- Home

- TV History

- Network Studios History

- Cameras

- Archives

- Viewseum

- About / Comments

Skip to content

Posts in Category: TV History

Page 73 of 136

« Previous

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

30

31

32

33

34

35

36

37

38

39

40

41

42

43

44

45

46

47

48

49

50

51

52

53

54

55

56

57

58

59

60

61

62

63

64

65

66

67

68

69

70

71

72

73

74

75

76

77

78

79

80

81

82

83

84

85

86

87

88

89

90

91

92

93

94

95

96

97

98

99

100

101

102

103

104

105

106

107

108

109

110

111

112

113

114

115

116

117

118

119

120

121

122

123

124

125

126

127

128

129

130

131

132

133

134

135

136

Next »

This Will Put A Lump In Your Throat…Ray Charles & Friends

On July 4, 2014

- TV History

This Will Put A Lump In Your Throat…Ray Charles & Friends

For many years, this has been my favorite rendition of this beautiful, patriotic melody. Ray Charles does for this song, what Whitney Houston did for the national anthem…bring it to life.

Ray is joined by Quincy Jones, Stevie wonder, Michael McDonald, Michael Bolton, James Ingram and more for his iconic performance of “America The Beautiful”. Turn it up, enjoy and share! Happy 4th!

The Story Of The Best Ever Version Of “The Star Spangled Banner”

On July 4, 2014

- TV History

To help set the tone for this 4th of July holiday, here is our national anthem sung like never before, and the backstory of how it came to be. Please watch it with the volume high and don’t be surprised if you tear up to, what most consider, the most moving rendition ever.

At this link is the ESPN Magazine article that gives us so much of the detail of the time and place…the very top of 1991. The article is like time travel itself for those of us who were alive then and a guide for those that were not. https://www.espn.com/espn/feature/story/_/id/14673003/the-story-whitney-houston-epic-national-anthem-performance-1991-super-bowl

Few know that the entire performance was prerecorded…music and voice. In order to keep the performance from sounding thin, as most stadium performances tend to be, Houston wanted the great arrangement by John Clayton to be as powerful and moving as it was when she first heard it ten days earlier.

This performance was the opening of Super Bowl XXV at Tampa Stadium, January 27, 1991…10 days into the Persian Gulf War. Whitney was backed by the Florida Orchestra along with music director Jahja Ling, before 73,813 fans, 115 million viewers in the United States and a worldwide television audience of 750 million.

When asked to perform, Houston knew instantly how she wanted to interpret the tune. Rickey Minor, her longtime musical director, suggested taking the song out of standard, waltz tempo—three quarters time—and add an extra beat per measure, which would allow Houston to open up her voice and the song. It worked!

Enjoy and Share! Happy 4th!

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=N_lCmBvYMRs

Among the annals of national anthems as a prelude to sporting events, few have topped the one delivered by Whitney Houston before Super Bowl XXV in 1991 in T…

‘All In The Family’ Weekly Run Down…

On July 3, 2014

- TV History

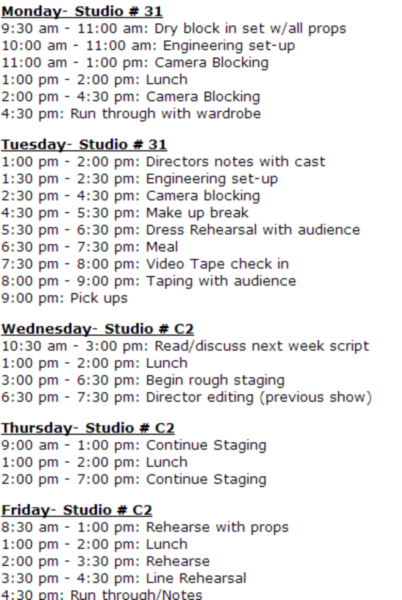

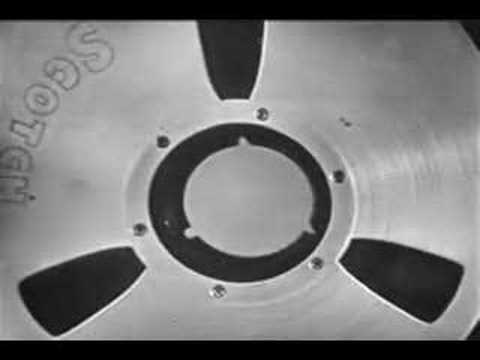

‘All In The Family’ Weekly Run Down…

Here’s a great television artifact from of of it’s biggest shows. As you can see, the show taped on Tuesday nights, which I think stayed constant at both Television City and Metromedia. Enjoy and share!

State Of The Art Television: 1961 & The Ampex Editec System

On July 3, 2014

- TV History, Viewseum

State Of The Art Television: 1961 & The Ampex Editec System

This great 1961 demo tape from KTTV in Los Angeles gives us one of the most thorough run throughs of video switching effects and video capabilities of that era available. Keep in mind though, videotape was still a cut and splice process till 1963 when Ampex introduced the Editec system which came after this video was created, but here’s the way it worked…

Editec was the first form of electronic video editing, allowing broadcast television editors frame-by-frame recording control, simplifying tape editing and the ability to make animation effects possible, but left a lot to be desired. They had no time code, no way to mark edit points, and no pre roll.

Just like the cut-and-splice technique, editors found edit points by stopping the tape near the start of a scene and fine-tuning the reel position by hand.

With points marked on both machines, they manually wound the tapes backward an equal number of control track pulses. Then they started both machines playing at the same time. At the edit point, they punched record on the master machine.

Two things determined whether the edit hit at the right time: the speed of the machine’s record switch, and the carefully-timed twitch of the editor’s finger.

If the editor hit the button early, or if the switch started recording a fraction of a second sooner than the editor guessed, the previous scene on the master got clipped.

If the edit happened too late, the editor had to decide if it was bad enough to take a second time. Repeating edits got tricky because the window to get it right grew narrower and narrower with each attempt. If the second try triggered too soon, it botched the master. If it triggered too late, it meant yet another try.

