- Home

- TV History

- Network Studios History

- Cameras

- Archives

- Viewseum

- About / Comments

Skip to content

Posts in Category: TV History

Page 118 of 136

« Previous

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

30

31

32

33

34

35

36

37

38

39

40

41

42

43

44

45

46

47

48

49

50

51

52

53

54

55

56

57

58

59

60

61

62

63

64

65

66

67

68

69

70

71

72

73

74

75

76

77

78

79

80

81

82

83

84

85

86

87

88

89

90

91

92

93

94

95

96

97

98

99

100

101

102

103

104

105

106

107

108

109

110

111

112

113

114

115

116

117

118

119

120

121

122

123

124

125

126

127

128

129

130

131

132

133

134

135

136

Next » Inside The 1939 World’s Fair Cameras

On March 6, 2013

- TV History

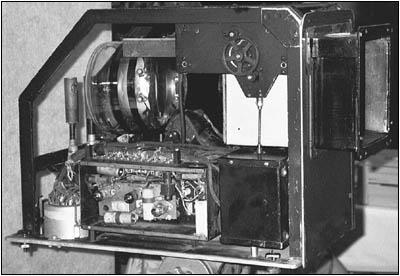

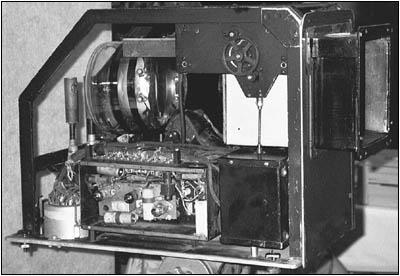

Inside The 1939 World’s Fair Camera

Here is what was inside one of the first RCA Iconoscope cameras. This was pretty much a point and shoot operation. The lens box was probably interchangeable to accommodate wide and medium angle lenses with a set focus. No viewfinder or eyepiece…just point it and hope for the best.

Eastmancolor: 1950

On March 5, 2013

- TV History

Eastmancolor: 1950

It’s hard to believe, but single strip 35mm color film was not available until 1950. This rendered Three-Strip color photography relatively obsolete, even though, for the first few years of Eastmancolor, Technicolor continued to offer Three-Strip origination combined with dye-transfer printing (150 titles produced in 1953, 100 titles produced in 1954 and 50 titles produced in 1955, the very last year for Three-Strip).

The first commercial feature film to use Eastmancolor was the documentary ‘Royal Journey’, released in December 1951. Hollywood studios waited until an improved version of Eastmancolor negative came out in 1952 before using it, perhaps most notably in This is Cinerama, which employed three separate and interlocked strips of Eastmancolor negative. ‘This Is Cinerama’ was initially printed on Eastmancolor positive, but its significant success eventually resulted in it being reprinted by Technicolor, using dye-transfer.

By 1953, and especially with the introduction of anamorphic wide screen CinemaScope, Eastmancolor became a marketing imperative as CinemaScope was incompatible with Technicolor’s Three-Strip camera and lenses. Indeed, Technicolor Corp became one of the best, if not the best, processor of Eastmancolor negative, especially for so-called “wide gauge” negatives (65mm, 8-perf 35mm, 6-perf 35mm), yet it far preferred its own 35mm dye-transfer printing process for Eastmancolor-originated films with a print run that exceeded 500 prints, not withstanding the significant “loss of register” that occurred in such prints that were expanded by CinemaScope’s 2X horizontal factor, and, to a lesser extent, with so-called “flat wide screen” (variously 1.66:1 or 1.85:1, but spherical and not anamorphic).

This nearly fatal flaw was not corrected until 1955 and caused numerous features initially printed by Technicolor to be scrapped and reprinted by DeLuxe. (These features are often billed as “Color by Technicolor-DeLuxe”.) Indeed, some Eastmancolor-originated films billed as “Color by Technicolor” were never actually printed using the dye-transfer process, due in part to the throughput limitations of Technicolor’s dye-transfer printing process, and competitor DeLuxe’s superior throughput.

Incredibly, DeLuxe once had a license to install a Technicolor-type dye-transfer printing line, but as the “loss of register” problems became apparent in Fox’s CinemaScope features that were printed by Technicolor, after Fox had become an all-CinemaScope producer, Fox-owned DeLuxe Labs abandoned its plans for dye-transfer printing and became, and remained, an all-Eastmancolor shop, as Technicolor itself later became.

Below, Alfred Hitchcock shooting ‘Rear Window’ in 1954 on Eastmancolor film stock.

