- Home

- TV History

- Network Studios History

- Cameras

- Archives

- Viewseum

- About / Comments

Skip to content

Posts in Category: TV History

Page 110 of 136

« Previous

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

30

31

32

33

34

35

36

37

38

39

40

41

42

43

44

45

46

47

48

49

50

51

52

53

54

55

56

57

58

59

60

61

62

63

64

65

66

67

68

69

70

71

72

73

74

75

76

77

78

79

80

81

82

83

84

85

86

87

88

89

90

91

92

93

94

95

96

97

98

99

100

101

102

103

104

105

106

107

108

109

110

111

112

113

114

115

116

117

118

119

120

121

122

123

124

125

126

127

128

129

130

131

132

133

134

135

136

Next » The Original Amateur Hour With Ted Mack: Part 4

On July 16, 2013

- TV History

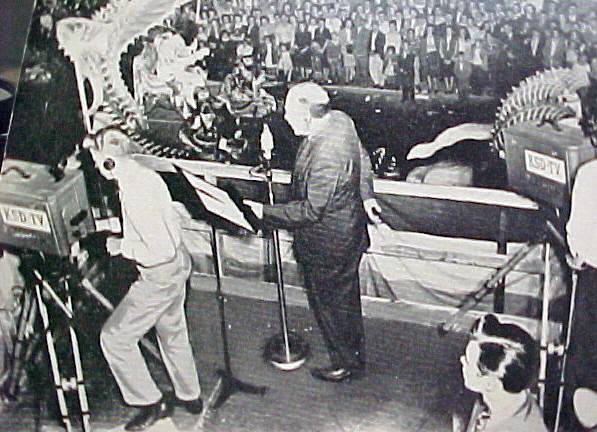

The Original Amateur Hour With Ted Mack: Part 4

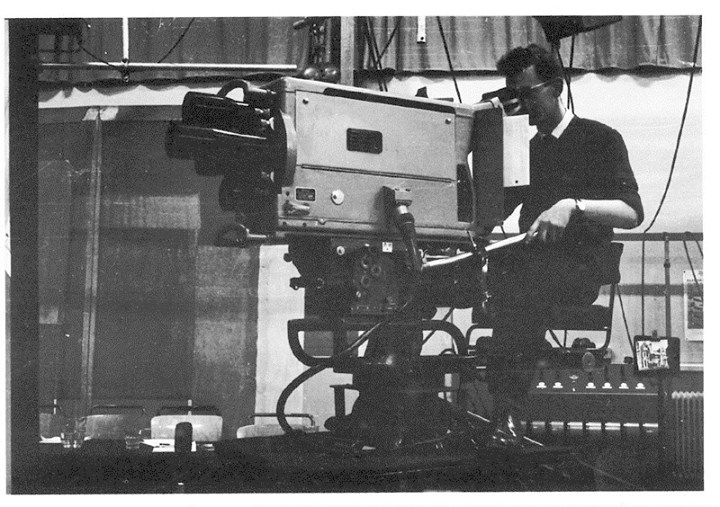

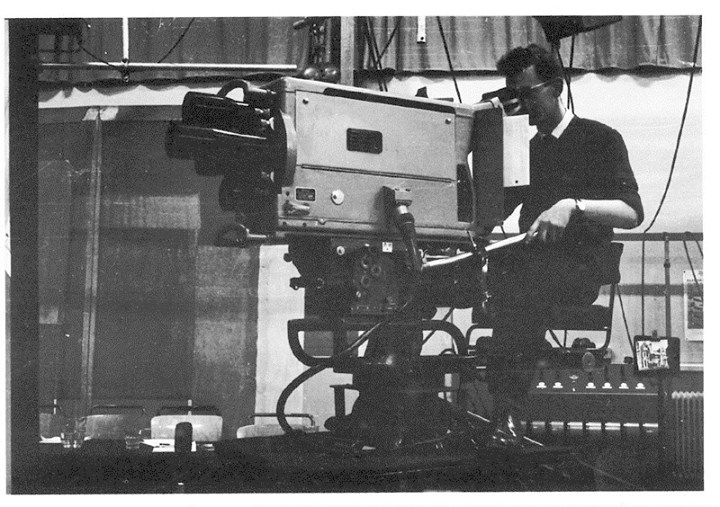

‘The Amature Hour’ originated from The Adelphi Theater in NYC which is most remembered as the place where the classic, 39 episodes of ‘The Honeymooners’ was shot using the Dumont Electronicams. The Adelphi was located at 152 West 54th Street in New York City, with 1,434 seats. It was owned by Dumont from around 1950 till 1957. In this photo of the show in progress, we see the two Dumont Iconoscope cameras that were used to shoot the show. Photo courtesy of Albert Fisher…the show’s producer.