Typically, alert editors and reliable machines could get within a half-second of the intended edit point using this technique. Enjoy and share!

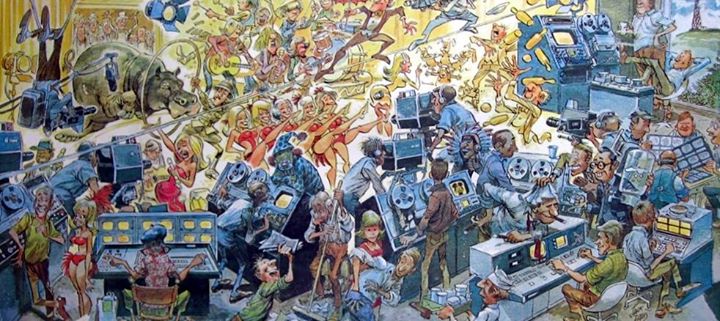

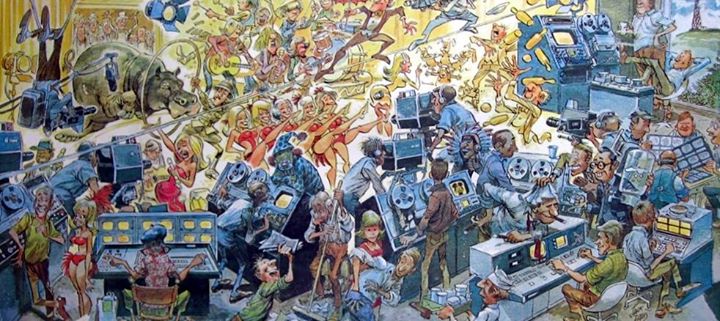

The Ampex NAB Poster By MAD Artist Jack Davis

On July 3, 2014

- TV History

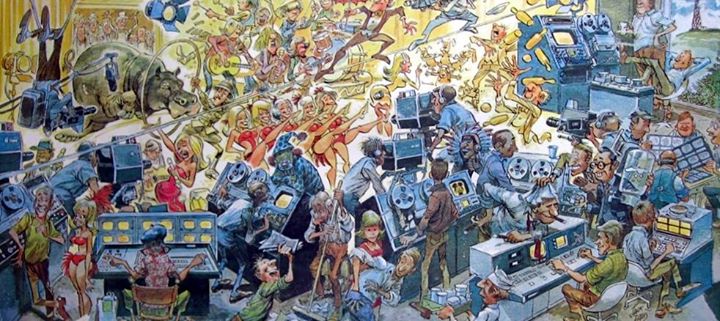

By Request…The Ampex NAB Poster By MAD Artist Jack Davis

Every once in a while, people ask me to post this and since we’ve been on the edge of Ampex land the last few days, here is the biggest and best image I can find of this. I think this was given out at the NAB back in the 70s.

In 1944, the Ampex Electric and Manufacturing Company was formed by Alexander M. Poniatoff in San Carlos, California. The name AMPEX consists Poniatoff’s initials…AMP, with with the EX added as an abbreviation for “excellent” to form the unique name.

The Oldest Surviving Color Videotape…May 22, 1958

On July 3, 2014

- TV History

The Oldest Surviving Color Videotape…May 22, 1958

This is the dedication of NBC’s new studios for WRC Radio and TV, it’s owned and operated station in Washington DC. President Eisenhower is on hand for the occasion as are David and Robert Sarnoff and many distinguished guests.

NBC’s David Brinkley narrates much of the opening minutes which gives us a good look at Studio A, while Eisenhower gets a tour of the engineering facilities. As you’ll see, mostly from 4:28 – 6:00 and again from 9:30 – 10:30, there are black and white cameras in the studio alongside two new RCA TK41s. Their four black and white cameras are in use mostly to cover the arrival and dignitaries, but when the speakers start, their job is done and the TK41s take over.

At 14:50, Robert Sarnoff pushes a big button to make the switch from b/w to color, which is when the color burst is added to the signal. This rare Quad tape restoration to D-2 digital tape was done by Ed Reitan, Don Kent, Dan Einstein in July of 2006.

For the behind the scenes story on the restoration and some interesting photos, go to this link…

http://www.quadvideotapegroup.com/EiesnhowerQuadRestoration.htm

Enjoy and share!

The Care And Feeding Of The Ampex VR 2000 Quad VTR

On July 2, 2014

- TV History, Viewseum

The Care And Feeding Of The Ampex VR 2000 Quad VTR

As your read this, quad video tape is being transferred to digital formats inside CBS Television City at what they like to call “Jurassic Park”. It’s a 24/7/365 operation and the facility is equipped with just about every type VTR format you can imagine.

In 1964, Ampex introduced the VR 2000 high band videotape recorder, the first ever to be capable of color fidelity required for high quality color broadcasting. Just for fun, here is part one of the three part Ampex training tape on the VR 2000. You can find the rest in YouTube.