CinemaScope

On March 5, 2013

- TV History

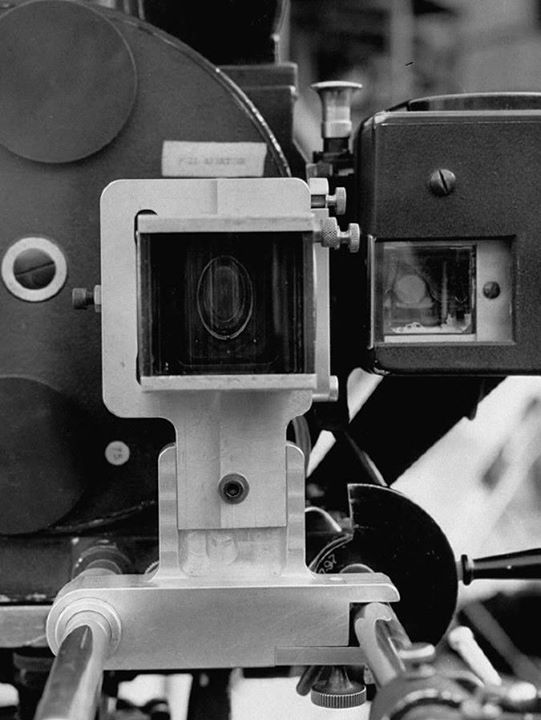

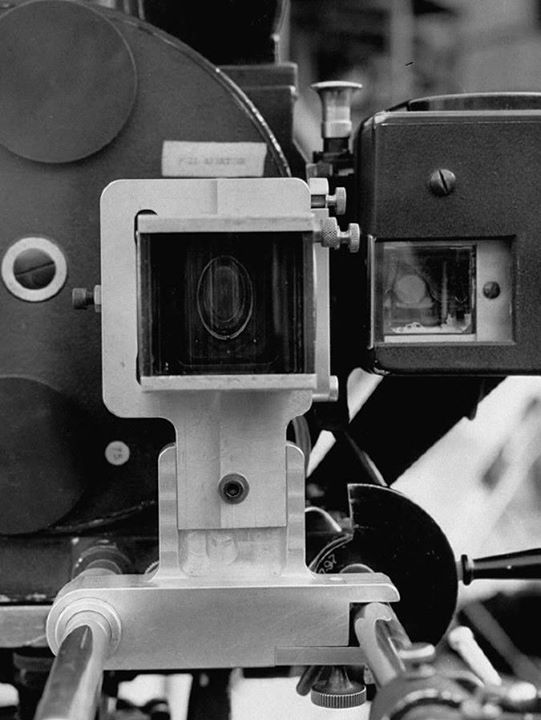

CinemaScope

If Cinerama was the star that guided the film industry into wide screen presentations, CinemaScope was the rudder that steered the course.

If you look closely at the photo below, you can see the essence of CinemaScope. See the long oval in the camera lens? That is the CinemaScope anamorphic lens used to photograph ‘The Robe’. It’s all in the lens…the anamorphic lens!

Ana means ‘re’ and morph means ‘shape’ so the lens reshapes the image. In the case of the motion picture, anamorphic lenses squeeze a wide image onto a narrow film frame. Projection through a similar anamorphic lens displays the image on the screen in its full, undistorted, width.

Anamorphic lenses are referred to by their compression (or expansion, in the case of projection optics) ratio. A 2:1 lens squeezes into the film frame an image 100% wider than a normal lens. A 1.5:1 squeezes in an image that is 50% wider, a 1.33:1 squeezes the image by 33%, etc. Most 35mm anamorphic films are made to be projected with 2:1 lenses.

For the indepth story and history of CinemaScope, I refer you once again to the brilliant work of Martin Hart and this 8 page discussion with tons of great photos!

http://www.widescreenmuseum.com/widescreen/wingcs1.htm

Technicolor

On March 5, 2013

- TV History

Technicolor

First, I must acknowledge The American Wide Screen Museum website by Martin Hart for most of this material. The site calls itself ‘the internet’s largest film technology resource’ and I can tell you that I have never seen anything that comes even close to capturing the exhaustive detail that Mr. Hart includes in all areas of film technology! There will be plenty of links as we go, but in this post, I am starting our discovery of the film processes with Technicolor.

Below is the famous Tri Color Technicolor film camera. In 1932 the first 3 strip camera was completed and it was expensive! It cost in excess of $30,000 during a time when the average American wage was less than $.50 per hour.

Most of us think that’s where Technicolor started, but much to my amazement, it started in 1915! If you think color television was complicated, wait till you read how the Technicolor process worked! Before the 3 strip camera in 1932, 1 and 2 strip cameras were used. Both shot chemically treated black and white negatives through a beam splitting prism with a red and blue-green filter, but print making is where it gets tricky. One side of strip A was dyed blue-green and one side of strip B was dyed red. Both strips were half the thickness of a regular print, until they were glued together.