Even From The Back, You Know Who This Is…

On July 15, 2013

- TV History

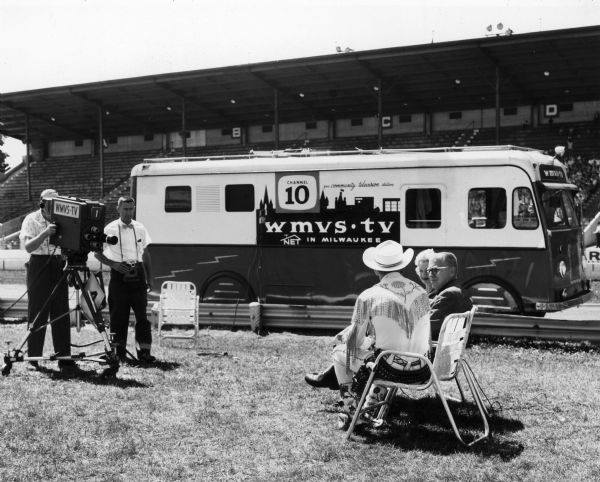

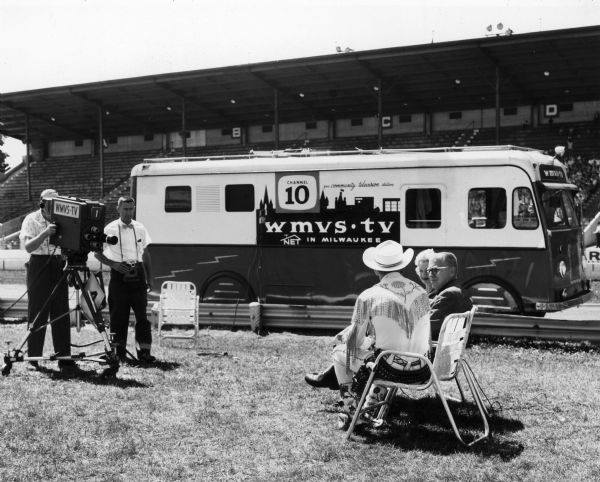

Even From The Back, You Know Who This Is…

If you grew up in the 50s, you’d know Roy Rogers from any angle! Here’s Roy and Dale doing an interview in Milwaukee, Wisconsin in 1961. I suspect they were there for an appearance at the state fair.

Ellerbee Camera Collection Video Tour

On July 14, 2013

- TV History

Ellerbee Camera Collection Video Tour

For those of you that have never seen this, here it is again. I shot this a couple of years back with a small 35mm photo camera and it shows all of the 16 cameras I have on display here in my home. At the time, I had about 25 cameras, now, with the addition of the 70+ ENG cameras, there are about 100 cameras in the collection. Enjoy!

Marconi Mark IVs and RCA TK60s In Action!

On July 14, 2013

- TV History

Marconi Mark IVs and RCA TK60s In Action!

From Jerry Lewis’s ‘The Patsy’ from 1964, this clip captures two great TV studio scenes. The first shows the Marconis in action and the second shows the TK60. Had the camera uses been reversed, it would have been correct as Sullivan never had TK60s, but did have Marconi Mark IVs. Since KTLA was owned by Paramount at the time, the Marconi cameras were theirs and that scene was probably shot there.

See Anything “Interesting” In This 1907 Photo?

On July 13, 2013

- TV History

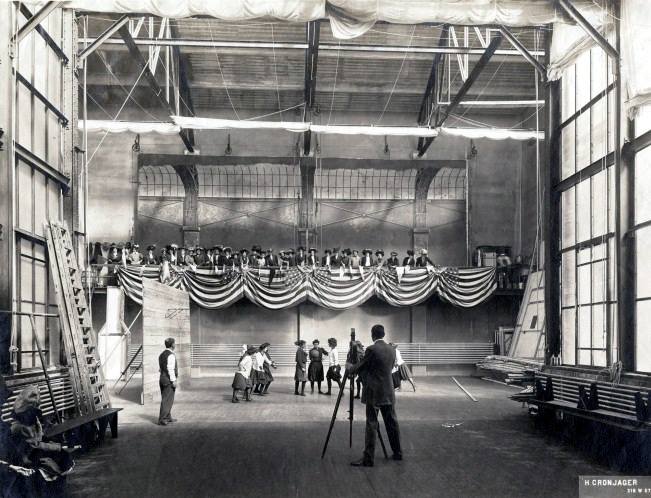

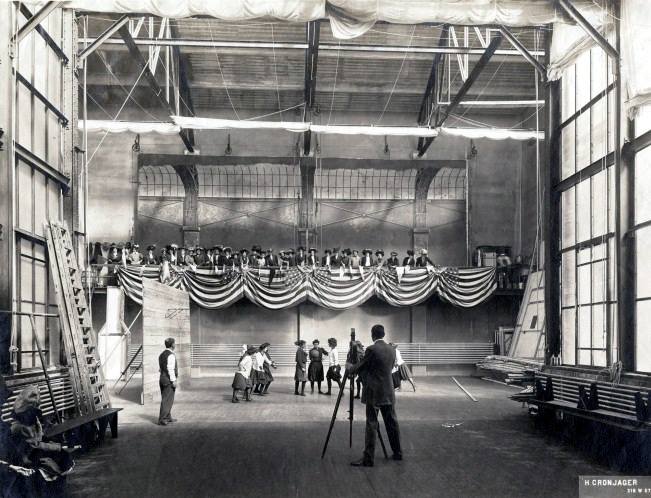

See Anything “Interesting” In This 1907 Photo?

Yes…a microphone! Believe it or not, Thomas Edison had been working on adding sound to film as early as 1895 with the Kinetophone. Basically it was a wax cylinder recording that was not synchronized with the images and debuted in the peep show style, single viewer, flip book consoles that predated the projection of film.