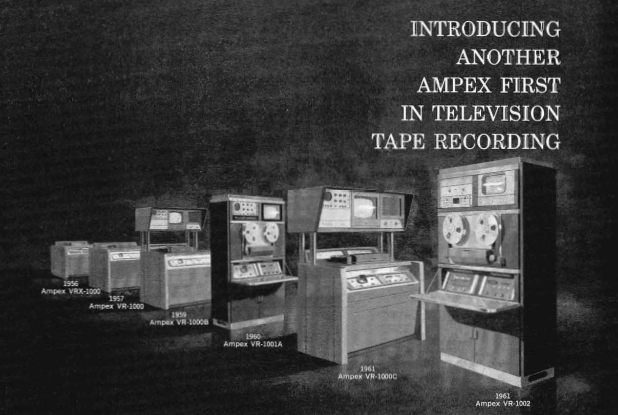

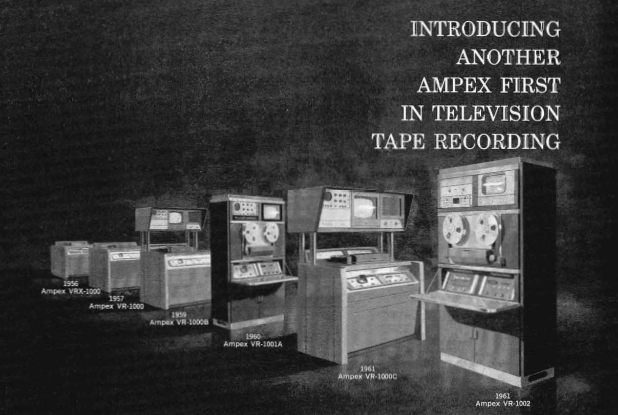

The Ampex Senior Class…1956 – 1961

On July 2, 2014

- TV History

The Ampex Senior Class…1956 – 1961

This 1961 ad from Ampex shows the first six videotape machine models they made…machines that changed the world. Here’s the lineup from left to right: 1956, the VRX 1000…1957, the VR 1000…1959, the VR 1000B…1960, the VR 1001A…1961, the VR 1000C and also from 1961, the VR 1002. Enjoy and share!

‘Concentration’…NBC, August 25, 1958 – March 23, 1973

On July 2, 2014

- TV History

‘Concentration’…NBC, August 25, 1958 – March 23, 1973

The original network daytime series, ‘Concentration’, appeared on NBC for 14 years, 7 months. With 3,796 telecasts, this was NBC’s longest running game show. Hugh Downs was the original host and served from ’58 till ’69. During this time, Hugh was also Jack Paar’s side kick on ‘Tonight’ and in ’62, he was the new anchor on ‘Today’ when Dave Garroway left. In ’85, The Guinness Book Of Records recognized Hugh Downs for holding the record for the greatest number of hours on network television.

It’s anybody’s guess as to where this photo was taken because ‘Concentration’ had a lot of homes, but the daytime version was always inside 30 Rock. From ’58 till ’65 Studio 3A was home. 1965 till 1967, it was 3B, and 8G from ’67 till ’73. This was the last show on the NBC roster to go color and that happened November 7, 1966.

There were two short lived night time versions…one was hosted by Jack Barry in 1958 for four weeks from Studio A at NBC’s 67th Street location, which was where the ‘Home’ show was done. The second primetime version was April to September of ’61 from the Ziegfeld Theater on Monday nights with Bob Clayton as host.

When Downs left in ’69, Bob Clayton took over, but three months later Ed Mcmahon hosted for six months during Clayton’s leave of absence for an illness.

The Barry – Enright produced shows ended in ’73, but six months later, the show was back on NBC as a Goodson – Todman syndicated production from the west coast with Jack Narz as host and ran till ’78. Art James was the original announcer. Enjoy and share!

July 2, 1964…President Johnson Signs Civil Rights Act Legislation

On July 2, 2014

- TV History

July 2, 1964…President Johnson Signs Civil Rights Act Legislation

This beautiful photo was taken in The East Room of The White House as President Johnson addressed the nation, just before signing The Civil Rights Act of 1964 into law.

For those of us who are old enough to remember these times, it’s interesting to recall the many famous faces in the front rows. If you take a look at the video clip (below) of this, it appears that there are three pool cameras from CBS covering the event. That center camera is shooting through a very early through the lens teleprompter. The blue part is actually the paper roll script with the black double mirror reflector box on top of it. -Bobby Ellerbee

The Secret To Voicing ‘Porky Pig’ In 30 Seconds…Amazing!

On July 2, 2014

- TV History

The Secret To Voicing ‘Porky Pig’ In 30 Seconds…Amazing!

Thanks to our friend Randy West, here is the current voice of ‘Porky Pig’, Bob Bergen unpacking the voice pattern that Mel Blanc perfected. Watching this is like learning to sing “The Name Game” by Shirley Ellis.

Porky Porky bo borky, banana fanna fo Forky, fe fi fo Forky, Porky!

For more on Bob, go to his Bio…http://www.bobbergen.com/bio.htm

Enjoy and share!

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=lXC_j5QB6v8

From the documentary, “I Know That Voice.” Bob Bergen, voice actor for “Looney Toons.” Mel Blanc was, without question, a genius. But this guy, the way he ha…

HAPPY BIRTHDAY…COMMERCIAL TELEVISION! 73 Today!

On July 1, 2014

- TV History

HAPPY BIRTHDAY…COMMERCIAL TELEVISION! 73 Today!

At 1PM, July 1, 1941, NBC’s WNBT in New York became America’s first commercially licensed television station to go on the air. At 2:30 PM, CBS owned WCBW became the second.

On June 24, 1941,both the NBC and CBS stations were licensed and instructed to sign on simultaneously on July 1 so that neither of the major broadcast companies could claim exclusively to be “first.”

However, WCBW did not manage to sign on the air until 2:30 p.m., one full ninety minutes after WNBT. As a result, WNBC inadvertently holds the distinction as the oldest continuously operating commercial television station in the United States, and also the only one ready to accept sponsors from its beginning.

The first program broadcast at 13:00 EST in the sign-on/opening ceremony featured the playing of “The Star Spangled Banner”, followed by an announcement of that day’s programs and the commencement of NBC television programming.

On its first day on the air, WNBT broadcast the world’s first official television advertisement before a baseball game between the Brooklyn Dodgers and Philadelphia Phillies. The announcement for Bulova watches, for which the company paid $9.00, displayed an NBC/RCA test pattern modified to look like a clock with the hands showing the time. The Bulova logo, with the phrase “Bulova Watch Time”, was shown in the lower right-hand quadrant of the test pattern while the second hand swept around the dial for one minute. Enjoy and share!