I have not even scratched the surface on Technicolor, so I’m now directing you to Mr. Hart’s 10 page Technicolor spread on his fabulous site. Notice the page selection buttons near the bottom of each page. Enjoy!

http://www.widescreenmuseum.com/oldcolor/technicolor1.htm

This is the home page of the site if you would like to save it for later browsing.

http://www.widescreenmuseum.com//

For Junkies Only! Here is some glorious ‘junk’ at South Carolina’s PBS HQ

On March 3, 2013

- TV History

For Junkies Only!

Here is some glorious ‘junk’ at South Carolina’s PBS HQ. Enjoy!

I took these pictures about 5 years ago at a public TV facility. They say that, eventually, they are going to ‘do a museum’, so they are hanging on to some interesting old stuff. I still love looking at Chuck Pharis’s site to examine the truck loads of stuff he got in…spotting the jewels here and there in a load. Just thought you may like this too.

Back In Time…

On February 28, 2013

- TV History

Back In Time…

Here is a look back at how CBS covered the Orange Bowl game and parade back in 1960, starring the RCA TK30!

Behind the scenes of experimental colour transmission – January 1957

On February 28, 2013

- TV History

The Marconi BD 848 Color Camera, Rare Video

In a recent conversation with Chuck Pharis, I discovered that RCA had sold Marconi the rights to make their own version of the TK30 which became the Marconi Mark I. I suspect they also sold them the rights to make a TK41 as well, which became the BD 848. In this rare video, you can see the 848 in action at one of the first color transmission tests at the BBC, January 31, 1957. A lot of the chat is a bit dry, but the cameras appear several times throughout this short clip. Even the insides look exactly like the TK41. Enjoy!

In The Television Race, Others Were Ahead Of US…

On February 27, 2013

- TV History

In The Television Race, Others Were Ahead Of Us…

Do you know why the British worked so hard on electronic TV before WW II? In part, to push large scale manufacturing of cathode ray tubes and electronic components they could use in radar! They knew the war was coming and the more hi tech capacity, the better when the time came. This is a fascinating one hour documentary that lays out the progress of television’s development around the world and I think you will be as surprised as I was at how much progress others were making! Enjoy!

https://www.youtube.com/watch?NR=1&v=GQoeJbP6JH4&feature=endscreen

Episode 2 of the Granada Television documentary which looks at the early development and growth of the medium and the attempts to perfect television in the e…

RCA TCR-100 Videotape Cartridge System, Sales Reel

On February 27, 2013

- TV History

The RCA Tape Cartridge Recorder: TCR 100

First introduced at the NAB in 1969, the TCR 100 was a real breakthrough in tape handling and even received an Emmy. It could play tapes from :20 to 3:00 in length automatically which finally did away with having to juggle several reel to reel machines in each stop set.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=wM_2upiGUO0&ab_channel=AustralianTelevisionArchive

Tonight is Oscar Night! Here is how it’s done in the truck!

On February 24, 2013

- TV History

Tonight is Oscar Night!

A year of planning comes together into tonight’s three hour show, but here’s a look at the second by second work that goes on in the truck. This great clip from 2009 shows us how the pros do it!

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=0vLVbhuzWOk

I would have loved to see a PIP of the live production over the footage of the director calling the show just to see how close the cues were.

The Hollywood Palace

On February 24, 2013

- TV History

‘Hollywood Palace’: History

This is an excellent history of the show from TV.com. Enjoy!

The Hollywood Palace was an hour-long variety show that ran on the ABC-TV network from January 4, 1964 to February 7, 1970. Instead of a permanent host, guest hosts were used. Bing Crosby, a frequent guest host, hosted the first and last Hollywood Palace shows. Four of Bing’s Christmas specials, featuring his wife Kathryn and their 3 children, were actually Hollywood Palace shows.

The Hollywood Palace was a mid-season replacement for “The Jerry Lewis Show.” ABC originally had high hopes for Lewis’ live, two-hour variety series. They signed the comedian to a 5-year contract for a reported $35 million. The network also purchased the El Capitan Theater in Los Angeles and re-christened it “The Jerry Lewis Theater.” “The Jerry Lewis Show” premiered on September 21, 1963, but by Thanksgiving 1963 it was apparent that the show was a failure. ABC decided to replace it with a variety show. The network hired Nick Vanoff to produce the new show. Vanoff, in turn, hired William O. Harbach and Otto Harback to help him develop the series. They hurriedly came up with the concept of Hollywood Palace.