Experimentation with sound film technology, both for recording and playback, was virtually constant throughout the silent era, but the twin problems of accurate synchronization and sufficient amplification had been difficult to overcome. In 1926, Hollywood studio Warner Bros. introduced the “Vitaphone” system, producing short films of live entertainment acts and public figures and adding recorded sound effects and orchestral scores to some of its major features. During late 1927, Warners released The Jazz Singer, which was mostly silent but contained what is generally regarded as the first synchronized dialogue (and singing) in a feature film; but this process was actually accomplished first by Charles Taze Russell in 1914 with the lengthy film The Photo-Drama of Creation. This drama consisted of picture slides and moving pictures synchronized with phonograph records of talks and music. The early sound-on-disc processes such as Vitaphone were soon superseded by sound-on-film methods like Fox Movietone, DeForest Phonofilm, and RCA Photophone. The trend convinced the largely reluctant industrialists that “talking pictures”, or “talkies”, were the future. A lot of attempts were made before the success of the Jazz Singer,

The Edison Studios…Home Of The First Motion Pictures

On July 13, 2013

- TV History

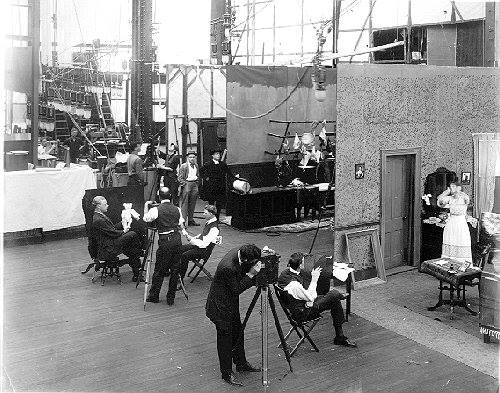

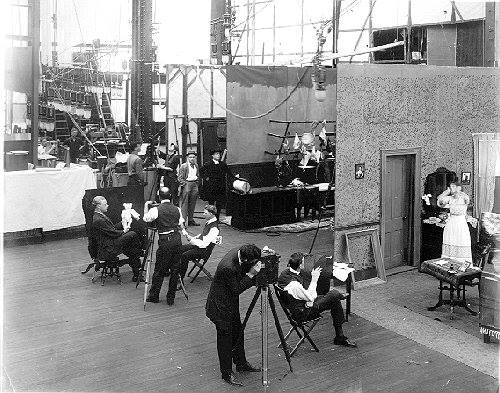

The Edison Studios…Home Of The First Motion Pictures

In 1907, Edison had new facilities built on Decatur Avenue and Oliver Place in the Bronx and the photo below was taken there in 1908. This was the third studio Edison built. Its first production facility, Edison’s Black Maria studios in West Orange, New Jersey, was built in the winter of 1892–93. The second facility, a glass-enclosed rooftop studio built at 41 East 21st Street in Manhattan’s entertainment district, opened in 1901.

Edison Studios was the original American motion picture production company owned by the Edison Company of inventor Thomas Edison. The studio made close to 1,200 films as the Edison Manufacturing Company (1894–1911) and Thomas A. Edison, Inc. (1911–1918) until the studio’s closing in 1918. Of that number, 54 were feature length, the remainder were shorts.

The first commercially exhibited motion pictures in the United States were from Edison, and premiered at a Kinetoscope parlor in New York City on April 14, 1894. The program consisted of ten short films, each less than a minute long, of athletes, dancers, and other performers. After competitors began exhibiting films on screens, Edison introduced its own Projecting Kinetoscope in late 1896.

The earliest productions were brief “actualities” showing everything from acrobats to parades to fire calls. But competition from French and British story films in the early 1900s rapidly changed the market. By 1904, 85% of Edison’s sales were from story films.

Some of the studio’s notable productions include The Kiss (1896), The Great Train Robbery (1903), Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland (1910), the first Frankenstein film in 1910, the first ever serial made in 1912 titled What Happened to Mary, and The Land Beyond the Sunset (1912). The company also produced a number of short “Kinetophone” sound films in 1913–1914 using a sophisticated acoustical recording system capable of picking up sound from 30 feet away. The studio also released a number of Raoul Barré cartoon films in 1915.

In December 1908, Edison led the formation of the Motion Picture Patents Company in an attempt to control the industry and shut out smaller producers.[2] The “Edison Trust,” as it was nicknamed, was made up of Edison, Biograph, Essanay Studios, Kalem Company, George Kleine Productions, Lubin Studios, Georges Méliès, Pathé, Selig Studios, and Vitagraph Studios, and dominated distribution through the General Film Company. The Motion Picture Patents Co. and the General Film Co. were found guilty of antitrust violation in October 1915, and were dissolved.

The breakup of the Trust by federal courts under monopoly laws, and the loss of European markets during World War I, hurt Edison financially. Edison sold its film business, including the Bronx studio, on March 30, 1918 to the Lincoln & Parker Film Company of Massachusetts.

