- Home

- TV History

- Network Studios History

- Cameras

- Archives

- Viewseum

- About / Comments

Skip to content

Director Drew Esocoff

Photo: NBCU Photo Bank

Director Tony Verna

Photo: Courtesy Tony Verna

Director Doug Wilson

Photo: Courtesy Doug Wilson

Director Joe Aceti

Photo: DGA

Then and Now: The first game broadcast only used two cameras.

Photo: NBU Photo Bank

Director Ted Nathanson

Photo: Courtesy Edith Nathanson

ABC’s Roone Arledge, with NFL Commissioner Pete Rozelle,

introduced Monday Night Football.

Photo: AP Photo

Director Chet Forte

Photo: Mario Ruiz/Time Life Pictures/Getty Images

Director Bob Fishman

Photo: DGA Archives

Bird’s-Eye View: Directors today command an arsenal of digital tools including

computer-controlled Skycams suspended on a thin wire above the field.

Photo: George Gojkovich/Getty Images

Director Mike Arnold

Photo: John P. Filo/CBS

Posts in Category: TV History

Page 59 of 136

« Previous

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

30

31

32

33

34

35

36

37

38

39

40

41

42

43

44

45

46

47

48

49

50

51

52

53

54

55

56

57

58

59

60

61

62

63

64

65

66

67

68

69

70

71

72

73

74

75

76

77

78

79

80

81

82

83

84

85

86

87

88

89

90

91

92

93

94

95

96

97

98

99

100

101

102

103

104

105

106

107

108

109

110

111

112

113

114

115

116

117

118

119

120

121

122

123

124

125

126

127

128

129

130

131

132

133

134

135

136

Next » The ESPN/Chapman Dualie…

On September 23, 2014

- TV History

The ESPN/Chapman Dualie…Last Night In New York

In case you’ve never seen this, here is the coolest sideline ride in the business. This two level configuration is around four years old…the original version had both cameras mounted on a T bar and debuted around six years ago. The Metlife photo is from our friend Teddy Flandreau at last nights Bears – Jets game. Final score, Chicago 27, Jets 19. Enjoy and share! -Bobby Ellerbee

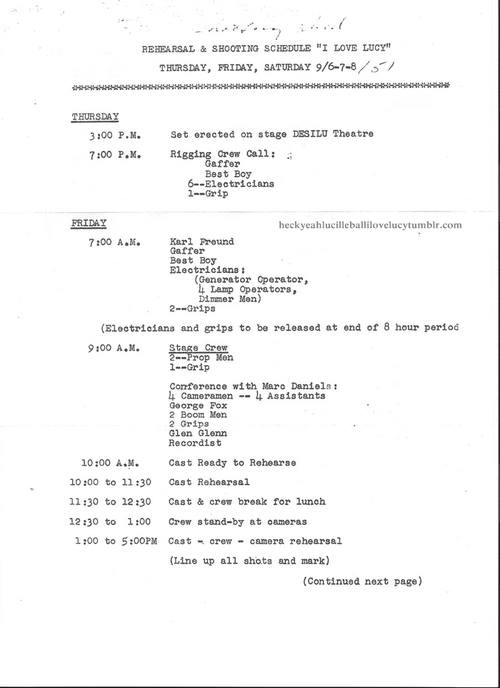

The First ‘I Love Lucy’ Episode Filmed…With Schedule

On September 22, 2014

- Archives, TV History

When ‘I Love Lucy’ debuted October 15, 1951, the first episode to air was “The Girls Want To Go To A Nightclub”, but the first episode to be filmed was “Lucy Thinks Ricky Is Trying To Murder Her” which was filmed on September 8, 1951. It aired as the fourth episode on November 5th.

This rare schedule shows the rehearsals and shooting times at The General Services Studios location, which is where the show was done for the first three seasons. Enjoy and share! -Bobby Ellerbee

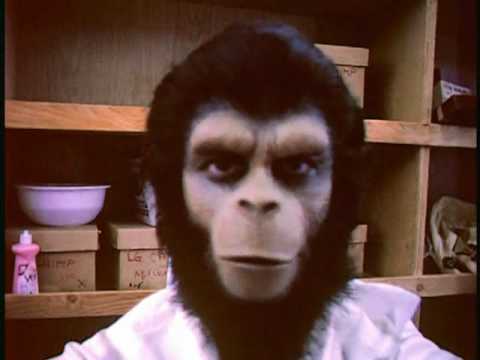

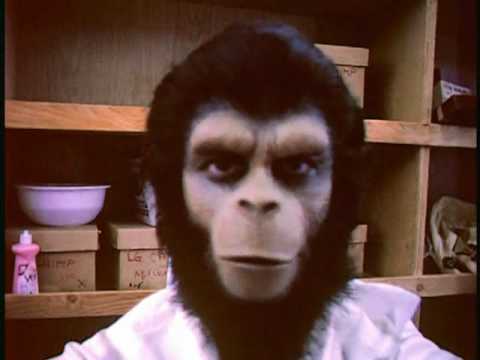

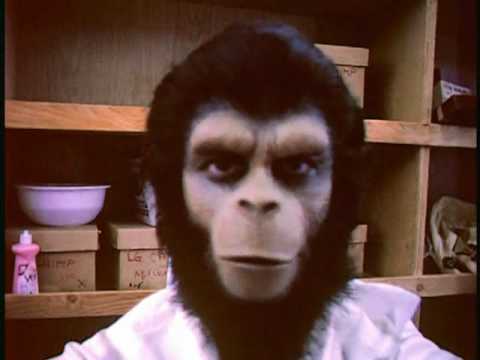

WOW! Roddy McDowall’s Home Movies…’Planet Of The Apes’

On September 22, 2014

- TV History

WOW! Roddy McDowall’s Home Movies…’Planet Of The Apes’

Thanks to Mike Clark for sending this amazing link to us. The first 8 minutes show Roddy being transformed into “Cornelius” in the makeup trailer at 20th Century Fox, but then he takes a helicopter to the set which gives us a great look at the Fox studios.

Mike points out that at 9:20, you can see the full-sized ‘Lost In Space’ Jupiter II mockup from the 3rd season episode “Visit to a Hostile Planet.” At the oceanfront set, we almost all of the principals, including Charlton Heston. Enjoy and share! -Bobby Ellerbee

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=lCm74dnwujk

Roddy McDowall’s home movies showing Don Cash applying his Cornelius make-up for original “Planet Of The Apes” (1968) http://www.imdb.com/name/nm0143587/

A Rare Look At The First Ikegami Color Studio Camera…The TK 301

On September 22, 2014

- TV History

A Rare Look At The First Ikegami Color Studio Camera…The TK 301

It’s good thing our Australian pals had a few too many pints one night in the early 70s, otherwise, we would not have had what I think is only the second video sighting of the first Ikegami color studio camera.

