces for the FCC, members of congress and of course the engineers in Princeton that saw everything on a closed circuit feed, while still developing support equipment. The other two camera types we’ll see here are the three Coffin Cameras and the four TK40 Prototype cameras.

If you look closely at the date in the photo label at the bottom right (top photo) notice that the photo is dated 1948, but the 8 is struck through to give us a date of 1947! Also, notice “additions” as we go and note that these first few images are most likely the first pictures as there are not any exhaust fans on top yet, AND…notice the big boxes that each camera is connected to. Chuck Pharis and I have come to the conclusion that these are what he calls an, “intermediate or auxiliary box”, which is just a place for components which were as of yet, unable to be included inside the camera head. As we go, you will see that at first there is a single cable from the camera to the box, but later these Princeton Cameras will have 3 cables to the box. The early DuMont cameras had these aux boxes too.

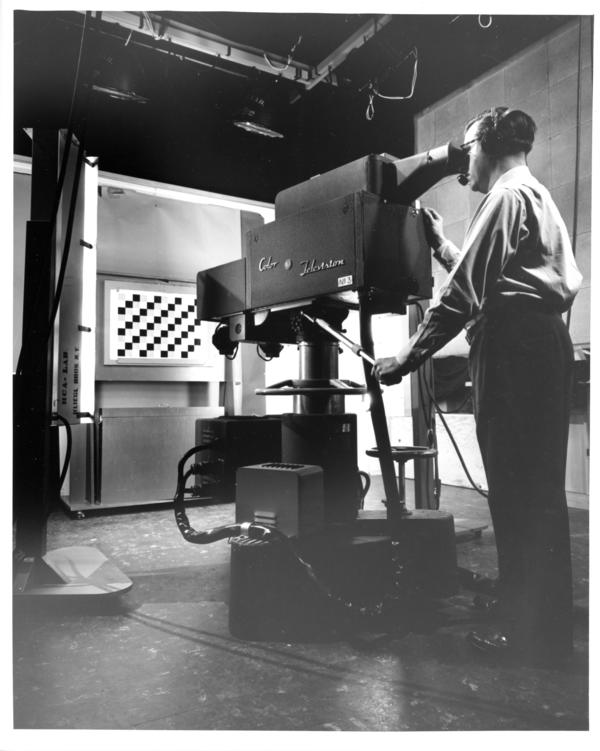

Below is Dr. Richard C Webb with his invention with the cowling off so we can see the optical system which uses what look like three 90mm lenses behind the dichroic mirrors. The preamps are on top, but notice the intermediate box underneath. You may have seen this image before, but this is the original uncropped image as you notice the crop marks for the smaller images.

The image below shows a bit of the inside with the rear door removed BUT, in the two images below, notice the cameraman seems to be gripping a rod (like a Zoomar rod) which now answers the question of just how focus was handled on this early model, which still depends on moving the camera in and out to achieve close ups as there is yet a zoom or turret lens system.

In the final two images (above) of the Princeton Cameras we see the final refinement that shows us a newly configured optical system box which is now in a separate enclosure with a cowl cover of it’s own. FYI, the smaller camera is the experimental Tri Color camera. Oh…and if you thought the viewfinder looked familiar, it is the same one RCA used for the TK10 and TK30 models.