First KFO…Two Points Of Interest

On July 12, 2013

- TV History

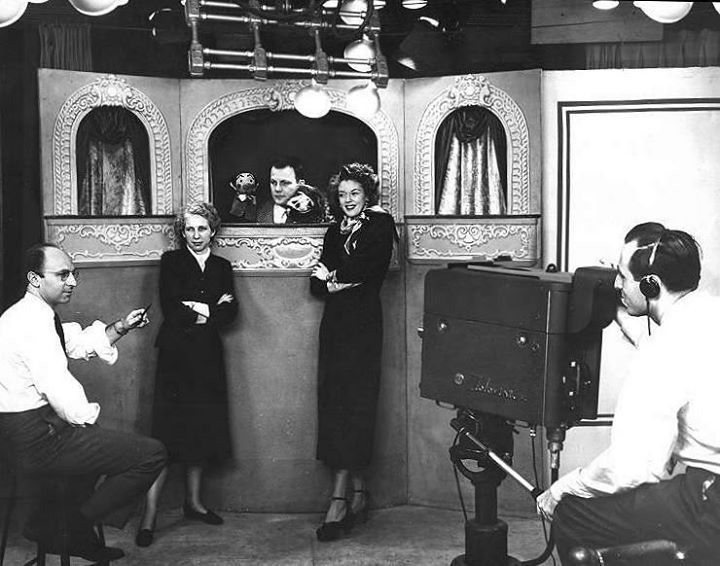

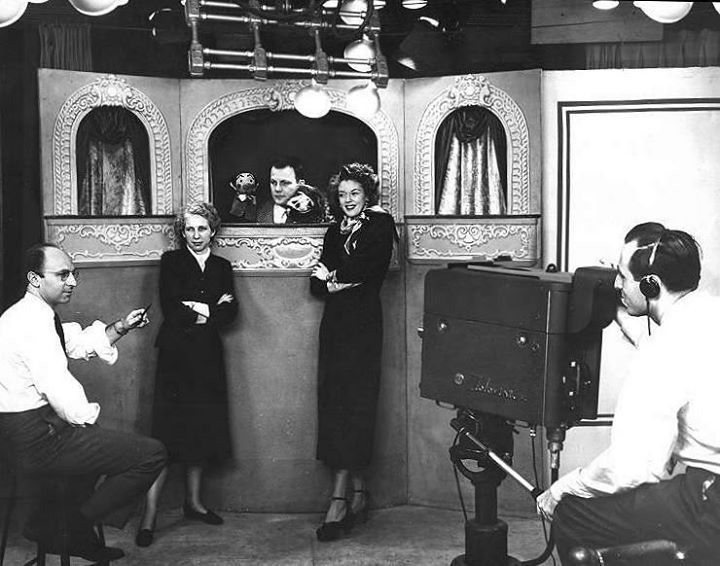

Two Points Of Interest…

Before it was renamed ‘Kukla, Fran And Ollie’ in October of 1948 when it moved to WNBQ and NBC, the show was called ‘Junior Jamboree’ and debuted on Chicago’s WBKB in November of ’47. Although WBKB was able to buy the new RCA TK30 IO cameras, it could not afford new pedestals and put the cameras on their two home made dollies that used a barber’s chair for the base. The dollies were built during WWII and had formerly supported Dumont Iconoscope cameras.

CBS Uses Thomson Cameras…1985 NCAA Championships

On July 11, 2013

- TV History

CBS Uses Thomson Cameras…1985 NCAA Championships

Yesterday, veteran cameraman Kevin Vahey mentioned in a note his surprise to see CBS using Thomson cameras on a remote in 1977 in Los Angeles. Kevin wondered if that was just an LA truck or if there was more to it. I think there was more to it and this video from 1985 is part of the reason. I think CBS did a lot of trials after the Norelco cameras began to age and the mobile units were good places to test new cameras. This video is was shot in Louisville Kentucky.

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Qf1F_YLtp4c

From CBS, the sports segment of a film for affiliates showing behind the scenes of the CBS Television Network. You see the heads of the divisions, talent and…

Vintage Video Collections

On July 11, 2013

- TV History

America’s Camera Collections

My friend Richard Wirth recently published this article “Vintage Video Collections” that shines a light on the custodians of what’s left of the vintage television equipment, and where it is now. Enjoy!

http://provideocoalition.com/pvcexclusive/story/the-collections

In 1953, color television became a reality in the US. At the time, the cameras weighed over 300 pounds and were referred to as “coffins” because they were so huge.

‘All Star Review’, 1952…One Of The First Camera Mounted Teleprompters

On July 9, 2013

- Archives, TV History

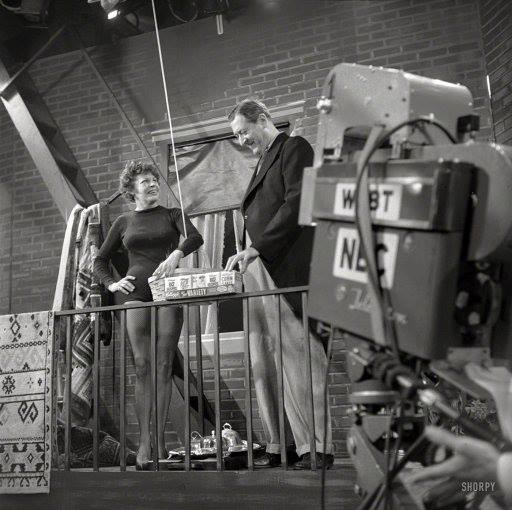

‘All Star Review’, 1952

In the last year of so of this NBC show, Martha Raye was the host of this popular show as it morphed from a rotating host format to a single host. Soon after, it became ‘The Martha Raye Show’. In this shot, Martha is rehearsing a spot for Kellogs with Arthur Treachur who played many a butler role and a few years later, went on to become Merv Griffin’s side kick and straight man. Notice the huge teleprompter being held onto the TK10 with a strap. Thanks to David Zornig and Jim Young for the photo.