This is a “love story” between an Ikegami HL 77 and the TK 301. This was shot at the GLV8 studios and the only other surviving video of an Ikegami TK 301 also comes from there on a studio tour video that I have posted here in the past. The TK 301 and TK 355 were the only two TK models made by Ikegami before they changed to the HK prefix.

By the way, HL is short for their portable “Handy Looky” line and HK is short for “Handy Kamera”. The RCA TK prefix is thought to stand for “Television Kamera”…Kamera is the Russian spelling of camera and is thought to have come from Vladimir Zworykin. Thanks to Steve Bradford for the clip. Enjoy and share! -Bobby Ellerbee

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Z6Ax8PaCTfQ

This is a love story we put together one friday night after the pub. It was created by myself and a very talented cameraman Michael Maxwell. It’s a love stor…

This is my show…

On September 21, 2014

- TV History

‘Squidbillies’…Season 8 Debuts On Adult Swim Tonight At 11:45

This is my show! I am the voice of Sheriff on ‘Squidbilles’…television’s fourth most watched animated series. That’s a pretty good trick considering the other three are on Fox tonight in primetime!

Since our demo is mostly men 18 to 34, most of you have not seen the show, but millions of fans worldwide have. No matter your age, it’s still funny. By the way, Adult Swim is actually The Cartoon Channel after about 9PM. As the name Adult Swim implies, our shows are for adults only and have a lot of adult language and topics as you’ll see and hear.

I can not begin to tell you how much fun I have had playing this role. Since 2006, without fail, every single recording session has had at least one “laugh so hard you cry” moment and usually more. There is well over three hours of me just laughing uncontrollably in the archives. I love Sheriff…he is me and I am him in many ways, and I am honored to be us.

If you can’t make it till 11:45 tonight, set your DVR and take a look. Enjoy and share! -“Sheriff” Bobby Ellerbee

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Lpq5lJMMyvk

The Sheriff introduces Early and Granny to the wonders of the holodeck. SUBSCRIBE: http://bit.ly/AdultSwimSubscribe About Squidbillies: Squidbillies is Adult…

Directing Football…1939 Till Now! GREAT DGA ARTICLE!

On September 21, 2014

- Archives, TV History

This is the history of football on television as told by some of the greatest ever producers and directors including Chet Forte, Roone Arledge, Ted Nathanson, Drew Esocoff, Tony Verna, Doug Wilson, Joe Acenti, Bob Fishman and Mike Arnold.

This is a must read article written by David Davis for The Director’s Guild Of America’s “DGA Quarterly” Magazine, and covers the topic from A to Z and then some, with things we never knew about how it was all done including the first instant replays and much more. Enjoy and SHARE! -Bobby Ellerbee

http://www.dga.org/Craft/DGAQ/All-Articles/1103-Fall-2011/Television-Football.aspx

Calling the Plays

From the first primitive broadcast in 1939 to the Super Bowl and Skycams, directors have helped invent football on TV. But even with today’s arsenal of tools, the goal remains the same—capturing the action for viewers at home.

By David Davis

Photo: James D. Smith/AP Photo

There was less than one minute remaining in Super Bowl XLIII in 2009. The Pittsburgh Steelers trailed the Arizona Cardinals by three points, but they were mounting a final, desperate rally. The ball rested on the 6-yard line. Every fan inside Raymond James Stadium in Tampa, Florida, all 70,774 of them, were standing and screaming.

In the parking lot next to the stadium, NBC Sports director Drew Esocoff stared at a bank of television monitors arrayed on a wall inside a gigantic production truck. At his command were 52 cameras positioned throughout the venue, images from which flickered on the screens in front of him. In his earpiece, Esocoff could hear the voices of announcers Al Michaels and John Madden describing the action to the 98.7 million Americans watching on television.

The ball was snapped, and Pittsburgh quarterback Ben Roethlisberger went back to pass. Esocoff peered at the monitor showing the live shot of the game while letting his peripheral vision soak in the images flashing on the surrounding screens. He watched as Roethlisberger set himself and hurled the ball toward wide receiver Santonio Holmes, who stretched for the pass in the back corner of the end zone before being pummeled to the turf.

The play ended so abruptly that it was impossible to tell, in real time, what had happened. The fate of the Super Bowl was in the balance: Had Holmes managed to catch the ball and get both feet down, inbounds, and in the end zone, or not?

Director Drew Esocoff

Photo: NBCU Photo Bank

As Michaels and Madden began to debate the issue, Esocoff and producer Fred Gaudelli replayed over and over the sequence from multiple angles and perspectives: from an overhead camera and from both sides of the end zone; from a high-speed camera on a sideline cart that showed the play in super slow motion; from a handheld camera that gave a “defining shot” of Holmes with his feet in the end zone—barely—and clutching the ball.

Then, in a series of rapid-fire cuts, Esocoff used his other cameras to expand the story line. As the two teams awaited the final verdict, Esocoff followed the referee who was consulting a video monitor on the sideline to study the replays captured by the camera crew, then showed reaction shots from the opposing sidelines. Finally, after the referee ruled that the pass was complete, Esocoff toggled between thrill-of-victory and agony-of-defeat shots.

“The losers are sometimes a better visual than the winners,” Esocoff later explained. “We try to pay attention to both sides of every story because you don’t want to get sucked into the mentality that it’s all about the winners.”

Kickoff: The first professional broadcast was in 1939, but the game

that put the sport on the TV map was the NFL Championship

in 1958, often called the “Greatest Game Ever Played.”

Photos: (top) NBCU Photo Bank, (bottom) Robert Riger/Getty Images

Esocoff and his directing peers at Fox and CBS occupy a unique niche. Their three-hour live broadcasts are among television’s most valuable properties. Every week they entertain tens of millions of viewers during the National Football League’s 16-game regular season schedule, the playoffs, and the Super Bowl. In addition, because the footage produced by their cameras helps determine the outcome of each game, everyone with a stake in the NFL—players, coaches, officials, league executives, team owners, media, fans, and fantasy football players—scrutinizes every frame of their work as if it were the Zapruder Film.

It’s a juggling act that requires, simultaneously, intense preparation, artistry, and the ability to improvise under real-time conditions. “Directing the NFL is all about servicing the viewer,” Esocoff explains. “It’s about the personalization of the players and keeping everything focused on the field as best you can. It’s about the documentation of the game—that’s why people watch.”

Directing professional football has come a long way since its inauspicious debut in October of 1939, when the Brooklyn Dodgers defeated the Philadelphia Eagles. From inside a mobile unit parked outside Ebbets Field, director Burke Crotty had two iconoscope cameras at his disposal—and the camera positioned on the field was immobile. The game was shown only on NBC’s experimental station W2XBS in New York; perhaps 1,000 people viewed the broadcast.