The final “Jerry Lewis Show” aired on December 21, 1963, and The Hollywood Palace premiered on January 4, 1964. (ABC aired a special on 12/28/63.) The Hollywood Palace took over the first hour of Lewis’ old time slot. The second hour was given to the local affiliates for their own local and syndicated programming. The old “El Capitan Theater” was once again re-named, this time as “The Hollywood Palace.”

The Hollywood Palace resembled a Vaudeville show. Raquel Welch, who was just a few years away from international stardom, was a regular on the 1964 shows. Welch appeared as the “billboard girl,” who changed the large cards that introduced the guests. The first 2 seasons of The Hollywood Palace were in black and white.

The Hollywood Palace switched to color at the start of its third season. The first color episode was broadcast on September 18, 1965. The “Hollywood Palace” theater became ABC’s first color videotape studio. It was also the home of “The Lawrence Welk Show,” which switched to color in the same month.

Collectors of this series may notice that black and white copies of the color episodes are available on VHS. These copies were mastered from B&W 16mm kinescopes. (Kinescopes were a videotape-to-film transfer produced by aiming a 16mm film camera at a TV monitor.) The original color videotapes do exist but they are not as accessible as the b/w kinescopes. These 16mm kinescopes were originally used by local U.S. stations and by the AFRTS. In the 1960’s, many local stations in smaller markets carried more than one network. And often it was the ABC programs that were bumped to other time slots. Instead of purchasing the then-expensive video tape recorders for time-shifting purposes, the stations opted to use 16mm kinescopes provided by the network. Kinescopes were also used by the AFRTS which operates TV stations on overseas military bases. The AFRTS prints usually do not have the original network commercials.

The Hollywood Palace Broadcast days/times Seasons 1 through 4 – Saturdays 9:30pm Eastern Season 5 (1967-68) Tuesdays 10:00pm Eastern (through 2-Jan-68) Season 5 – Saturdays 9:30pm Eastern (13-Jan-68 through end of season) Seasons 6 & 7 – Saturdays 9:30pm Eastern.

‘Hollywood Palace’: The Final Show, Full Episode Hosted by Bing Crosby

On February 24, 2013

- TV History

‘Hollywood Palace’: The Final Show, Full Episode

Hosted by Bing Crosby, this is a star packed hour of highlights from their seven year run on ABC. FYI, the first two seasons were done in black and white, with RCA TK60s. The show switched to color at the start of its third season. The first color episode was broadcast on September 18, 1965. The “Hollywood Palace” theater became ABC’s first color videotape studio. It was also the home of “The Lawrence Welk Show,” which switched to color in the same month.

You name the star, they are here! Sammy Davis, Jimmy Durante, Judy Garland, out takes, music, variety and animal acts, Joan Crawford, a Gloria Swanson – Buster Keaton skit, Martha Ray, Charlie McCarthy, Tim Conway, Phyllis Diller, 2 Milton Burl’s, Groucho Marks, Jack Benny, George Burns, Don Knots, Dean Martin, Perry Como, Betty Davis and more. Here is a link to the episode guide. Enjoy!

http://www.tv.com/shows/the-hollywood-palace/episodes/

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=8llfDmnX1ss

Popular, long-running Saturday night variety show of the mid-to-late 1960’s, originating from the Hollywood Palace Theater (formerly the El Capitan) on Holly…

Ikegami: History and Chronology

On February 21, 2013

- TV History

Ikegami: History and Chronology

The Los Angeles Olympics, one of the proudest moments in American history, was just one way in which Ikegami showcased its achievements, because it was Ikegami’s advanced broadcast cameras and monitors used extensively by ABC that played a critical role in bringing this international athletic event to television viewers the world over. Performance, brilliant color, and absolute reliability once again established Ikegami’s undisputed leadership in broadcast equipment engineering and design.

In 1964, the seeds of this organization were planted in a small sales office in New York City. Soon, Ikegami quickly outgrew its Manhattan headquarters. The company’s expansion ultimately required three relocations before its arrival at the present custom-built, 90,000 square-foot complex in Maywood, New Jersey, in 1978. Today, Ikegami’s longstanding history as a pioneer in broadcast technology remains unsurpassed, distinguished by such introductions as the first practical portable color TV camera and the first all-electronic, computer-controlled studio camera.