Look Ma…No Viewfinders!

On July 8, 2013

- TV History

Look Ma…No Viewfinders!

The RCA TK30s became available in late 1946, but there was some element used in building the viewfinders that was in very short supply. The networks got viewfinders, but the local stations had to wait. The problem went away after about six months, but local stations that bought them had do make do for a while. Shown here is a 1946 Christmas parade in St. Louis, covered by KSD TV. The good news was that there were very few sets in use at the time. The only way to make this work was to put a monitor near the cameras and have the director talk the cameramen into the right shots.

Small World…As it turns out, this is one of my RCA TK60s.

On July 7, 2013

- TV History

Small World…

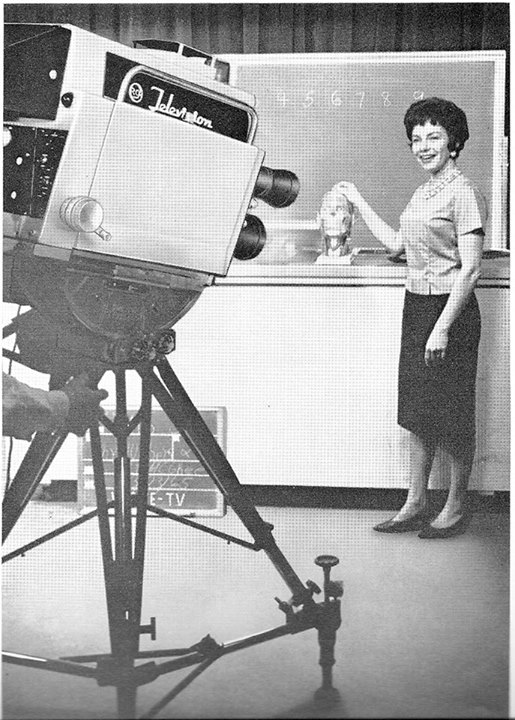

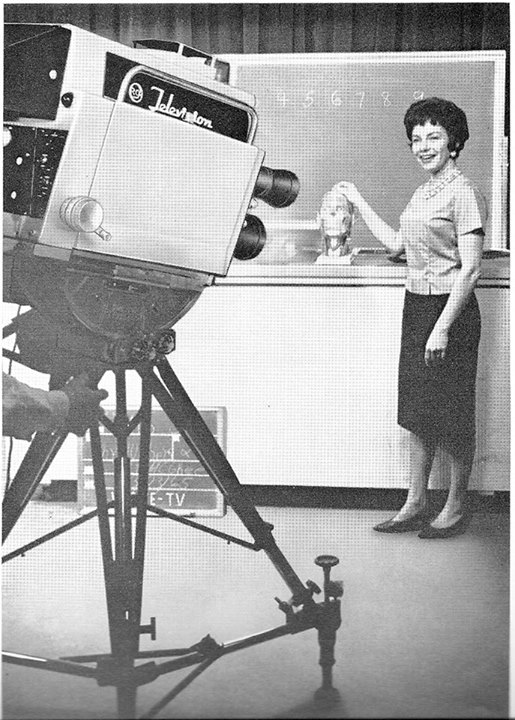

As it turns out, this is one of my RCA TK60s. I just found this photo in a 1960s RCA Broadcast News…it was shot at WCVE TV which is Richmond, Virginia’s PBS station. They had two TK60s and I have them both in my collection now.

One Of My Favorite Cameras…Marconi Mark IV

On July 6, 2013

- TV History

One Of My Favorite Cameras

This is the Marconi Mark IV. It’s standard tube was the 4.5″ Image Orthicon and this could have been the first camera to make use of the 4.5″ IO as the 1958 RCA TK14 used the 3″ and it was not till 1960 that the TK12 aka TK60 debuted with a 4.5″ IO. The camera debuted in 1958 and by 1960 had began to show up in the US. CBS used them at Television City and in Studio 50 (Ed Sullivan Theater) in New York. I think CBS also had some on network mobile units. WAGA and the PBS station in Atlanta had them and so did a big mobile production company based in Washington DC.

The Baughman Pedestal

On July 6, 2013

- TV History

The Baughman Pedestal

This little mobile pedestal was a real work horse from the 1950s till the 80s. Originally made by Baughman, Houston Fearless copied it as did other camera support makers including ITC. There was a hydraulic version and this one, the manual crank version for height adjustment. This is my RCA TK11/31 mounted on a manual crank Baughman pedestal. They were so strong, you could even mount TK42s on them which weighed almost 300 pounds.

The CBS Field Sequential Color System

On July 5, 2013

- TV History

The Answer to Randy West’s Question, And More…

In a recent post showing the CBS Field Sequential Color Cameras, Randy asked where the mechanical color wheel was on the camera. Take a look at the extra plate added just above the lens turret on this modified RCA TK10…the color wheel is mounted behind that plate. A red, blue, green and clear filter wheel spins between the “taking lens” (the top center lens) and IO tube, just inside the camera chassis. The small electric motor is mounted on the bottom rear of the camera (not shown).

Now, the more important part…a short Bio of the inventor of the CBS Field Sequential System…

Peter Carl Goldmark: Creator of LP records and Field Sequential Color

Below is CBS President Frank Stanton (r) and creator of the Field Sequential Color System, Peter Goldmark with one of the CBS field sequential studio cameras…a retro fitted RCA TK10.