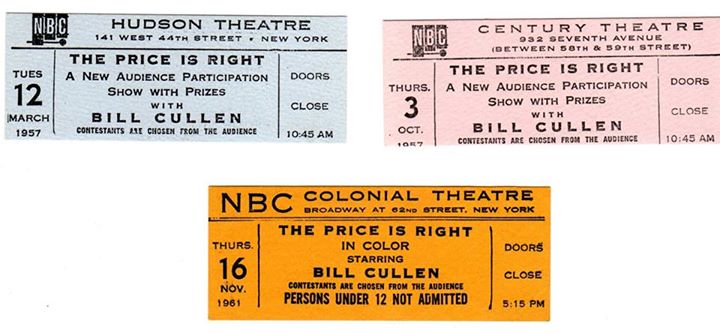

A New Can Of Worms…’The Price Is Right’ NBC Studio Locations

On July 1, 2014

- TV History

A New Can Of Worms…’The Price Is Right’ NBC Studio Locations

Frankly, I had always thought ‘The Price Is Right’ debuted in color from the Colonial Theater in 1956, but that is not quite right. It now appears the show (daytime) debuted from The Hudson Theater in black and white, however…the primetime version did debut from The Colonial, but that was in 1957. Here’s the rundown of dates and studios for the daytime show….

Hudson Theater 1956 – ’57 (b/w studio)

Century Theater 1957 – ’58 (b/w studio)

Colonial Theater 1959 (color studio)

Ziegfeld Theater 1960 (color studio)

Colonial Theater 1961 – 63 (color studio)

‘The Price Is Right’ prime time version always originated in color from The Colonial Theater from 1957- 63. The daytime show was in black and white from ’56 till ’62 and went color in it’s last year. Although the daytime show had come from NBC color facilities as early as 1959 and was usually shot with RCA TK41s, it was broadcast in b/w, which was not uncommon in the late 50s and early 60s. Thanks to David Schwartz for his help with this.

June 30,1952 …’The Guiding Light’ Debuted

On July 1, 2014

- TV History

June 30, 1952 is the day ‘The Guiding Light’ came to CBS television. It’s first TV home was in CBS Studio 56 at Liederkranz Hall on East 58th street, where two of the four studios there had Dumont cameras. After the consolidation of production into the CBS Broadcast Center and colorizing in the mid 60s, Liederkrantz was closed, but ‘TGL’ was a big show so CBS moved it to a facility of it’s own…Studio 65, The High Brown Theater on 26th Street, which had upstairs and downstairs studio floors.

The black and white photo is from September of ’52 in Studio 56. The two color photos are from Studio 65. The studio shot was taken in the basement and the control room and bigger studio were on the first floor. Occasionally, actors would have to race from one floor to the other to make appearances in the same scene.

‘The Guiding Light’ was created by Irna Phillips and began as an NBC Radio serial on January 25, 1937. On June 2, 1947, the series was moved to CBS Radio. Even after its television debut, the show would continue to be broadcast concomitantly on radio until June 29, 1956. The series was expanded from 15 minutes to a half-hour in early 1968, which is probably when the move from 56 to 65 occurred. The show expanded to a full hour on November 7, 1977. The series broadcast its 15,000th televised episode on September 6, 2006.

On April 1, 2009, it was announced that CBS had cancelled ‘Guiding Light’ after a 72-year run due to low ratings. The show taped its final scenes for CBS on August 11, 2009, and its final episode on the network aired on September 18, 2009. On October 5, 2009, CBS replaced Guiding Light with an hour-long revival of ‘Let’s Make a Deal’, hosted by Wayne Brady. ‘Guiding Light’ stands as the fourth longest-running program in all of broadcast history.

At the link is a full 15 minute episode from March 4, 1953 when the show as just 9 months old. The Duz commercial is live and the pitch man is the show’s announcer Hal Simms. The Ivory commercial appears to be on film. Thanks to Gady Reinhold for the color photos. Enjoy and share!

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=aTUMbA3SGt0

Here’s A Rare Sight & Great DGA Article…’I Love Lucy’

On June 30, 2014

- Archives, TV History

This is a fascinating article from Ted Elrick in “The Director’s Guild Of America Quarterly” on how the show was done. There is a lot of information there you won’t read anywhere else. The whole article is copied below.

http://www.dga.org/Craft/DGAQ/All-Articles/0307-July-2003/I-Love-Lucy.aspx

In the photo, we see Desi Arnaz with Jess Oppenheimer looking at a control booth under construction at General Services studio just before the show started production. This is probably around August of 1951.

Now this is really more of an audio and intercom center than anything else, because as you remember the show was shot on film, but coordination was still a key factor in the production. All the camera, dolly and boom people wore headphones. I would think there was an assistant director in the booth reminding them of cues and the DOP and director would be on the studio floor. Enjoy and share!

I Love Lucy

Directing the first multi-camera film sitcom before a live audience.

BY TED ELRICK

Desi Arnaz and Lucille Ball in I Love Lucy

On October 15, 1951, television broadcast history was made when the first episode of I Love Lucy aired on CBS. Technically, it was not the first episode of the show. The pilot, directed by Ralph Levy, was recorded as a kinescope, a 16mm filmed recording taken from an extremely bright cathode ray tube, but it was not broadcast until 1990. Kinescopes are fuzzy and often distorted, but were the only means for communities outside of the reach of coaxial cable linked network affiliates, predominately on the East Coast where most television programs originated, to see network programming. Lucy was the first multi-camera sitcom to be filmed before a live studio audience.

Its genesis was really something of a fluke, primarily driven by a cigarette manufacturer’s objection to kinescope films. When I interviewed him in the late 1970s, Desi Arnaz said that CBS and the show’s sponsor, Philip Morris, objected to making I Love Lucy in Los Angeles. The sponsor in particular didn’t want the lucrative New York and East Coast market, accustomed to quality broadcasts, seeing their show the way the rest of the country saw other shows, on kinescopes.

Lucille Ball and Desi Arnaz were adamant that this production stay in Los Angeles, where they had made their home for several years. A compromise to “film” Lucy was reached after the network’s complaints about the increased costs of shooting in that medium were offset by Arnaz and Ball agreeing to take a cut in their weekly salary. In return for this salary concession, CBS agreed that Arnaz and Ball would own the shows after they were broadcast. Both were truly surprised by CBS’ concession. That move alone would eventually make Desilu Productions one of the most powerful independent companies in television.