The short-lived DuMont Television Network showed NFL games during the mid-1950s, before CBS took over the NFL’s broadcasting chores in 1956. At the time, baseball was the No. 1 sport in the United States. College football was much more popular than the professional version. The Super Bowl and its Roman numerals did not exist, nor did sideline reporters and halftime shows featuring pop stars and “wardrobe malfunctions.” Instant replay had yet to be invented.

Then came the game that changed everything, what is often called the “Greatest Game Ever Played.” The date was Dec. 28, 1958. The place was Yankee Stadium, where the New York Giants were hosting the Baltimore Colts for the NFL Championship.

NBC used four stationary cameras—five, if you count the fixed camera aimed at an easel with cards that read “First Quarter” and the like. The control booth was set up in the back of a van in a parking lot outside the stadium. The game did not pause for TV commercials, and no microphones were allowed on the field to record the sounds of the players. Viewers saw the action in black and white.

Director Tony Verna

Photo: Courtesy Tony Verna

“By today’s standards, it was a nothing broadcast,” remembers pioneering director Tony Verna, who began directing live sports events in the late 1950s and earned a DGA Lifetime Achievement Award for sports in 1995. “It was quaint.”

At a crucial moment late in the game, the rocking of the stadium knocked out an electrical cable, causing television screens across the nation to blacken. An NBC employee ran onto the field, pretending to be a deranged fan, so as to delay the proceedings and enable the network’s technicians to re-establish their live feed with only one missed play.

Still, an estimated 45 million fans tuned in for the Colts-Giants game. It opened the media’s eyes—as well as the “mad men” selling advertising on Madison Avenue—to the awesome potential of the NFL. “A seismic shift in the American sports landscape had clearly begun,” commented Michael MacCambridge, author of America’s Game: The Epic Story of How Pro Football Captured a Nation.

Charged with capturing pro football’s unique combination of physical mayhem and emotional resonance was a new generation of Guild sports directors, including Verna and CBS colleague Bob Dailey, NBC’s Ted Nathanson and Harry Coyle, and ABC’s Andy Sidaris, Jack Lubell, Bill Bennington, and Malcolm Hemion (brother of noted TV director Dwight Hemion). They faced myriad logistical challenges—besides, that is, filming in subzero temperatures in Green Bay and Chicago during December. Unlike in baseball or basketball, helmets and face masks hide football players’ facial expressions. Multiple cameras are needed just to cover the breadth of the playing surface (which measures 120 yards long by 53 yards wide). Most important, in a sport based on sophisticated and well-choreographed offensive and defensive schemes, directors could not isolate on individual matchups—the game within the game—with their “high” cameras positioned above the field.

Director Doug Wilson

Photo: Courtesy Doug Wilson

“The wider you are [with your cameras], the better you can document what’s happening competitively,” says longtime director Doug Wilson, who started with ABC’s Wide World of Sports in the early 1960s. “But that’s less exciting for the viewer because you lose the sense of speed and intimacy. The challenge for the football director is to have the audience feel intimate with the game and, at the same time, be wide enough to show what’s going on.”

That dilemma was exacerbated by the power of lenses in the early 1960s—or, rather, the lack thereof. “When we first started, I don’t think [the zoom lens] was even 20-to-1,” says Wilson, a DGA Lifetime Achievement in sports honoree in 1993. “You didn’t have the opportunity, with the camera on the coverage side of the field, to pick out the eyeballs of the coach on the other side. Today, that’s just magic in terms of telling the story of the game. We take all that for granted now.”

In those early years, Verna says, NFL teams were reluctant to embrace television. “It was very difficult to do anything innovative,” he says, “because the climate was different. The teams didn’t give [our camera operators] good positions on the field. We didn’t have the freedom to move around. Our cameras were on turrets that were bolted down.”

Director Joe Aceti

Photo: DGA

The directors also had to deal with the downtime between plays, often as long as half a minute. “They used to show both teams’ huddles for the whole 30 seconds,” says the late Joe Aceti, the 2006 DGA Lifetime Achievement in Sports Direction recipient, who directed football for CBS, NBC, and Fox. “That gets dull. It’s called television for a reason. It’s about pictures. You want to see pictures of action.”

In an effort to make the broadcasts more exciting, Verna, an inveterate tinkerer, began experimenting with a supply of newly minted Ampex videotape machines. (Television had moved to videotape from film in the late 1950s.) In December of 1963, just days after the televised coverage of the assassination of President John F. Kennedy, Verna unveiled the feature that would revolutionize football, and sports, on TV: instant replay.

Its inaugural use was anything but smooth. During CBS’ broadcast of the annual Army-Navy football game, Verna “instantly” replayed a touchdown run that had just been scored. As the black-and-white pictures flickered onscreen, announcer Lindsey Nelson screeched: “This is not live! Ladies and gentlemen, Army did not score again!”

Aceti remembers that, during the mid-1960s, “it was hell doing replays during live telecasts because it took so long. The tape was 2 inches wide, and you couldn’t see the picture when the tape was rewinding. You had to find it, queue it up, then back off 10 seconds to allow the tape to lock in [during playback]. You didn’t have time to get a lot of replays on the air, except at halftime.”

Then and Now: The first game broadcast only used two cameras.

Photo: NBU Photo Bank

As the technology improved, directors integrated more isolation shots and replays (oftentimes in slow motion) into their broadcasts. This gave TV viewers unique angles on the action—and announcers more fodder to explain the strategic matchups. “Fans on the couch could see what actually happened during the play: how the receiver got open, how the offensive line blocked,” says Verna.

Watching football on television began to outstrip the experience at the stadium. And, during the 1960s, money cemented the symbiotic relationship between professional football and television. NFL Commissioner Pete Rozelle persuaded CBS to pay $4.65 million for the annual rights to broadcast the league’s games in 1962. Just two years later, CBS agreed to pay $14.1 million per season, with the money equally divided among the league’s teams. Meanwhile, ABC was televising the fledgling American Football League under a five-year, $8.5-million contract that ensured its survival. In 1965, NBC wrested away the AFL package with a five-year deal worth a reported $42.5 million.

“The NFL and television—it’s a marriage,” says Aceti. “Pro football is the biggest moneymaker in all of sports. And, without tele-vision, the NFL wouldn’t be half the moneymaking machine that it is.”

In 1966, after the NFL and the AFL merged, Rozelle matched the two league champions in a winner-take-all playoff. For the TV rights to this new title game, he persuaded NBC and CBS to each pay $1 million. They agreed to simultaneously broadcast the game, using CBS’ feed, on Jan. 15, 1967.

Director Ted Nathanson

Photo: Courtesy Edith Nathanson

Dailey handled CBS’ directing effort, while Nathanson, who received a DGA Lifetime Achievement in Sports Direction award in 1991, helmed for NBC. According to Brought to You in Living Color: 75 Years of Great Moments in Television & Radio From NBC by Marc Robinson, “Nathanson arranged to have as big a TV set as could be found mounted in the mobile production truck. He trained a camera on the screen, occasionally zooming in and beaming that tighter shot over the air. The confused CBS crew apparently couldn’t figure out how NBC managed to get its ‘exclusives.’”