Goldmark was born in Budapest, Hungary, in 1906. As a student at the University of Vienna he was fascinated by the technology of television. While pursuing his bachelor’s degree he designed a television receiver with a screen about the size of a postage stamp. After obtaining his Ph.D. in 1931, Goldmark decided to emigrate to the United States to join the Radio Corporation of America, ( RCA), then the premier laboratory for television research. He was refused a position with RCA, however, and took up with their competitors, the Columbia Broadcasting System ( CBS), for whom he accrued a long and impressive list of accomplishments.

In all, Goldmark received more than 180 patents for CBS. Though he labored for several years to develop more practical television technology, it was not until 1940 that he conceived of his first great idea. While attending a showing of Gone with the Wind (the first color film he had ever seen), he came upon an idea for color television. During the next three months he designed the system known now as field-sequential color.

Basically, the system used a standard black-and-white camera and television receiver; placed in front of the camera was a spinning disk holding three colored filters–red, blue, and green. By synchronizing the camera’s color disk with a second disk within the television, a very sharp color picture was achieved. The debut of field-sequential color broadcasts was delayed by the outbreak of World War II. After the war years, CBS petitioned the Federal Communications Commission (FCC) to approve Goldmark’s design.

At the same time, RCA was developing its own method for color television. The picture quality of the RCA system was vastly inferior to Goldmark’s; however, it was compatible with existing television sets–that is, a standard television could receive the RCA signal (albeit in black and white) but not the CBS transmission, for which a whole new television set was necessary. Since the Goldmark method would have made nine million black-and-white sets immediately obsolete, the FCC eventually ruled to make the RCA system the standard.

The field-sequential color television–which still provides the best color reproduction available–has found a niche, particularly in areas such as medical instruction that demand precise color definition. In the late 1960s, Goldmark modified his television to enable National Aeronautics and Space Administration ( NASA) to clearly photograph the surface of the Moon, even from the Lunar Orbiter’s altitude of 29 mi.(47 km).

Goldmark can also be considered the father of video recording. With the goal of producing a tool for educational media storage, he developed a system called electronic video recording (EVR). Basically, EVR consists of a cartridge wound with black-and-white film that could be slipped into a recorder/player machine. Even though it was filmed in black and white, Goldmark’s ingenious design used a separate recording track to store the color signal, so that the final playback would be in color.

One advantage of EVR over magnetic tape storage is that it can record still frames as well as motion; by filming a page of written information onto a single EVR frame, an entire encyclopedia can be stored on one cassette. Although video cassette recorders ( VCR ) have since captured the home recording market, the EVR is still considered useful in the storage of written material.

The idea for Goldmark’s most successful invention came to him one evening in the early 1940s. While listening to a recording of Brahms at a party, Goldmark was annoyed by the constant clicks and interruptions in the music, since the 78 rpm records were far too short to contain the entire concert, and the host had to periodically flip or change the disks. Goldmark envisioned an album whose grooves were cut much closer together and whose turntable turned much slower, allowing more music on each side. He worked on solving this problem for three years, ultimately producing the first LP record. His microgroove recordings held the equivalent of six 78 rpm records; also, by switching to vinyl, the LP’s recordings had a far superior sound quality. To combat the new CBS-manufactured LP, RCA quickly designed the 45 rpm “single.” Though the single record found some success, Goldmark’s LP absolutely conquered the market for more than forty years.

NBC Burbank Studio 1

On July 5, 2013

- TV History

Now You Know Why…

Ever wonder why Johnny Carson sometime looked like he was talking to a balcony audience? Well, take a good look at Studio 1 in Burbank and you’ll understand. Although there is no balcony, the audience seating is very high and at a pretty steep incline…like stadium seating and the people in the back are waaay up there. Thanks to Martin Perry for the photo.