The story of Ikegami Electronics (U.S.A.), Inc., however, is but a single chapter in the legacy of its parent company, Ikegami Tsushinki Ltd. Founded by Kosei Saito in the Ikegami district of Tokyo, the company began manufacturing telephone coils in 1946. Three years later, with the advent of the television industry in Japan, it introduced studio and measuring equipment for both TV and radio. Its early broadcast designs were developed in cooperation with the renowned Technical Research Laboratory of NHK (the Japan Broadcast Corporation). Soon afterward, Ikegami became the first company in Japan to use transistors in broadcast equipment. It was already well on its way to pioneering the age of Electronics News Gathering (ENG) with the development of its first portable hand-held TV camera. This portable TV camera made its worldwide debut in the United States in May 1962, when CBS used the product to document the historic launching of the first manned space flight of Mercury 7, The demand for high quality, lightweight and reliable field cameras grew tremendously from this start, revolutionizing broadcast and video production in the process. Ten years later, Ikegami made yet another breakthrough by introducing its first color hand-held camera -the HL-33 – for broadcast use.

Ikegami continues to reap honors for its research and development in video technology. It is the recipient of two Emmy Awards for Outstanding Achievement in the Science of Television Engineering: for the development of digital techniques in automatic studio camera set up and for the design of the EC-35 Electronic Cinematography Camera. Ikegami technology has claimed many “firsts” throughout its corporate history. But for a select group of people who came to the United States from Japan in 1964 and for those who have since joined the company, the Olympic Games in Los Angeles signaled a special moment -the culmination of years of dedication and hard work. Ikegami cameras were recognized by the broadcast profession as “the best”. And the story has grown even greater since then.

Company Chronology:

1960’s

Established under the name of Ikegami Electronics Industries Inc. of New York on December 28th, 1964

Ikegami cameras used to broadcast the excitement of the Mexico Olympics.

1970’s

First display monitors delivered to Incoterm Corporation (Honeywell Information Division).

Ikegami studio and field cameras used at Winter Olympics in Sapporo, Japan.

Introduced the TK-355, the Ikegami’s first one-inch tube format color studio camera.

Developed the HL-33 “Handy LookyEhand-held color broadcast camera. The first camera in the world to use one-inch Plumbicon tubes. First delivery in the U.S.A. made to CBS, signaling the birth of the ENG (Electronic News Gathering) age.

Unveiled the HK-312, the first all electronic computer-controlled color studio camera in the world, at the SMPTE Show in New York.

First HL-33 hand-held cameras in South America delivered to TV Globo in Brazil.

American Broadcasting Company (ABC) selected Ikegami’s innovative HK-312; first delivery in the U.S.A. made to KABC.

Introduced the HL-35, the world’s first ENG color camera using 2/3-inch Plumbicon”‘ tubes.

Changed its corporate name to the current Ikegami Electronics (U.S.A.), Inc.

First HK-312 computer-controlled studio cameras in South America delivered to TV Globo in Brazil.

Introduced the HL- 77 ENG/EFP handheld camera at NAB.

Introduced the HK-357 at National Association of Broadcasters convention.

Introduced the HL- 79A ENG/EFP color camera at the SMPTE Show.

1980’s

Introduced the ITC-350 low cost hand-held color camera.

Received the Engineering Achievement Emmy. Award for the development of digital techniques for automatic set up of TV cameras.

Delivered its 100,000th display monitor to Honeywell Information Systems in the United States.

Introduced the HK-322 fully automated studio color camera.

Introduced the ITC- 730 low cost hand-held camera.

Began shipments of color display monitors.

Received an Emmy Award for the EC-35 Electronic Cinematography camera.

Introduced the first High Definition TV camera system in the USA.

Delivered the first HK-322 studio cameras to KOMO-TV.

Introduced the HL-95 Unicam, the most versatile one-piece hand-held camera; first six units delivered to ABC for use at the Los Angeles Olympics.

Hundreds of Ikegami cameras and monitors used by ABC for coverage of the Winter Olympics in Sarajevo and the Summer Olympics in Los Angeles, California.

Celebrated the unprecedented sale of the 5000th HL-79 series ENG/EFP camera.

Introduced HK-323 1″ and 2/3 “field/studio cameras.

Introduced HK-355 2/3″ CCD field/studio cameras.

Introduced HL-55 2/3” CCD hand-held cameras.