The contest between the Green Bay Packers and the Kansas City Chiefs was played at a neutral site: the Los Angeles Memorial Coliseum. It didn’t come close to selling out, even with tickets priced at $12, $10, and $6. CBS charged $85,000 for a one-minute commercial. (In 2011, Fox sold 30-second advertising spots for Super Bowl XLV for approximately $3 million.)

Thus was born the first edition of what became known as the Super Bowl. The idea did not catch on, Wilson says, until January of 1969, when quarterback Joe Namath and the New York Jets defeated the Baltimore Colts. “That was a major jump forward in the appreciation of the Super Bowl,” he says. “From then on, it passed the World Series as the No.1 sports event for the country.”

ABC’s Roone Arledge, with NFL Commissioner Pete Rozelle,

introduced Monday Night Football.

Photo: AP Photo

Perhaps no figure was responsible for inventing modern sports on television more than Roone Arledge, ABC Sports chief and a Guild member from 1960 until his death in 2002. In a 1966 Sports Illustrated interview, he recalled, “When I got into it in 1960, televising sports amounted to going out on the road, opening three or four cameras and trying not to blow any plays…. We began to use cranes, blimps, and helicopters to provide a better view of the stadium, the campus, and the town. We developed handheld cameras for close-ups…. We asked ourselves: If you were sitting in the stadium, what would you be looking at? So our cameras wandered as your eyes would. Sound had been greatly neglected too. All they used to do was hang a mic out the window to get the roar of the crowd. We developed the rifle-type mic. Now you can hear the thud of a football when it is punted.”

Beginning in 1970, Rozelle and Arledge leveraged the league’s popularity and began airing the NFL in primetime. Arledge positioned Monday Night Football as more than just another game. It was “football as entertainment,” as he put it. “Football at night under the lights, helmets gleaming, uniforms dazzling. Even cheerleaders looked better under the lights.”

Director Chet Forte

Photo: Mario Ruiz/Time Life Pictures/Getty Images

Arledge charged director Chet Forte, a DGA Lifetime Achievement in Sports Direction winner in 2000, with making MNF look different. Forte fought the league to allow better access for his handheld and sideline cameras and employed a two-unit, nine-camera crew at a time when NBC and CBS were using five cameras. Said Forte, in an interview from 1972, “What I wanted to do on Monday Night Football was get away from the conformity of CBS and the dictum they laid down for their directors: a wide shot to a tight shot, a wide to a tight, over and over. I wanted to gain impact with enormous close-ups. I wanted to see all the action bigger…. More meaning by going tighter. It’s a little more strain on the cameramen, but they never complain.”

Forte developed his own style and was more concise and exact in the way he followed the action. And, of course, on Monday Night Football he had the advantage of having a broadcast booth unlike any before with the big personalities of announcers Frank Gifford, Howard Cosell, and Don Meredith.

“Roone [Arledge] made Monday Night Football a happening,” Wilson says. “He brought celebrities into the booth and pageantry to the games because he knew that would expand the audience beyond hard-core fans.”

The debut of Monday Night Football marked the moment when the NFL crossed over to the mainstream. And, with technological improvements during the 1970s and 1980s, football on TV turned into a director’s medium. The first generation of directors didn’t have the equipment to really capture the game, but with the advent of better cameras and lenses, the development of the Steadicam, and more experienced engineering crews, football broadcasts continued to improve. Eventually, even the NFL, which was initially resistant to granting access to camera crews, let the directors set up where they wanted to.

Sandy Grossman became CBS’ lead director, as Nathanson continued his successful run on NBC. Meanwhile, as the dominance of the Big Three networks faded, the NFL expanded to cable with the emergence of all-sports powerhouse ESPN in the 1980s.

Today, NFL games are seen on CBS, NBC, Fox, and ESPN, which took over the Monday Night Football franchise from ABC. (Disney owns both ABC and ESPN.) Satellite provider DirecTV is part of the mix, and the league owns and operates Culver City, Calif.-based NFL Network, which airs a slate of games on Thursday nights. All of which has meant more work for, and competition among, today’s directors, including Richard Russo and Artie Kempner at Fox, Bob Fishman and Mike Arnold at CBS, and Esocoff at NBC.

Director Bob Fishman

Photo: DGA Archives

These directors still rely on their “high cameras,” positioned above the sidelines, to follow the action on each play. But football on TV in 2011 looks very different from anything Roone Arledge might have imagined. “It’s night and day from before,” CBS’ Fishman says. “When I look back at games from the 1980s and 1990s, it’s like the Dark Ages.”

Fishman and his contemporaries now command an arsenal of digital tools. For instance, on a thin wire suspended above the field are computer-controlled Skycams that require a three-person crew to operate. (The Skycam was invented by Garrett Brown, who also devised the Steadicam.) Directors can opt to freeze and spin the picture 180 degrees to show another perspective. For replays, they can access super slow-motion cameras that shoot up to 1,000 frames per second.

Bird’s-Eye View: Directors today command an arsenal of digital tools including

computer-controlled Skycams suspended on a thin wire above the field.

Photo: George Gojkovich/Getty Images

Perhaps the most significant improvement in equipment, Kempner says, involves the power of the Zoomar lenses. “When I started directing [in the 1980s], if you had a 55:1 lens, man, that was big,” he says. “Now, we’ll have eight different 100:1 lenses. We’re able to present the game to the viewer in a way that they’re going to get closer and understand it better. If you really want to see the game, you have to watch it on television.”

The crystal-clear images that appear on viewers’ 60-inch high-definition sets are complemented by an array of graphics packages, including the ubiquitous bright yellow first-down line. The constant clock and score provide fans with up-to-the-second information, while updates from other games crawl at the bottom of the screen. The Dolby Digital 5.1 audio system captures a soundscape of bone-jarring tackles.

The high-definition format is “an unbelievable asset,” Russo says. “We’re shooting 16:9 now [versus the long-established 4:3 format], so we’re shooting on a wider screen than before. If a camera operator is isolating on a wide receiver, he has to make sure the [defensive] cornerback is in the frame. At the same time, you have to work the tight shots and the emotional shots, whether it’s on the field or on the sidelines, so that you can bring the players’ reactions to the viewer.”

For directors accustomed to pacing their broadcasts to the rhythm of the game, the technological toys present their own challenge. “The broadcasts are more graphics and effects-driven than ever before,” says Fishman. “You’re always in a hurry to go to the next package, to show multiple replays of the same play, to send it back to the studio for an update.”

Russo, who directed the Super Bowl broadcast in 2011, preaches patience. “The audience doesn’t know where you’re about to go, but the audience knows where you’re leaving,” he says. “If you have a great reaction shot—whether it’s dejection or jubilation—be patient with that. Don’t be in a hurry to go somewhere else. All that matters is the moment.”