However, the problem remained of how to film the show. Many cinematographers said it was impossible to film multi-camera before a live audience. Different lighting requirements were needed for master shots, medium shots and close-ups. It just couldn’t be done. But that was not a phrase in Arnaz’ vocabulary.

He called veteran cinematographer Karl Freund, then in his early sixties, who told Arnaz the same, “It can’t be done.” According to Stefan Kanfer’s new book, Ball of Fire, The Tumultuous Life and Comic Art of Lucille Ball, Arnaz replied, “Well, I know that nobody has done it up to now, but I figured that if there was anybody in the world who could do it, it would be Karl Freund.” Needless to say, flattery got Arnaz everywhere, and Freund set to work, eventually accomplishing what couldn’t be done.

Film considerably raised the bar on broadcast quality. Suddenly, people across the country all saw the same image, and they liked it. I Love Lucy was a hit.

Live Audience and Directing

In his book, And the Show Goes On, television pioneer Sheldon Leonard wrote about another of Arnaz’ decisions: “Operating on the well-founded belief that a comedy show needs an audience to give it the authentic response that canned laughter can never duplicate, Desi brought in an audience to watch and react, while he used multiple-camera shooting technique borrowed from live TV.”

Arnaz also “borrowed from live TV” director Marc Daniels who would sit in the director’s chair for the filmed I Love Lucy. Daniels’ contribution to choreographing three-camera technique was considerable and influenced generations of television directors.

James Nicholson, William Asher and William Quine on the backlot at Columbia Pictures.

Daniels would direct all of the first season’s 35 episodes, a season uninterrupted by today’s all-too-common reruns. In the DGA Oral History, The Days of Live edited by Ira Skutch, Daniels said, “I’d had the multiple-camera experience. [Lucy] was similar to live, except that the film cameras were much less flexible than the television cameras. You were stuck with the side cameras being the long lenses for close-ups and the center camera being the master camera, and you couldn’t change a lens as quickly.

“We began I Love Lucy using four cameras because they wanted to do the entire first half of the show without stopping,” Daniels continued. “We had four Fearless dollies, four dolly grips, four camera assistants, two booms, two dolly grips for the booms, and a few cable men. You can imagine what that floor looked like.”

After the first season, Daniels moved on to direct other shows. William Asher, who would later produce 285 episodes, and direct 200 episodes himself of another television classic, Bewitched, came on board, becoming the directing mainstay for many years, and further refined and perfected multi-camera technique.

Trouble on Day One

Asher’s first day on the set though nearly ended his association with the show. They had begun rehearsal and Asher had to walk away for a bit to attend to some technical matters. When he returned, he discovered that Lucille Ball had been giving directions backstage. Asher was astonished.

“I said, ‘Lucy, there’s only one director. I’m it. If you would like to direct, then don’t pay me and send me home,’ ” Asher said. “When I said that, she began to cry and ran off the stage. Everybody disappeared. Desi hadn’t been in the scene. I didn’t know where to go because I had no office. So, I went to the men’s bathroom, sat on the toilet and didn’t know what the hell to do. I realized I’d blown my first day of what was really a pretty good job.

“I sat there for a long time and finally got up and went back to the stage,” he continued. “Desi was there. He was furious. He was cussing me out in Spanish and I didn’t know what he was saying. I settled him down and said, ‘Look, Desi, here’s what happened.’ And he said, ‘Well, you’re absolutely right, Bill. What you should do is go in to Lucy’s dressing room. She’s crying. Go talk to her and settle this thing.’ So that’s what I did. I went in. I said I was sorry I upset her. And she was crying and I started to cry. And after a while we went back to work. But I’ll tell you this. I never had trouble from her after that. She had her opinion, and would offer it, but nothing ever behind my back. Everything was just fine. That’s the way it was for the next five years.”

On the set of I Love Lucy with Lucille Ball and William Asher

Scripts, Rehearsals and Showtime Folks

Asher said they began working on each season of Lucy with between six and seven scripts that were in very good shape. “The scripts were excellent,” Asher recalled. “We had only the producer [and head writer], Jess Oppenheimer, and two other writers who wrote as a team [Madelyn Pugh and Bob Carroll, Jr.]. And that’s all we had. Today you see 9, 10, or more writers.” Oppenheimer, Pugh and Carroll had also been the writing team of Ball’s hit radio comedy My Favorite Husband. In Lucy’s later years Bob Schiller and Bob Weiskopf would write episodes.

Asher said there was very little ad libbing because the material was strong and they’d had time to rehearse. “On Monday morning we would read the material, discuss it and make changes. In the afternoon, I would start rehearsing and continue rehearsing Tuesday and Wednesday when the cameras came in. On Thursday, we’d rehearse again with cameras about half the day. Then we would do a dress rehearsal. Later that day, we’d do the show.”

Rehearsals were vital because they were shooting film. At the time there were no monitors for the director to see the image. The show’s quality depended on his ability to watch the floor and ensure that all cameras and actors hit their marks at the required moments. Precision was crucial, as nobody wanted to halt the performance in front of an audience. They rarely shot pick-ups, Asher said, and when they did it was usually for a guest star who forgot a line. Most shows were filmed in around thirty minutes.

“We had stops for Lucy’s big costume changes, but that was all,” Asher said. “I had a pretty strict rule on that. We didn’t stop for anything. We played it like a Broadway show. If an actor made a mistake or forgot a line or something like that, it was up to the other actor to get him out of it.”