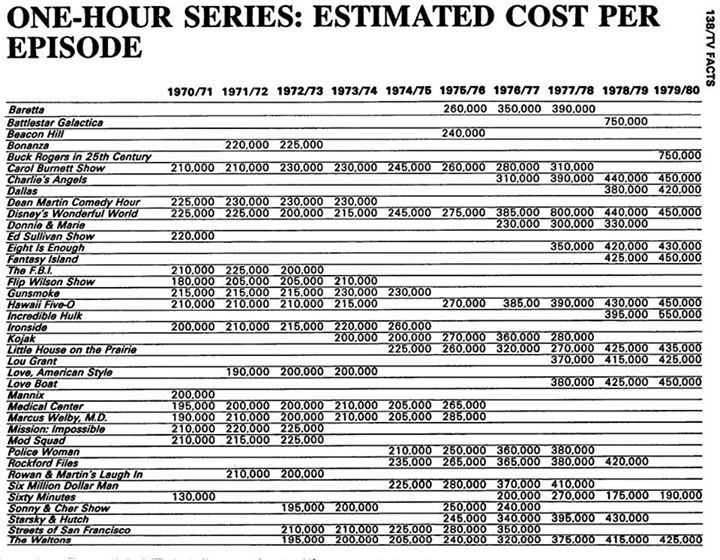

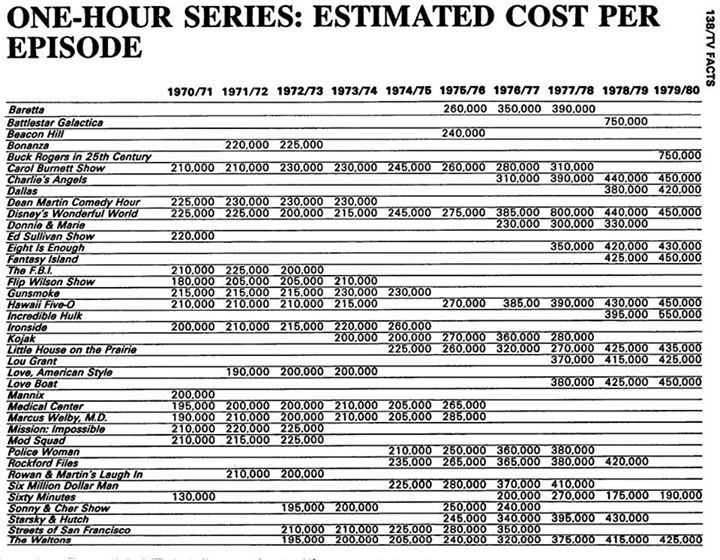

Per Episode Production Cost Of One Hour Shows 1970

On July 4, 2013

- TV History

Per Episode Production Cost Of One Hour Shows

The 1970s was the first full decade of all color programming for all networks. These figures are quite tame compared to today’s costs! Click to enlarge for the whole list.

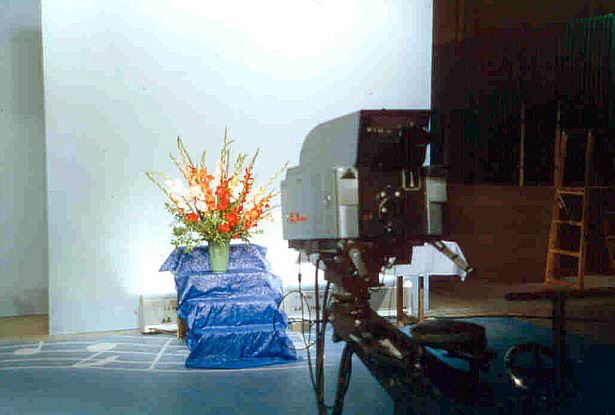

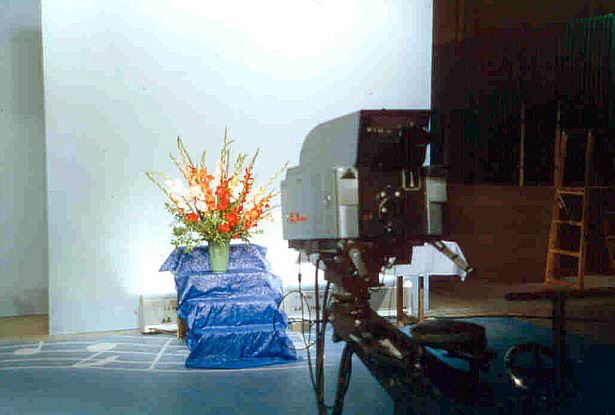

Early Color Challenges

On July 4, 2013

- TV History

Early Color Challenges

How do you develop first quality color broadcasts without the ability to properly monitor and calibrate your results? The answer for RCA was with patience and lots of testing. That’s what the Colonial Theater was for. This photo was taken there around 1953 and shows one (one of four) of the prototype models of the brand new RCA TK40 (notice no vents on the VF) shooting a flower arrangement because there were no color test charts yet. There weren’t even precision color monitors yet! Developing color broadcast systems at RCA presented a multitude of challenges.

How ‘I Love Lucy’ Was Produced…The Details

On July 2, 2013

- Archives, TV History

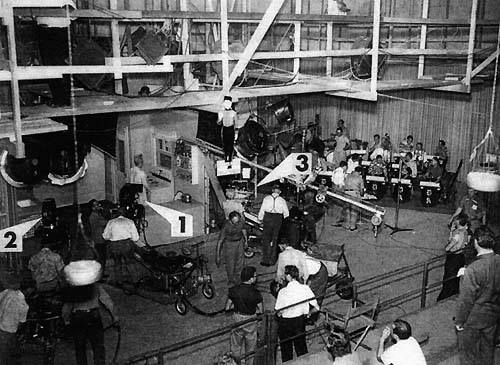

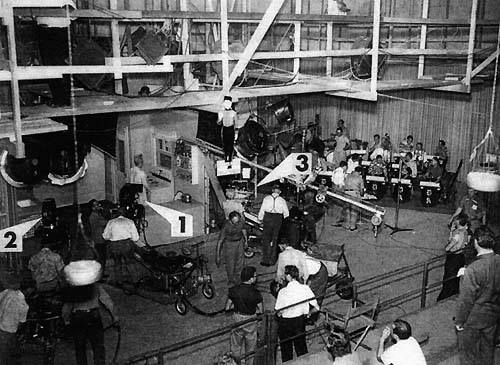

Above is a view of tri-set layout on Stage 2 of General Service Studio where the weekly “I Love Lucy” film show is produced. All lighting is from overhead, with units mounted so they can be changed with a minimum of time and effort. The show is photographed with three Mitchell 35mm BNC cameras, all shooting simultaneously. Camera (1) in center makes all the long shots, while closeups are filmed by cameras (2) and (3) at either side. Besides floor markers and memorized instructions, technical staff also is monitored by script girl via intercom phone system as show progresses. Retakes are rare and time between setups averages but a minute and a half.