NBC’s Esocoff agrees, recalling that, after quarterback Brett Favre threw the last pass of his career in 2010, he stayed with the camera that showed Favre dramatically walking off the field alone. “The best thing that you learn is to slow down. Cutting more isn’t always better, and sitting on a shot for a little longer may be better,” he says.

The networks previously tried to juice their football broadcasts by attaching miniature cameras to players’ helmets and to the referee’s cap. GPS was also used briefly. Those failures showed only the limitations of technology over the human element.

Director Mike Arnold

Photo: John P. Filo/CBS

On the horizon is 3-D. “You have to approach it in a different way,” says Arnold, who directed a pre-season game in 3-D last year. “You need different camera positions and have to frame things differently. Extreme close-ups don’t work in 3-D, and you need lower play-by-play positions. If you’re too high, you lose the 3-D aspect.”

Regardless of what technical advances may be ahead, directors preach that old-fashioned preparation trumps digital bells and whistles. Kempner spends the week memo of every player to improve his reaction time in the truck. “When you’re directing live, you have no time to look down at your flip card,” he says. “You’ve got your eyes on the monitors. So, when [announcer] Thom Brennaman says, ‘The tackle was by Gilbert Smith,’ who wears number 92, I can instantly say, ‘[Camera] two, give me 92 blue.’

The director’s most important tool remains his crew. Arnold, who directed Super Bowl XLIV, coordinates every facet of the broadcast with his producer, DGA member Lance Barrow. They spend the week before each game speaking with their associate directors, camera operators and announcers, and the statisticians and graphics experts. They watch hours of game film to learn the offensive and defensive tendencies of the opponents, attend practices of both squads, and interview coaches and key players. They scour team and league websites for updated injury reports and monitor players’ Twitter accounts for any incendiary quotes.

“The producer is like the head coach who formulates the overall game plan,” Arnold says. “The director is like the quarterback. It’s my job to execute the game plan.”

Well before the opening kickoff, Arnold and Barrow coordinate the camera positions inside the stadium. The networks use 8 to14 cameras per game; Sunday night crews employ as many as 20. That number rises during the playoffs, climaxing with more than 50 for the Super Bowl.

“We discuss how we’re going to show the game on TV,” Arnold says, “because we’re trying to put the viewer in the best seat in the house. If one team likes to run the ball, we want to make sure we have cameras isolated in the middle of the line to see how the offensive line is opening up the holes.”

On game day, experienced directors have learned not to shape the broadcast to preconceived notions of how the game will turn out. Inclement weather or an injury can suddenly change the tenor of the action. “You can’t script a live event,” Russo says. “Once they kick off, you have no control. The most important thing is knowing the sport because it’s instinctive. You have to be able to react.”

“It’s a live event, so you only get one shot to get it right,” Arnold says. “I’m not minimizing what a film director does on the set, but if we miss a play, we can’t say, ‘The lighting wasn’t quite right. Can you run it again?’”

Fishman remembers the time his friend Francis Ford Coppola watched him direct from inside the production truck. “Francis said afterward, ‘We have the same job title, but our jobs are completely different,’” Fishman recalls. “He had no idea about the pressure we’re under on every play, how much stuff we’re looking at in real time, with no retakes. Then again, we don’t have to deal with any prima donna actors like Francis does.”

The prima donna factor surfaces only during the Super Bowl, when celebrities flock to the big game to hype their latest project. With producer Gaudelli, Esocoff is already planning NBC’s broadcast of the next annual extravaganza in February. He vows to keep his focus on the field. “We’re going to add cameras and graphics judiciously,” he says. “If you change everything you do just for the Super Bowl, you’re a step behind because what you’re used to looking over there to see is not there anymore. We’re not trying to reinvent the wheel.”

Calling the Plays – Directing Football

From the first primitive broadcast in 1939 to today’s Super Bowl, directors have helped create football on TV.

September 21, 1970…’ABC Monday Night Football’ Debuts

On September 21, 2014

- TV History

September 21, 1970…’ABC Monday Night Football’ Debuts

Most think this was a marriage made in heaven, but infact, it was really more like a shotgun wedding.

During the early 1960s, NFL Commissioner Pete Rozelle envisioned the possibility of playing at least one game weekly during prime time for a greater TV audience. While the NFL had scheduled Saturday night games on the DuMont network in 1953-1954, poor ratings and the dissolution of DuMont led to the series being eliminated by the time CBS took over the rights in 1956.

An early bid in 1964 to play on Friday nights was soundly defeated, with critics charging that such telecasts would damage the attendance at high school games. Undaunted, Rozelle decided to experiment with the concept of playing on Monday night, scheduling the Green Bay Packers and Detroit Lions for a game on September 28, 1964. While the game was not televised, it drew a sellout crowd of 59,203 to Tiger Stadium, the largest crowd ever to watch a professional football game in Detroit up to that point.

Two years later, Rozelle would build on this success as the NFL began a four-year experiment of playing on Monday night, scheduling one game in primetime on CBS during the 1966 and 1967 seasons, and two contests during each of the next two years. NBC followed suit in 1968 and 1969 with games involving American Football League teams.

During subsequent negotiations on a new television contract that would begin in 1970 (coinciding with a merger between the NFL and AFL), Rozelle concentrated on signing a weekly Monday night deal with one of the three major networks. After sensing reluctance from both NBC and CBS in disturbing their regular programming schedules, Rozelle spoke with ABC.

Despite the network’s status as the lowest-rated network, ABC was also reluctant to enter the risky venture. Only after Rozelle used the threat of signing with the independent Hughes Sports Network which was owned by reclusive businessman Howard Hughes, did ABC sign a contract for the scheduled games. Speculation was that had Rozelle signed with Hughes, many ABC affiliates would have preempted the network’s Monday lineup in favor of the games, severely damaging potential ratings.

ABC’s Roone Arledge had the job of making lemonade out of the lemons, and after the final contract for Monday Night Football was signed, he began to see the possibilities for the new show. Setting out to create an entertainment “spectacle” as much as a simple sports broadcast, Arledge hired Chet Forte, who would serve as director of the program for over 22 years. Arledge also ordered twice the usual number of cameras to cover the game, expanded the regular two-man broadcasting booth to three and used extensive graphic design within the show as well as instant replay.

Looking for a lightning rod to garner attention, Arledge hired controversial New York sportscaster Howard Cosell as a commentator, along with veteran football play-by-play man Keith Jackson. Arledge had tried to lure Curt Gowdy and then Vin Scully to ABC for the MNF play-by-play role, but settled for Jackson after they proved unable to break existing contracts with NBC Sports and the Los Angeles Dodgers, respectively.

Arledge’s original choice for the third member of the trio, Frank Gifford, was unavailable since he was still under contract to CBS Sports. However, Gifford suggested former Dallas Cowboy quarterback Don Meredith, setting the stage for years of fireworks between the often-pompous Cosell and the laidback Meredith.