(Top) Lucille Ball performs the famous “Vitameatvegamin” scene (Below) Lucille Ball, William Frawley, Vivian Vance and Desi Arnaz in a scene from I Love Lucy

Asher can recall only one time when the show came to a dead stop. “Lucy always had one moment where she’d get stuck. We’d put that line of dialogue on the back of a lamp or something where we knew she’d be working. Once, right in the middle of a scene she suddenly stopped. And she was the only one in the scene, alone in the living room. I waited and waited. She just was staring at something. Finally, I yelled ‘cut’ and ran down to the set and saw she was staring at the back of a lamp where we’d put her line. She said the line didn’t seem right to her. It turned out that the lamp we were using in that show broke after dress rehearsal, and the crew brought in another lamp that had a line from a previous show from the year before on it. We explained it to the audience and replaced it with the right line and went on. It was the only time we stopped.”

Yet Another Innovation

On Friday, Asher would cut the show with the editor, and on Monday, during lunch following the next show’s read through, he’d watch the prior week’s show with Arnaz who would give his comments.

The editing of I Love Lucy brought another major innovation to television. Arnaz said that when he first sat down to watch the film, he found it very confusing to look at only one camera’s footage on a Moviola. He asked why he couldn’t see the film from all three cameras at the same time. He was told that this was the only way — one camera’s film at a time. Arnaz pushed the issue and asked, “Why can’t you just stick three Moviolas together?” So the production team contacted Moviola’s president, Mark Serrurier, son of Iwan Serrurier who had created Moviola in 1924. A graduate of Caltech who oversaw the design of the dome and structural parts of the 200-inch Palomar Telescope, Serrurier developed a three-headed machine to speed up the editing process on Lucy.

Jay Sandrich, who would establish his own directing legacy on The Mary Tyler Moore Show, Soap and The Cosby Show, began his career as a 2nd AD on I Love Lucy. He moved up to 1st AD when Jack Aldworth moved up to producer. “I was 24 and I knew nothing,” Sandrich said. “I was learning on the number one show in the country. Aldworth was a wonderful mentor who really helped me.”

After thousands of reruns in syndication, it’s sometimes easy to forget just how innovative I Love Lucy was to the history of sitcoms. But it set the stage for further technical innovations, for influential independent producers like Sheldon Leonard, Norman Lear, and Grant Tinker, and for strong directors whose voice and commitment to the idea that “There can be only one director” would continue to perfect the uniquely American art form known as the sitcom.

Johnny Carson Desk…Sold for $35,000

On June 30, 2014

- TV History

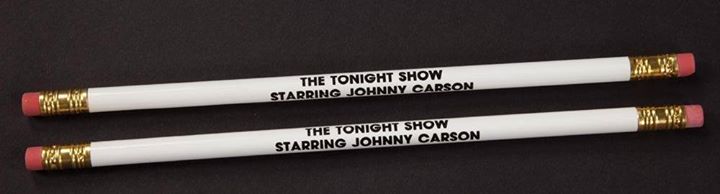

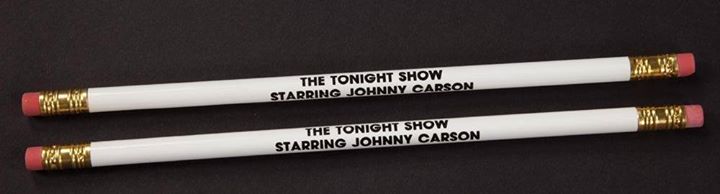

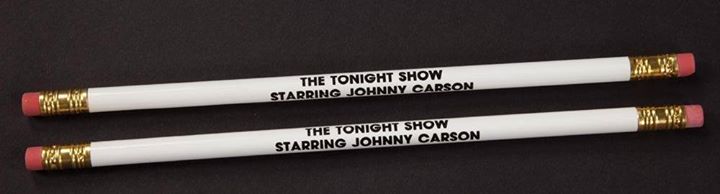

Johnny Carson Desk…Sold for $35,000 (Click Images To Enlarge)

In October of 2005, this Carson desk sold at auction for $35,000. It was one of around five different desks used on the show and as mentioned on the photo was thought to have been on the set from 1974 till 1981. Here is the auction description…

“The top has a gold formica finish. The inside is carpeted in shag with a “hidden” slide-out tray on which Carson placed his ashtray so it would not be seen by the television audience once it became unfashionable to smoke on the air. This vertically grained rosewood finish desk is really not very large — approximately 60″ x 31″ x 21″

The two pencils shown here were also auctioned but I don’t know what they went for. These were specially made for the show and had erasers on both ends so Johnny could drum along with the band at his desk more easily.

The Very First Hanna – Barbera Cartoon…’Ruff & Ready’

On June 30, 2014

- TV History

The Very First Hanna – Barbera Cartoon…’Ruff & Ready’

This is the very first episode of ‘Ruff & Ready’. It aired on NBC December 14, 1957 and was the first cartoon ever produced by Bill Hanna and Joe Barbera’s new company.

Ruff (the cat) was voiced by Don Messick, and Reddy was voiced by Daws Butler. Messick also narrated.

New Mexico native William Hanna and New York City born Joseph Barbera first teamed together while working at the Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer cartoon studio in 1939. Their first directorial project was a cartoon entitled ‘Puss Gets the Boot’ (1940), which served as the genesis of the popular ‘Tom and Jerry’ series of cartoon theatricals.

Hanna and Barbera served as the directors and story men for the shorts for eighteen years. Seven cartoons of the series won seven Oscars between 1943 and 1953. In 1955, Hanna and Barbera became the producers in charge of the MGM animation studio’s output. Outside of their work on the MGM shorts, the two men moonlighted on outside projects, including the original title sequences and commercials for ‘I Love Lucy’.

MGM decided in early 1957 to close its cartoon studio. Hanna and Barbera, contemplating their future while completing the final ‘Tom and Jerry’ and ‘Droopy’ cartoons, began producing animated television commercials.

During their last year at MGM, they developed a concept for an animated television program about a dog and cat pair who found themselves in various misadventures. After they failed to convince MGM to back their venture, live-action director George Sidney, who’d worked with Hanna and Barbera on several of his features – most notably Anchors Aweigh in 1945 – offered to serve as their business partner and convinced Screen Gems, the television subsidiary of Columbia Pictures, to make a deal with the animation producers. Screen Gems took a twenty percent ownership in Hanna and Barbera’s new company, H-B Enterprises, and provided working capital. H-B Enterprises opened for business in rented offices on the lot of Kling Studios (formerly Charlie Chaplin Studios) on July 7, 1957, two months after the MGM animation studio closed down. The rest, as they say, is history! Enjoy and share!