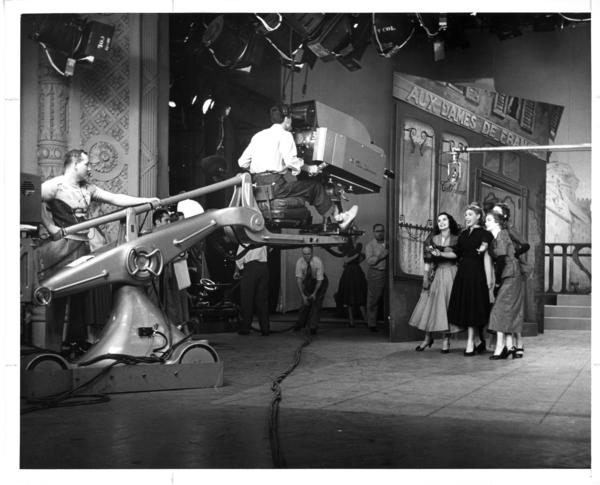

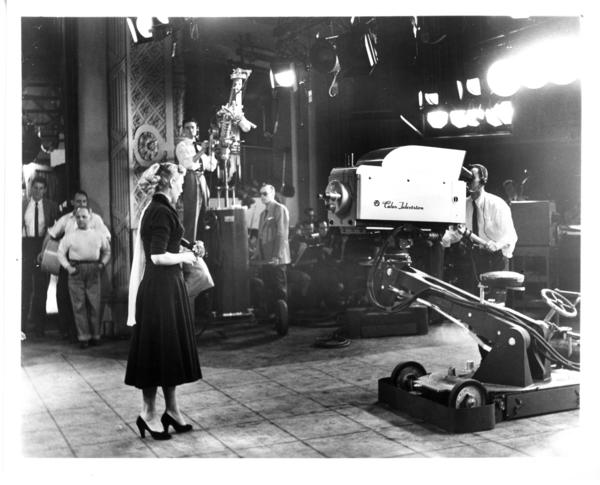

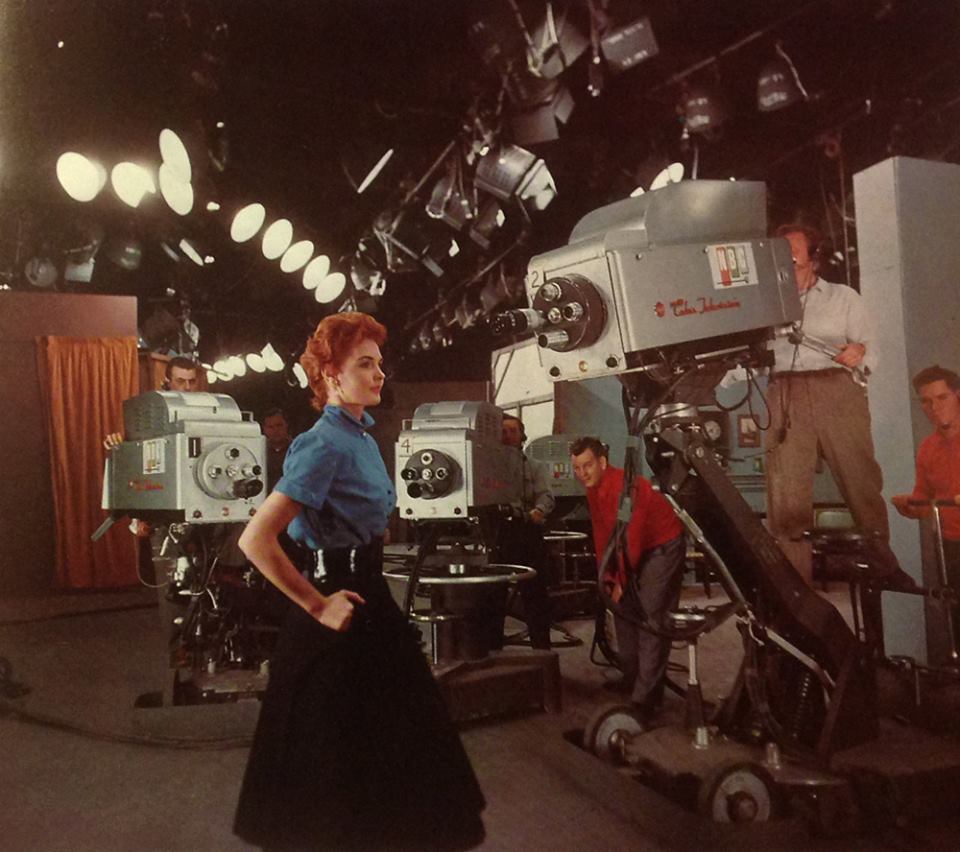

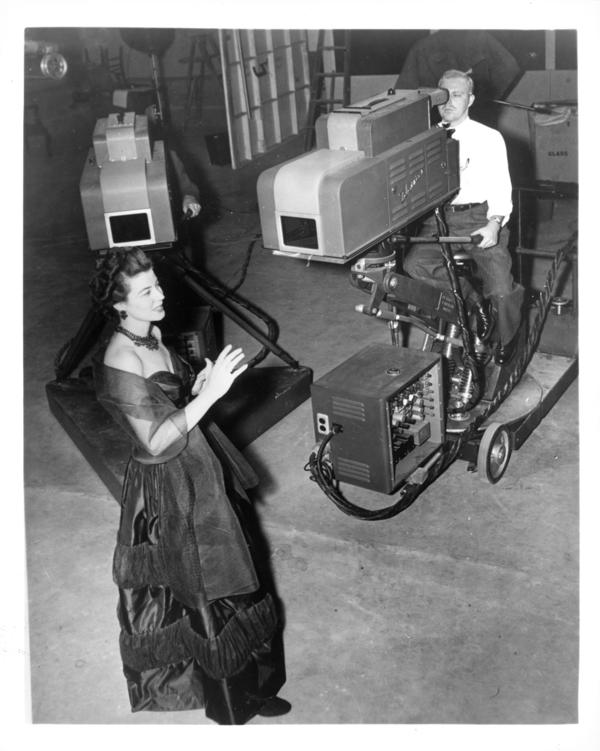

The Three RCA Coffin Cameras were the immediate successors to the Princeton Cameras and were also built in Princeton. When the Princeton Cameras were retired, they went back to RCA Labs there where they were bench tested a lot but compatible color trials had moved onward and “upward”…from NBC’s Wardman Park studio to Studio 3H at 30 Rockefeller Plaza. These black cameras were said to be big enough to be buried in so their nick name caught on…the Coffin Cameras.