Although each weekly show goes before the cameras at 8 o’clock Friday evenings, and is photographed entirely the same evening, the preceding four days are employed by the company in rehearsals, pre-production planning and script revision. the camera crews have but two schedules in the five-day period — on Thursday and Friday.

The director, actors and writers gather on the stage for a reading of the script on Monday and Tuesday; late Tuesday afternoon the first of the rehearsals are held. By Wednesday afternoon, the company is ready to run through the show for Director of Photography Karl Freund. This usually takes place at 4:30. No cameras are on the set at this time, nor are any members of the camera crews present. During this rehearsal, Freund studies the players and their movements about the sets, takes notes of how and where they enter and exit, and plans his camera operations and lighting accordingly.

The following morning at eight o’clock Freund and his electrical crew begin the task of lighting the sets, and endeavor to have the job completed by noon. At this time, the camera crew members come on the set and are briefed on camera movements, etc. With the crews and cameras assembled on the stage, camera action is rehearsed. This enables Freund to make any necessary changes in the lighting or operation of the camera dollies. Cues for the dimmer operator are worked out at this time. Chalk marks are placed on the floor indicating the positions the cameras are to take for the various shots or the range of the dolly action for a given scene.

At 4:30PM Thursday, there is another rehearsal — this time with the camera crews, gaffers, sound men, etc., on hand. Then at 7:30 the same evening a dress rehearsal is held, Freund, camera operators, gaffers and grips are on hand — but the cameras are not brought onto the floor. At this time the general plan of the show is discussed by the director. Notes are made for future guidance by all present. An open discussion then follows at which time lines of dialogue are cut, action shortened or deleted, camera movements analyzed…in short, everything is done at this time that will tighten up the show and improve its pace. This is the period in pre-production planning when problems are aired and suggestions made and considered.

On Friday, when the show is scheduled to be shot, there is a 1 PM call for everyone in the company — players, technicians, the producer and the director and his staff. If any major changes in the action, dialogue or camera treatment were decided in the previous evening’s discussions, these are now worked into the show during another general rehearsal.

A final dress rehearsal takes place at 4:30 PM, with the cameras now on the floor. Freund gives his lighting a final check, makes any necessary last minute changes before the company breaks for dinner.

After dinner, company and cast return to the stage, and there follows a general “talk through” of the show. At this time, further suggestions are considered and decisions made on any remaining problems, so that by 8 o’clock the company is ready to film the show.

In the meantime, the audience seating on the stage has rapidly filled and Desi Arnaz or some other member of the company is briefing the audience on the show, explaining the filming procedure, and emphasizing the importance its natural, spontaneous reaction plays in the show’s success.

Then for approximately sixty minutes the show is filmed. As soon as action is completed for one set up, the cameras, crew and players move rapidly to the next set up, and the action is resumed. All scenes are shot in chronological order. Each episode is 22 minutes long.

‘I Love Lucy’…What The Actors Saw

On July 2, 2013

- TV History

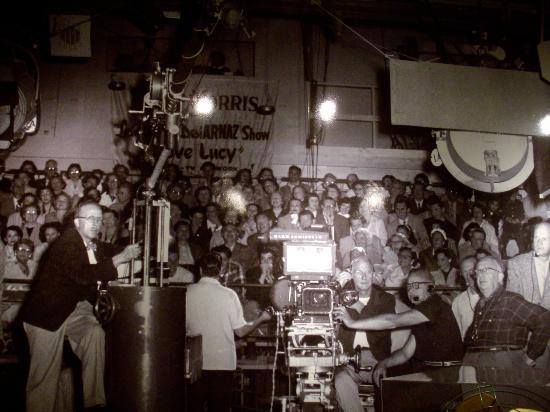

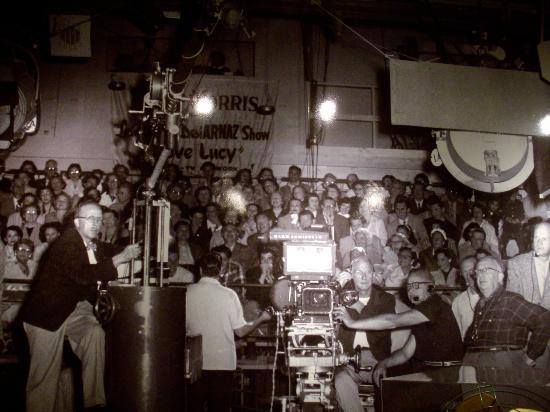

‘I Love Lucy’

From the set, here is a look at what Lucy, Rickey, Fred and Ethyl saw when they filmed. In the white shirt between the boom and camera, Desi Arnaz visits with the audience before he does the warm up, which he usually did for each show. The third man to the right of the camera in the dark shirt is Director of Photography Karl Freund.

Page 110 of 136

« Previous

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

30

31

32

33

34

35

36

37

38

39

40

41

42

43

44

45

46

47

48

49

50

51

52

53

54

55

56

57

58

59

60

61

62

63

64

65

66

67

68

69

70

71

72

73

74

75

76

77

78

79

80

81

82

83

84

85

86

87

88

89

90

91

92

93

94

95

96

97

98

99

100

101

102

103

104

105

106

107

108

109

110

111

112

113

114

115

116

117

118

119

120

121

122

123

124

125

126

127

128

129

130

131

132

133

134

135

136

Next »