Monday Night Football first aired on ABC on September 21, 1970, with a game between the New York Jets and the Browns in Cleveland and all that’s left of that video is posted below.

Advertisers were charged $65,000 per minute by ABC during the clash, a cost that proved to be a bargain when the contest collected 33 percent of the viewing audience. The Browns defeated the Jets, 31-21 in a game which featured a 94-yard kickoff return for a touchdown by the Browns’ Homer Jones and was punctuated when Billy Andrews intercepted Joe Namath late in the fourth quarter and returned it 25 yards for the clinching touchdown. However, Cleveland viewers saw different programming on WEWS-TV, because of the NFL’s blackout rules of the time which would apply for all games through the end of the 1972 season. Beginning in 1973, home games could be televised if they sold out 72 hours before kickoff.

Enjoy and share! -Bobby Ellerbee

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=mtZktj4exxc

First Monday Night Matchup between the Browns and the Jets. The great Keith Jackson on the mic with the late greats Howard Cosell and Don Meredith I OWN NOTH…

September 21, 1957…’Perry Mason’ Debuts On CBS

On September 21, 2014

- TV History

September 21, 1957…’Perry Mason’ Debuts On CBS

I have two rare videos to share with you on ‘Perry Mason’.

The first one (linked above) is Raymond Burr’s screentest for the lead role. This looks like a video tape, but could be a kinescope which was most likely shot at the CBS Television City.

Next up is a rare interview with Raymond Burr on the set, conducted by the well known Scottish born, Canadian journalist Jack Webster in 1963 when the show was in it’s seventh season. The original series would run for nine seasons and ended in 1966 after 271 episodes…one of which was shot in color. “Tale Of The Twice Told Twist” was the color episode and aired near the last of the final season in February of 1966. I think CBS ordered it as it considered extending the show for another few seasons.

The first ever episode of ‘Perry Mason’ that aired 57 years ago today was “The Case Of The Wrestles Redhead”.

To this day, ‘Perry Mason’ is still one of my all-time favorite shows. It was smart and well done. To me, the only thing that dates the show is the lack of cell phones…how many times could Perry and Paul have saved the day earlier by not having to stop at pay phone or call Della for messages? Enjoy and share! -Bobby Ellerbee

Seemingly born to play ‘Perry Mason’, Raymond Burr did have to test for the role. The woman playing ‘Della Street’ is a bit too provocative for the character…

September 21, 1948…Berle Named Permanent Host, ‘Texaco Star Theater’

On September 21, 2014

- TV History

September 21, 1948…Berle Named Permanent Host, ‘Texaco Star Theater’

On June 8, 1948, there were two major debuts at NBC’s 30 Rockefeller Plaza and they both happened in the same place at the same time as ‘The Texaco Star Theater’ was broadcast live from Studio 6B. This was the first broadcast from 6B after it’s conversion from radio to television studio.

On the first television broadcast of the ‘Texaco Star Theater’, Milton Berle was the host, but not the permanent host…there were rotating hosts in that June to September block of Tuesday night television including George Price, Morey Amsterdam, Peter Donald and Jack Carter.

66 years ago today, Milton Berle was named the permanent host of the show. When the show made its television debut in June of ’48, Berle was the host of the radio version which had been on the air since October of 1938 with Ed Wynn as host and star. In 1940, Fred Allan took over and after he left in ’44, succeeding hosts were James Melton, Tony Martin, Gordon MacRae, Jack Carter and Milton.

As Ed Wynn’s hit, the show became bankable, but as Fred Allen’s radio hit, ‘Texaco Star Theater’ was one of the most cleverly cerebral comedy-variety shows of its time. When it moved to television with Milton Berle, it proved a groundbreaker for two decades’ worth of television variety programming and, in the genius of Berle, gave the medium the first star it could call its own.

The television version allowed him the full spread of his visual and verbal talent, uniting them toward a height he couldn’t have achieved even in his legendary vaudeville and silent-screen days. Berle’s fame and stardom was quick and huge but…once television’s biggest single star, he also became the first TV personality to suffer from over-exposure and burnout.

At the link below, Milton Berle talks about the shows most memorable bloopers…and poopers as it turns out. These are great stories from the masters lips about the “doody bears” and how Red Buttons wound up stark naked on live TV! Enjoy and share! -Bobby Ellerbee

Thanks to NBCU Photobank for the photo.

NBC Studio 6A…The Meredith Viera Show

On September 20, 2014

- TV History

NBC Studio 6A…The Meredith Viera Show

It’s taken over a year, but it’s finally on the air in syndication. The only way I can see it in the Atlanta market is to DVR it…it comes on at 2:30 AM here on WSB, an ABC affiliate. Oddly, WSB runs two episodes of ‘Dr. Phil’ each afternoon but they are the most profitable TV station in the nation, so I guess they know what they are doing.

6A was home to David Letterman, Conan O’Brien and Jimmy Fallon with Fallon the only late show to come from 6B until the ‘Tonight’ show returned this year. Before Fallon took over ‘Tonight’, Dr. Oz was taping in 6A. After Oz left, the show moved to 6A so 6B and 8G could be totally redone. Oz has moved to ABC and has taken over the studio where Katie Couric’s show done.

Looks like there are two ped cameras, a jib and a hand held (covered up on the stand) and having seen the show, I can tell you there are at least three other fixed and rail cameras around. Enjoy and share! -Bobby Ellerbee

Home Of ‘Queen For A Day’…Moulin Rouge, 6230 W. Sunset Blvd

On September 20, 2014

- TV History

Home Of ‘Queen For A Day’…Moulin Rouge, 6230 W. Sunset Blvd

You can see the main room of The Moulin Rouge in the first few seconds of this video. NBC carried the show weekday afternoons at 1:30 from 1956 till 1960 when it moved to ABC and stayed on till ’64.

‘Queen for a Day’ began on the Mutual Radio Network on April 30, 1945 in New York City before moving to Los Angeles a few months later. Believe it or not, this series is considered a forerunner of modern-day “reality television”. The show became popular enough that NBC increased its running time from 30 to 45 minutes to sell more commercials, at a then-premium rate of $4,000 per minute.

The venue was originally The Earl Carroll Theater and opened

December 26, 1938 for lavish Earl Carroll musical comedy revues. The exterior featured a 20-foot high neon silhouette of Beryl Wallace, one of the Earl Carroll girls. Over the entrance doors it said: “Through these portals pass the most beautiful girls in the world.”

The theater was sold following the deaths of Earl Carroll and Beryl Wallace in an airplane crash. In 1953 it re-opened as the Moulin Rouge nightclub. Martin & Lewis, Red Skelton and many of the top performers of the 40s and 50s performed here as it was the largest nightclub in Los Angeles and on any given night, you could find a who’s who of movie stars there.