(Plumbicon is Registered Trade Mark of N.V.PHILIPS)

1990’s

Emmy for Skin Detail, first applied to a broadcast camera in the HK-327

HK-377, top-of-the-line high resolution CCD studio camera, sales to ABC and CBS for network production

Introduction of the broadcast industries first tapeless camcorder, the DNS-11

Development of the HK-388, full digital studio camera

Introduction of the HDK-790, the industries first full digital HD camera system

Development of Chip C4 video processing ASIC with 0.18 micron design, equivalent to 3.3 million gates

2000’s

Introduction of the industries first HD triax system

Introduction of the first HD wireless RF camera system, the HDL-0101

Introduction of CMOS sensor technology for broadcast cameras, HDL-40C & HDK-79EC

Ikegami’s HDK-79NA provides first HD Aerial coverage from the Goodyear Blimp at the US Open, Monday Night Football and the Super Bowl (Jan.2005)

If Walls Could Talk…

On February 21, 2013

- TV History

If Walls Could Talk…

This is the hallway at NBC Burbank that Johnny Carson walked for his 20 years there. The hallway separates Studio 1 and Studio 3, with 1 being on the left. These days ‘Access Hollywood’ shoots in Studio 1 and I think ‘Days Of Our Lives’ shoots is 3. Thanks to David Crosthwait for the photo.

Ralph Levy: Director Extraordinaire

On February 20, 2013

- TV History

Ralph Levy: Director Extraordinaire

Ralph Levy, TV pioneer and two-time Emmy winning director, is remembered by TV historians as the man who directed the original ‘I Love Lucy’ pilot in March, 1951 — which made his passing on the date of Lucy’s 50th Anniversary all the more poignant.

Born into a family of Philadelphia lawyers, Ralph was stage-struck from an early age. Bowing to family pressures, he earned a degree from Yale University, from which he was graduated just in time to serve in the Army during World War II.

Television was then in its embryonic development stage in New York City, and Levy landed a job of assistant director at CBS. Early assignments included covering sporting events such as boxing, basketball and professional football games. If nothing else, the apprenticeship allowed him to learn all about the cameras, lenses, lights and other new video technology. Ralph was never shy about his interest in musical comedy, and within a few months CBS gave him a chance to switch from sports to entertainment. They assigned him to work on the television edition of ‘Winner Take All’, a question-and-answer quiz program that had proven very popular on CBS Radio.

In early May of 1949, Ralph was asked to direct a variety show called The 54th Street Revue. Ralph managed to get the first of the shows on the air in only 4 days — an accomplishment that earned him both management’s attention and a reputation for working swiftly and efficiently.

That fall, CBS asked Levy to move to Los Angeles to direct a new variety series starring famed radio comedian Ed Wynn. If network TV in New York was just beginning, in Los Angeles it was virtually non-existent…

The Ed Wynn Show, Levy soon discovered, would be the first major network show on CBS to originate from Hollywood. It would be shown “live” on the West Coast every Thursday night at 9PM. A kinescope recording of the show would be made, sent to New York, and played for East Coast and Midwestern stations two weeks later. Such delays were necessary because the transcontinental cable was not yet in place that would allow for national live telecasts to originate on the West Coast.

The Ed Wynn Show premiered on October 6, 1949, and almost immediately ran into a talent booking problem. Big-name movie performers wanted nothing to do with the new video medium. Wynn started booking talent from the recording industry (Dinah Shore), old friends (Buster Keaton) and stars from network radio. In late December, Ed’s guests were Lucille Ball and Desi Arnaz.

“This was one of the first times I ever did anything on TV,” Lucy recalled later. “So frightening, but so wonderful. I’d never been in such a hurried, chaotic setting with these monstrous television cameras all over the stage and not enough rehearsal. But it was great fun.”

The script that night went out of its way to spotlight 32-year-old Desi, who appeared with Wynn and Ball in a comedy sketch, and even afforded him the opportunity to sing “Babalu.”

A few weeks later, CBS asked Lucy to consider transferring her radio series, ‘My Favorite Husband’, to TV. They wanted her — but did not know how her Latin husband would fit in.

Levy, meanwhile, had come to be the network’s fair-haired boy in Hollywood… In April, he expanded his duties to include directing the new Alan Young Show, a weekly half-hour comedy-variety skein starring the young Canadian who today is more remembered for his role ten years later in the sitcom Mr. Ed.