Notice these cameras have the new turret mounted lenses and a side focus just like their black and white brothers, the TK10 and TK30. In the middle image is NBC Color Girl Marie McNamara in Studio 3H and at the bottom, is Nanette Fabre performing in the daily close circuit show that was shown to the engineers at 30 Rock, Princeton and in the RCA Exhibit Hall just across from NBC on 49th Street. These were in use for testing from about 1949 till 1952.

RCA TK40 PROTOTYPES

There were four of these cameras made and were used only at NBC’s first color studio at The Colonial Theater in New York which began testing in 1952. The hand of RCA’s top industrial designer John Vasos is evident in the now smooth lines of this classic look.

NBC’s 1938 vintage mobile units were retrofitted for color when Coffin Cameras were still in use and broadcast live from Palisades Park for one of the first color remote tests. One on the Colonial’s TK40 prototypes was also occasionally kidnapped for color field tests, and in 1954 when the Rose Parade was broadcast in color from Los Angeles, the new NBC Color Unit stopped by The Colonial to “borrow” all the cameras for a week.

The top two images show the TK40 prototypes with no vents on the viewfinder hood and that was the way ALL TK40s were made…all 28 of them, until the TK41 debuted in 1954. All except for one of the Colonial’s TK40s were retrofitted with vented VF covers as is seen in the final photo. Also, in that color image, notice the turrets on the two cameras on the right…those are salvaged from their Coffin Camera predecessors. I’ll bet the turret on Camera 3 (in the background) is glossy black too. -Bobby Ellerbee

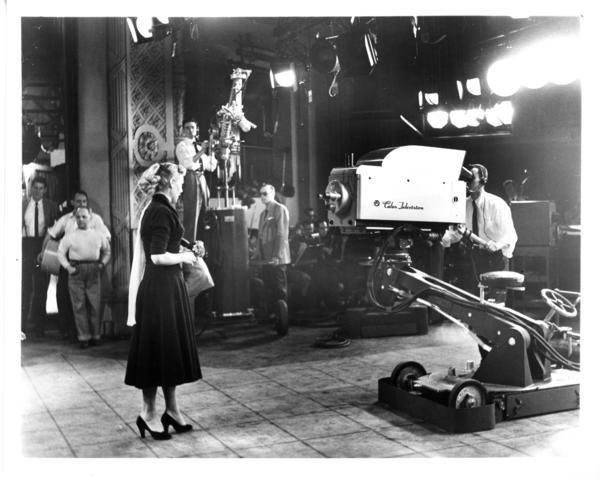

INSIDE NBC’S COLONIAL THEATER & RCA’S COLOR EFFORT

In all these 15 years of research, I have never found this whole black and white promotional film from RCA until just yesterday! This amazing film titled “Color Television; an NBC Documentary” shows some of the most advanced science of the day as we are taken behind the scenes not only at The Colonial Theater which was the very first color studio, but to RCA’s laboratories and factories in Princeton and Camden NJ and more.

There are many places to stop and ogle here, but I’ll point out a few highpoints for me, as they show us the prototype RCA TK40s AND the prototype of the first color camera (14:38) and the experimental Tri Color camera (19:11).

We get our first look inside The Colonial at 3:45 and our host is NBC’s Chairman, Pat Weaver. At 6:45 we see a novice actress who’s starred in NBC’s closed circuit color daily test broadcasts for two years, but by 1949 will have a TONY Award…Nanette Fabray!

At 8:40 we move to the Colonial control room with NBC Chief Engineer O.B. Hanson. No RCA promo would be complete without a few words from The General, and at the end (27:05) we get another look at the TK40 prototypes. This is just full of great, rare video of things and places we all often wondered about.

To help all of this flow better, I am including the 1953 RCA special promotional, color television magazine that covers a lot of what we see in the film that I think is also from 1953 or early ’54. By the way, notice the TK40s are mounted on the RCA friction heads that were made to hold the 90 pound TK30s of the day…not the 340 pound TK40. The good news is that Houston Fearless had just delivered to RCA their first cradle heads for the TK30s and were immediately put to work on the larger version for these great cameras. Thanks to Simon Crawshaw for the illusive video! Enjoy and share! -Bobby Ellerbee