The club has had many names since, but below is a link to a video clip from 1966 announcing the opening of the Hullabaloo Club…I think you’ll find the names and faces familiar! Enjoy and share! -Bobby Ellerbee

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=jfpLw1uh2ac&feature=player_embedded

The Amazing Back Story Of ABC’s Vine Street Theater…1313 Vine Street

On September 20, 2014

- TV History

The Amazing Back Story Of ABC’s Vine Street Theater…1313 Vine Street

Did you know this was originally the home of The Don Lee – Mutual Network? Or, that this is the first place Johnny Carson ever went on network television?

The building was originally built in 1948 as a radio and television studio facility at a cost of $3 million. The dedication of the Don Lee-Mutual Broadcasting building was held on August 18, 1948. It is the oldest surviving structure in Hollywood that was originally designed specifically with television in mind.

Cadillac dealer Don Lee got into broadcasting to stay competitive with his friend Earle C. Anthony, a Packard dealer, who bought radio station KFI as a method of appealing to his customers. Lee bought KFRC in San Francisco and KHJ in Los Angeles, ultimately building the chain to 12 West Coast stations. Though named for him, Lee, who had died 14 years earlier, never saw this building.

The building was the original home of Los Angeles Channel 2, which is now KCBS-TV, through the 1950s. KCBS-TV is one of the oldest television stations in the world. It was signed on by Don Lee Broadcasting, and was first licensed by the FCC as experimental television station W6XAO in June 1931. The station went on the air on December 23, 1931, and by March 1933 was broadcasting programming one hour each day only on Monday through Saturdays.

During World War II, programming was reduced to three hours, every other Monday. The station’s frequency was switched from Channel 1 to Channel 2 in 1945 when the FCC decided to reserve Channel 1 for low-wattage community television stations. The station was granted a commercial license (the second in California, behind KTLA) as KTSL on May 6, 1948, and was named for Thomas S. Lee, the son of Don Lee.

Don Lee’s broadcasting interests were placed for sale in 1950 following the death of Thomas S. Lee. General Tire and Rubber agreed to purchase all of Don Lee’s stations, but chose to spin-off KTSL and the building at 1313 Vine Street to CBS. On October 28, 1951, KTSL changed its callsign to KNXT to coincide with CBS’ Los Angeles radio outlet, KNX (1070 AM). In April of ’84, it became KCBS.

These are the studios where Johnny Carson’s earliest mid-’50s television appearances, including ‘Carson’s Cellar’ and ‘The Johnny Carson Show’ were done. I had always thought they were from the Columbia Square studios a few blocks away.

ABC bought the building from CBS around 1967, installed GE color cameras and produced shows like ‘The Joey Bishop Show’, ‘The Dating Game’ and ‘The Newlywed Game’ from 1313 Vine Street.

Today, it is the home of the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Science’s Pickford Center for Motion Picture Study. It was dedicated in honor of legendary silent film actress Mary Pickford in 2002. Pickford was one of the founding members of the Academy. Enjoy and share! -Bobby Ellerbee

Ever See One Of These? This Is The GE PE 25 Color Camera

On September 20, 2014

- TV History

Ever See One Of These? This Is The GE PE 25 Color Camera

There are not many photos of this camera, but thanks to David Crosthwait at DC Video, we have a new black and white photo taken at KCOP in Los Angeles. The color photo (the only one we know of) shows our friend Mike Clark with a PE 25 at WCNY Syracuse NY. By the way, the Marconi Mark IVs in the background are from ‘The Ed Sullivan Show’….those are The Beatles cameras.

GE had a camera called the PE 15 that looked almost like this but it’s handles were at the top of the doors instead of underneath. This camera debuted in 1965 and as usual for GE cameras, were mostly used in west and southwest markets. If anyone know if one of these cameras survives, please let me know. Enjoy and share! -Bobby Ellerbee

In Case You Missed This…ABC Prospect, 1950 And Today

On September 20, 2014

- TV History

In Case You Missed This…ABC Prospect, 1950 And Today

A week or so back, I posted this shot from what we think is from ‘The Marshal At Gunsight Pass’…a 1950 western themed kids show done live Saturday afternoons for ABC’s west coast stations. It ran for 22 weeks and was pulled due to the expense and difficulty of adding the outside elements of the production.

Thanks to ABC veteran Charlie Henry, here is a recent picture of the same location we see in the old black and white shot, which is the parking lot at ABC’s Prospect Studios. Enjoy and share! -Bobby Ellerbee

UNBELIEVABLY RARE! The SHOW, The SCRIPT & SCHEDULE!

On September 19, 2014

- TV History, Viewseum

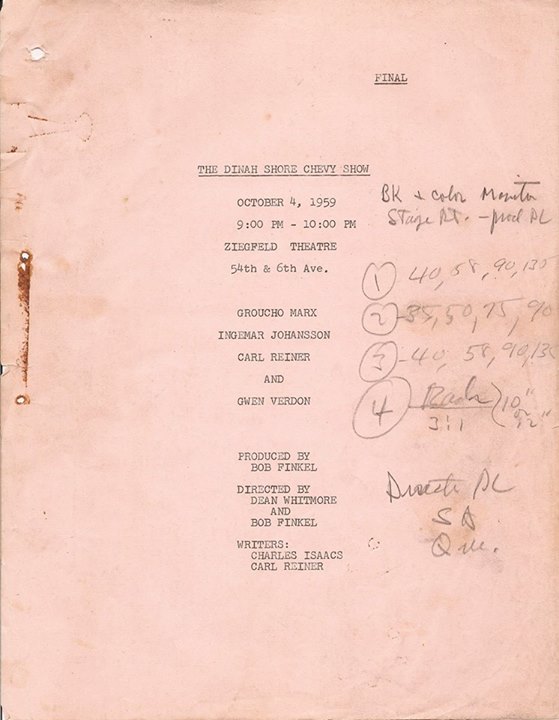

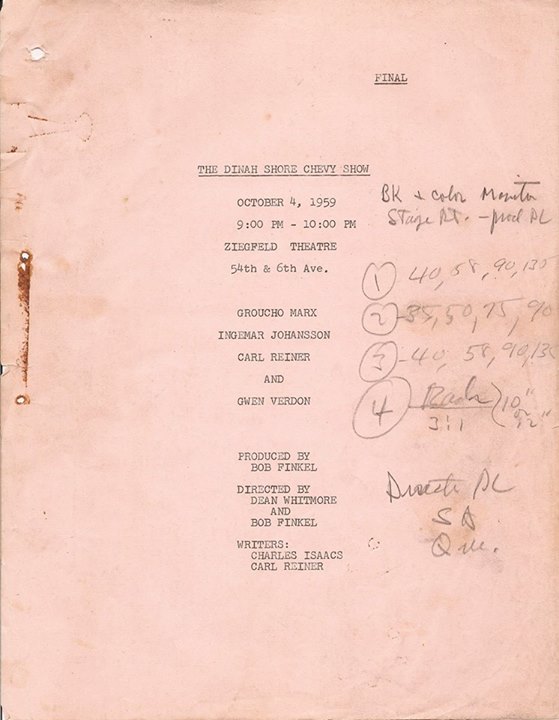

UNBELIEVABLY RARE! The SHOW, The SCRIPT & SCHEDULE!