One of the most successful programs on CBS Radio that season was ‘You Bet Your Life’, starring the irrepressible Groucho Marx. The show’s sponsor, DeSoto-Plymouth Automobiles, was interested in adding a TV version — and both CBS and NBC wanted to carry it. Groucho later recalled, “You Bet Your Life shot up to Number 6 in the ratings. When both major networks — NBC and CBS — approached us about going on television, a bidding war started. Since we were already at CBS, it seemed likely we’d stay there. One of their star directors, Ralph Levy, helped us with the pilot show. When the dust settled, NBC was the high bidder. Levy stayed at CBS…”

The Ed Wynn Show ended its nine-month run on July 4, 1950, and Ralph headed to Mexico for a much-needed vacation. He had hardly unpacked when an emergency call came from Harry Ackerman, head of CBS’ Hollywood operations. “He asked me to come back the next day,” Ralph remembered later. “George Burns and Gracie Allen had agreed to go on television, and Harry wanted me at the first production meeting.” So much for Levy’s vacation…

A pilot was prepared and quickly sold to Carnation Milk Company, and ‘The George Burns – Gracie Allen Show’ was scheduled for a fall premiere. George was afraid to take on a weekly show all at once, particularly one that was to be done “live,” so CBS agreed to air it on an alternate-week basis. Complicating matters, especially for Ralph, was the fact that the network wanted to do the first 6 shows from New York. (The show could get better media coverage there, the network reasoned.) The cast and crew were sent to New York, and Ralph became bi-coastal for three months.

Making his life even more interesting was the fact that George Burns’ best friend, Jack Benny, was toying with the idea of getting into television himself. Naturally, he wanted Ralph to direct. But Benny was even more shy about TV than George and Gracie, and agreed to do only four half-hour specials that first 1950-51 season.

Lucy and Desi Arnaz, meanwhile, spent the summer of 1950 performing a comedy act in vaudeville theatres across the country, and by late fall had convinced CBS to let them try a new TV series together. Lucy’s radio writers — Jess Oppenheimer, Bob Carroll Jr., and Madelyn Pugh — went to work to create the format. Ralph Levy was asked to direct.

“I was anxious to direct Lucy’s pilot because I had worked with her on The Ed Wynn Show,” Levy recalled later. “I remember that the script called for Lucy to parade around the living room with a lamp shade on her head — trying to prove to Desi she could be a Ziegfeld Girl. I didn’t think she was walking the right way, so I showed her how it should be done — not knowing that she had been a showgirl for many years. Instead of telling me off, she simply played along with me. She was so professional and so good. She walked away with the whole show.”

The pilot was filmed on Friday evening, March 2, 1951 (Desi’s 34th birthday) in Studio A of CBS’ Columbia Square headquarters in Hollywood. It was the same stage used for the Wynn Show a year earlier. “There were only two sets,” Lucy recalled. “One was a living room and the other the nightclub where Desi worked. The show was shot live with a studio audience in attendance, as most TV shows were being done then. There was no tape yet. The images were recorded on film from a TV screen, providing us with the required kinescope.”

By the end of April the Lucy series, now titled ‘I Love Lucy’ had sold to CBS and Philip Morris — neither of which wanted the actual series to be done like the pilot (and the Wynn Show) via kinescope. The Arnazes balked at moving to the East to do the show live out of New York, so plans were set in motion to have the show filmed in Los Angeles using 35mm film. Levy, CBS’s first choice to direct, begged off: he knew he already had his hands full directing the Alan Young and Burns ‘n’ Allen series (plus the Jack Benny specials!). Levy also did several, live CBS ‘Playhouse 90’ presentations when his schedule allowed.

Interestingly, a year later, after ‘I Love Lucy’ proved a quality series could be done on film, Burns and Allen decided to do their shows on film, too (rather than “live”). Their company, McCadden Productions, moved onto the General Service Studio lot and became neighbors to Desilu and ‘I Love Lucy’. In 1953, Ralph retired from Burns ‘n’ Allen, and with The Alan Young Show ceasing production, he concentrated his energies on the now bi-weekly Jack Benny Program. He remained at Benny’s side another four seasons, then returned in 1959 to helm two hour long Benny specials. For these shows, he won his first Emmy Award.

Ralph won a second Emmy two years later for first Bob Newhart Show, a weekly half-hour of stand-up comedy and variety.

When filmed sitcoms became the order of the day, Levy adapted: he directed the pilots of ‘The Beverly Hillbillies’ and ‘Green Acres’, and two seasons of ‘Petticoat Junction’, all for his friend Paul Henning, one of George Burns’ writers who had since become a successful producer. (Petticoat, reunited him with actress Bea Benederet, who had been a regular on the Burns show.) Ralph later attempted to do dramas, programs like ‘Hawaii Five-O’, and feature films, but somehow, his heart was not in these projects: he missed the live audiences that early television and the theater had provided. The thrill of “opening night” was missing.

Levy spent several years in England in the 1970s, working for BBC Television, and taught TV production classes at Cal State Northridge and Loyola Marymount University.

Reflecting back on the various stellar performers with which he had worked, Ralph once observed, Groucho really was grouchy, probably because he “suffered from an inferiority complex.” Wynn was cerebral; Allen was always prepared, funny and “a doll” to work with. Ball was a top-notch clown, hard worker and tough business-woman. Benny, he always said, was the best of all, “a marvelous man.”