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=zQKU9ChKUFU

Visit www.cartoons-forum.org to get retro cartoons of many cartoon studios,such as Disney,Hanna-Barbera,Ruby-Spears,Filmation, etc. You can also be part of o…

Behind The Scenes Of ‘Wonderama’…WNEW

On June 30, 2014

- TV History

Behind The Scenes Of ‘Wonderama’…WNEW

This 6 minute clip takes us into the control room with Sonny Fox as our host some time in the early 60s. From 1944 till 1958 this was WABD, Dumont’s flagship station in New York, but in ’58 it became WNEW. There is classic Dumont TV equipment everywhere.

‘Wonderama’ was a popular children’s program that ran for three hours on Sunday mornings on the Metromedia-owned stations from 1955 to 1986, Besides NYC, it ran in five other markets…WTTG in Washington D.C., KMBC-TV in Kansas City, KTTV in Los Angeles, WXIX-TV in Cincinnati, and WTCN-TV in Minneapolis – Saint Paul.

In February of ’55, the Dumont network shut down, but their TV stations continued as independents. In May 1958, DuMont Broadcasting changed its name to the Metropolitan Broadcasting Corporation in an effort to distinguish itself from its former corporate parent and the corporate name change to Metromedia came in 1961. Enjoy and share!

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=wfo5wCwai2Q

Sonny takes his young viewers into the control room of his Sunday morning WNEW-TV program to see how a television show is made. Check out the 1950s DuMont br…

The Very First “Made For Television” Cartoon…’Crusader Rabbit’

On June 30, 2014

- TV History

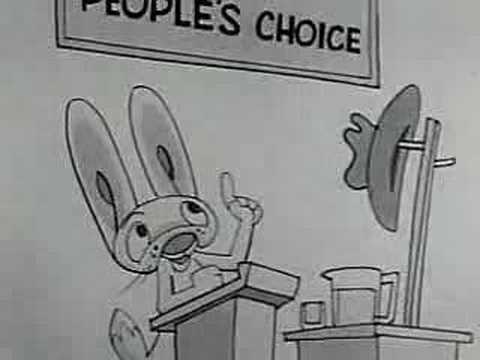

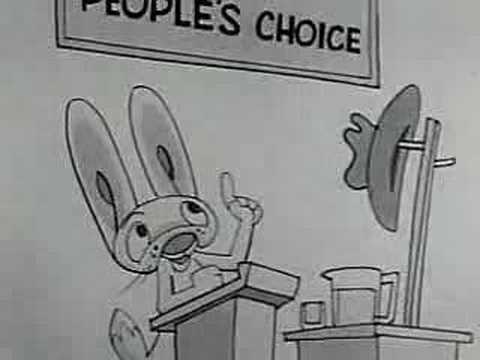

The Very First “Made For Television” Cartoon…’Crusader Rabbit’

The concept of an animated series made for television came from animator Alex Anderson, who worked for Terrytoons Studios. Terrytoons turned down Anderson’s proposed series, preferring to remain in theatrical film animation, which opened the door for him to team up with Jay Ward.

The main difference between producing cartoons for movie audiences vs television audiences is money, effort and volume. Since television eats creative effort a lot faster, more episodes have to be done but for financial and production reasons, shortcuts have to be taken for television animation.

In a 20 second clip, a theatrical cartoon could require anywhere from 700 to 1000 drawings. These first cartoons made for television used only about 250 to 300 drawings per 20 seconds. To help with the lack of movement, a narrator was used.

In early 1947, Anderson approached Jay Ward to create a partnership—Anderson being in charge of production and Ward arranging financing. Ward became business manager and producer, joining with Anderson to form “Television Arts Productions” in 1947.

They tried to sell the series to the NBC television network, but the network did not go with it. Although NBC did not telecast ‘Crusader Rabbit’ on their network, it did buy the show for it’s owned and operated stations and allowed the series to be nationally syndicated.

Below is the first episode of ‘Crusader Rabbit’ which made it’s television debut on September 1, 1949 on KNBH in Hollywood. WNBC-TV in New York continued to show the original Crusader Rabbit episodes from 1949 through 1967, and some stations used the program as late as the 1970. Enjoy and share!

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=C3hHQvkUhJo

Jay Ward’s Crusader Rabbit – Crusade 1 / Episode 1. Like to see more?