On Sunday night at 9PM, October 4, 1959, ‘The Dinah Shore Chevy Show’ aired in color on NBC from The Zeigfeld Theater. Here is the whole show!

Below are a few pages of the script and the rehearsal sheets from this same show! Thanks to our friend Gady Reinhold at CBS, we are able to see these historic artifacts and with his notes, understand the meaning of some of the technical terms of the day. As you click on each image, you will see his descriptions of what is on each page. You will only see this here so please share this rarity! -Bobby Ellerbee

Dinah Shore With The Colonial Theater’s RCA TK40s…1957

On September 19, 2014

- TV History

Dinah Shore With The Colonial Theater’s RCA TK40s…1957

Continuing on the theme from the previous post of Peter Katz photo from The Colonial Theater, here is Dinah Shore with these rare cameras.

Notice the first camera we see had no vents on the viewfinder. This was how the first RCA TK40s were made. The four TK40s at The Colonial were the prototypes and these four were built in the fall of 1952. No more were made until RCA started the production line in late 1953 and even then, they only made 20 TK40s before switching to the TK41 in early 1954.

When they began building the TK41s, they added vents to the viewfinder enclosure and to the door over the high voltage box and sent out these modified pieces to The Colonial, KNBC in LA, WRC in Washington and WNBQ in Chicago. For some reason, one of the TK40s at the Colonial was never updated, but the others were. Enjoy and share! -Bobby Ellerbee

Adelphi Theater Stage Is Now…New York Hilton’s Grand Ballroom

On September 19, 2014

- TV History

Adelphi Theater Stage Is Now…New York Hilton’s Grand Ballroom

If you ever want to conjure up the ghosts of ‘The Honeymooners’, make your way to the Grand Ballroom of the New York Hilton as that is where the stage of the Adelphi Theater was located.

After I posted the rare new photo from Peter Katz yesterday of the ‘Honeymooners’, our friend Howie Zeidman from ABC called me with this interesting information. In the color photo, you see on the left what I think is the Hilton’s ballroom entrance which is directly across from the (new) Ziegfeld Theater at 144 W. 54 Street. The Adelphi was at 152 W. 54.

In the second photo, we see a long shot up 54th from 6th Ave. By the time this photo was taken, Dumont had moved out (1957) and the theater was renamed The 54th Street Theater. It was torn down in 1970 to make way for the Hilton.

Speaking of The Ziegfeld Theater, the one shown here is not the original theater where NBC did ‘The Perry Como Show’, but it is very close. That theater was on the corner of 6th Avenue and 54th street and this new Ziegfeld movie theater was built right behind where the original was.

By the way, CBS Studio 50 (Ed Sullivan Theater) is only a couple of blocks from here. Gleason started there with CBS in 1952 and had offices in the Park Sheraton Hotel which was only a block from Studio 50. When he decided to do the half hour ‘Honeymooners’ on film, he wanted something close and choose Dumont’s Adelphi which Dumont had just equipped with their new Electronicams. Enjoy and share!

-Bobby Ellerbee

‘Wheel Of Fortune’…Behind The Scenes, 1988 Part 2

On September 19, 2014

- TV History

‘Wheel Of Fortune’…Behind The Scenes, 1988 Part 2

This is great! We get to see how the letter board works and more of the TK47s in Studio 4 in Burbank, plus the M G Kelly announce opening with a classic RCA mic. In the latter half of this, we see Vanna and Director Dick Carson shooting openings in NYC for the upcoming Radio City Music Hall shows. Enjoy and share! -Bobby Ellerbee

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=_z6_DNHyqhQ

Aired November 12, 1988. Some of the backstage faces seen in this special are announcer M.G. Kelly, producer Nancy Jones, director Dick Carson (Johnny’s brot…

ULTRA RARE! For The First Time Anywhere!

On September 18, 2014

- TV History

ULTRA RARE! For The First Time Anywhere!

Although there are two similar photos of Jackie Gleason’s ‘Honeymooners’ being shot by these Dumont Electronicams, this one has never been seen before. It was taken by our new friend Peter J. Katz at the Adelphi Theater in November of 1955. The episode being filmed is Episode 7 of the “classic 39” titled ‘Better Living Through TV’ and up top is a link to the video. There is an extra bonus at 14:40 where a regular Dumont camera is on the set.

This photo is rare on many levels. Gleason usually did only one rehearsal and this was taken during that one runthrough of ‘Better Living’. In case you have never seen a Dumont Electronicam, this is a Dumont television camera with a Mitchell 35MM movie camera mounted along side and both are shooting through a shared lens.

In the photo, Ralph is trying to convince Alice to go along with him on yet another get-rich-quick scheme – selling Handy Housewife Helpers on TV…this comes at around 11 minutes in, in the video. This features a rare gone-wrong moment when one of the gadgets flies off the handle, forcing Gleason to retrieve it and then ad-lib his way back into the scene. When airtime comes, Ralph suddenly contracts a bad case of stage fright.

Soon, more rare photos from Peter J. Katz, all of which are copyrighted and we thank Peter for sharing. Enjoy and share! -Bobby Ellerbee

‘Wheel Of Fortune’…Behind The Scenes, 1988 Part 1

On September 18, 2014

- TV History

‘Wheel Of Fortune’…Behind The Scenes, 1988 Part 1

Tomorrow, I’ll post part two which follows the show to New York for a week of taping there, but for now…welcome to NBC Burbank Studio 4, which was also home to Dean Martin.

The cameras are RCA TK47s and we get a good look at the studio in the first minute and again just before the 7 minute mark. For Vanna White fans, there’s a lot of this Atlanta girl here to enjoy and, of the show’s producer Nancy Jones. Tomorrow, we meet the show’s director, Dick Carson…Johnny’s brother. Enjoy and share! -Bobby Ellerbee

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ryV1yGk4xz4

Aired November 12, 1988. Some of the backstage faces seen in this special are announcer M.G. Kelly, producer Nancy Jones, director Dick Carson (Johnny’s brot…

Page 59 of 136

« Previous

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

30

31

32

33

34

35

36

37

38

39

40

41

42

43

44

45

46

47

48

49

50

51

52

53

54

55

56

57

58

59

60

61

62

63

64

65

66

67

68

69

70

71

72

73

74

75

76

77

78

79

80

81

82

83

84

85

86

87

88

89

90

91

92

93

94

95

96

97

98

99

100

101

102

103

104

105

106

107

108

109

110

111

112

113

114

115

116

117

118

119

120

121

122

123

124

125

126

127

128

129

130

131

132

133

134

135

136

Next »