As for the new breed of television comedies, he found many of the shows to be too loud and vulgar for his taste. Working on modern shows “was not the same as working with Ed Wynn, or George and Gracie, or Jack. These people were from another era of show business; one in which you took literally years to build your comedic character… It’s very different today. The Burns and Allen show and Jack’s show were essentially one-man operations. Nowadays there are literally dozens of people grouped around TV shows, and to get a comedy idea past them, you have to run a gauntlet. And in those days we were enjoying our work. It’s not fun anymore. One guy’s there saying, ‘You’re going overtime,’ another guy’s there saying, ‘You’re over budget,’ everybody’s tensed up and nervous. Oh, sure we had plenty of our own crises, but they were usually constructive ones, based on doing the best possible show we were capable of.”

American Bandstand, 30th Anniversary

On February 20, 2013

- TV History

American Bandstand, 30th Anniversary Finale!

A one of a kind band of 20+ ALL STARS of is chosen and the best of the best is playing with the late Bill Haley. The video cut ins of the live version of ‘Rock Around The Clock’ and Haley’s performance are great. Enjoy!

CLASSIC: ‘Requiem For A Heavyweight’October 11, 1956, ‘Playhouse 90’

On February 19, 2013

- TV History

CLASSIC: ‘Requiem For A Heavyweight’ RESTORED TELEVISION

October 11, 1956, ‘Playhouse 90’ presented ‘A Requiem For A Heavyweight’ written by Rod Serling.

The 90 minute, live teleplay won a Peabody Award, the first given to an individual script, and helped establish Serling’s reputation. The broadcast was directed by Ralph Nelson and is generally considered one of the finest examples of live television drama in the United States, as well as being Serling’s personal favorite of his own work. Nelson and Serling won Emmy Awards for their work. Six years later, it was adapted as a 1962 feature film starring Anthony Quinn, Jackie Gleason and Mickey Rooney.

In the photo above, Ed Wynn and his son Keenan Wynn sit with Jack Palance during the final dress rehearsal. The camera is an RCA TK11. Below the full restored historic live broadcast!

New York Islanders Hockey: Behind The Scenes

On February 18, 2013

- TV History

New York Islanders Hockey: Behind The Scenes

Very good video and even goes into depth on the back and forth communications between the announcers and the truck. Enjoy!

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=LJF-gBw2gk0

In this very special behind the scenes piece, you see just how the Islanders broadcast gets on to television each night. Features Deb Placey as the host.

March 19, 1953: First Coast To Coast Academy Awards

On February 18, 2013

- TV History

March 19, 1953: First Coast To Coast Academy Awards

Prior to this, the broadcast could only be seen live in the Los Angeles area, but in late 1952, that changed when AT&T finished the final links of the cross country coax and relay stations.

This is also the first bi coastal broadcast as well, with simultaneous ceremonies in New York and Los Angeles. Since this had never been done before, NBC held several days of rehearsals live in both cities to get the switching down on the coast to coast hookup.

The RCA Tri – Color Vidicon Camera: 1953

On February 18, 2013

- TV History

The RCA Tri – Color Vidicon Camera: 1953

Although RCA poured millions into this experimental project from ’53 till ’55, in the end they had to let it go. It worked, but not as well as they had hoped. Here are the details on the Tri – Color Vidicon.

This is a single tube capable of generating all three primary colors. The heart of the tube is a unique and intricate color sensitive target consisting of nearly 900 fine verticle strips of red, green and blue color filters covered by three sets of semitransparent signal conducting strips.

The signal strips, connected to corresponding to a given color, are all connected to a common output terminal and insulated at the same time from the strips of the other two colors. As the target is scanned by a single electron bean at the rear of the tube, the color sensitive filters permit the signal strips to produce electrical signals corresponding to the light and color of the image being scanned. Since the beam strikes all of the color sensitive strips at each scanning, three simultaneous color signals are generated.

Page 118 of 136

« Previous

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

30

31

32

33

34

35

36

37

38

39

40

41

42

43

44

45

46

47

48

49

50

51

52

53

54

55

56

57

58

59

60

61

62

63

64

65

66

67

68

69

70

71

72

73

74

75

76

77

78

79

80

81

82

83

84

85

86

87

88

89

90

91

92

93

94

95

96

97

98

99

100

101

102

103

104

105

106

107

108

109

110

111

112

113

114

115

116

117

118

119

120

121

122

123

124

125

126

127

128

129

130

131

132

133

134

135

136

Next »