Fans Of Animation Will Love This Page! Rare Early Cartoons…

On June 30, 2014

- TV History

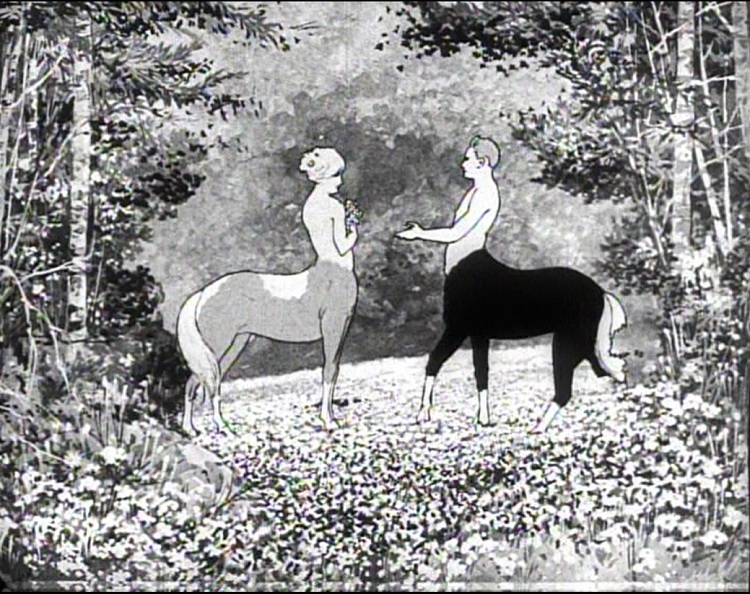

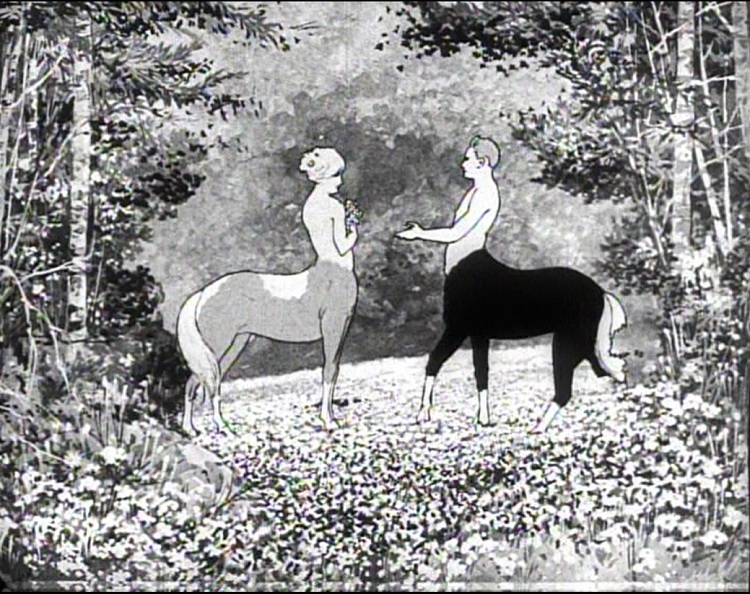

Fans Of Animation Will Love This Page! Rare Early Cartoons…

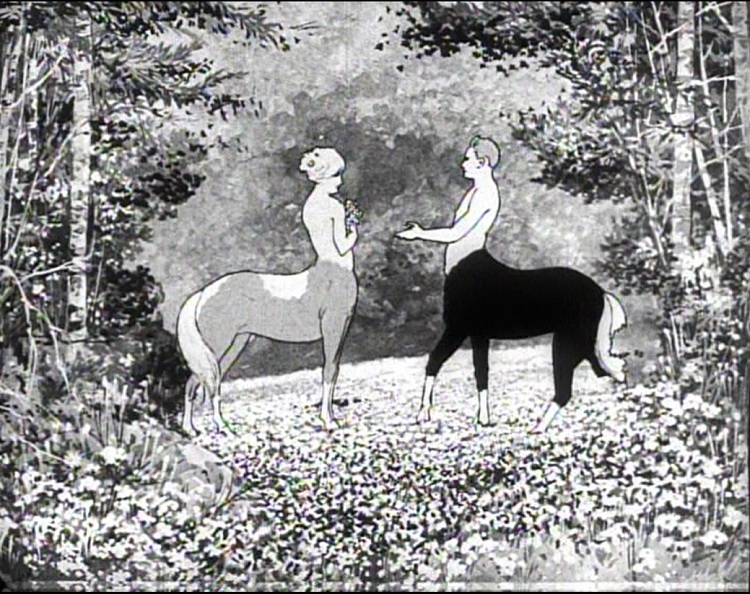

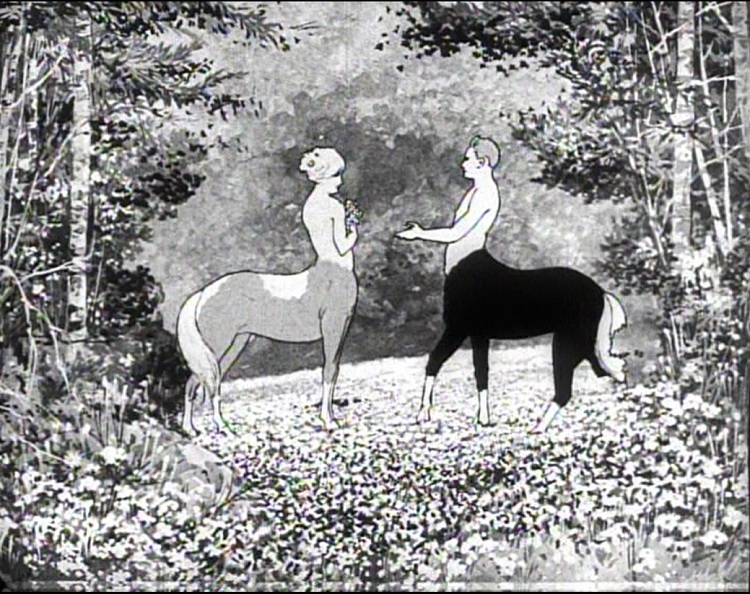

The link will take you to a Library Of Congress page that features restored early animation. Here, you can see some of the first claymation stop motion, the first rotoscope films of Max Fleischer’s ‘Koko The Clown’ which combines live action and animation, and more. The clip here is two minute fragment from 1921 of ‘The Centaurs’, which is notable for it’s particular quality of line and movement way ahead of its time…done twenty years before Disney would reach such heights with Fantasia. Enjoy and share!

http://publicdomainreview.org/collections/the-centaurs-a-fragment-1921/

The Centaurs, a Fragment (1921)

The only surviving fragment of Winsor McCay’s now lost The Centaurs, produced in 1921 by Rialto Productions.

Page 73 of 136

« Previous

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

30

31

32

33

34

35

36

37

38

39

40

41

42

43

44

45

46

47

48

49

50

51

52

53

54

55

56

57

58

59

60

61

62

63

64

65

66

67

68

69

70

71

72

73

74

75

76

77

78

79

80

81

82

83

84

85

86

87

88

89

90

91

92

93

94

95

96

97

98

99

100

101

102

103

104

105

106

107

108

109

110

111

112

113

114

115

116

117

118

119

120

121

122

123

124

125

126

127

128

129

130

131

132

133

134

135

136

Next »